EDITOR’S NOTE: This essay is reprinted here with the gracious permission of City Journal, who first published it in the Summer 2007 issue of their magazine.

Mozart’s lighthearted opera The Abduction from the Seraglio does not call for a prostitute’s nipples to be sliced off and presented to the lead soprano. Nor does it include masturbation, urination as foreplay, or forced oral sex. Europe’s new breed of opera directors, however, know better than Mozart what an opera should contain. So not only does the Abduction at Berlin’s Komische Oper feature the aforementioned activities; it also replaces Mozart’s graceful ending with a Quentin Tarantino-esque bloodbath and the promise of future perversion.

Welcome to Regietheater (German for “director’s theater”), the style of opera direction now prevalent in Europe. Regietheater embodies the belief that a director’s interpretation of an opera is as important as what the composer intended, if not more so. By an odd coincidence, many cutting-edge directors working in Europe today just happen to discover the identical lode of sex, violence, and opportunity for hackneyed political “critique” in operas ranging from the early Baroque era to that of late Romanticism.

Until now, New York’s Metropolitan Opera has stood resolutely against Regietheater decadence. In fact, its greatest gift to the world at the present moment is to mount productions – whether sleekly abstract or richly realistic – that allow the beauty of some of the most powerful music ever written to shine forth.

The question now is whether that musical gift will continue.

The Met’s new general manager, Peter Gelb, hit Lincoln Center last year like a comet, promising to attract new audiences by injecting more “theatrical excitement” into the house. Predicting what that would ultimately mean was difficult enough before another bombshell exploded this February: New York City Opera, the smaller company across the plaza from the Met, announced that it had hired Europe’s most prominent exponent of Regietheater as its next general manager. The shock waves at Lincoln Center still reverberate.

This time of critical transition is an opportune moment both to celebrate the Met’s role in preserving a central glory of Western culture, and to consider the great opera house’s future. To see how much is at stake, one need only glance across the Atlantic and, increasingly, at other opera companies here in the United States.

The reign of Regietheater in Europe is one of the most depressing artistic developments of our time; it suggests a culture that cannot tolerate its own legacy of beauty and nobility. Singers, orchestra members, and conductors know how shameful the most self-indulgent opera productions are, and yet they are powerless to stop them. Buoyed with government subsidies, and maintained by an informal alliance of government-appointed arts bureaucrats and critics, the phenomenon thrives, even when audiences stay away in disgust.

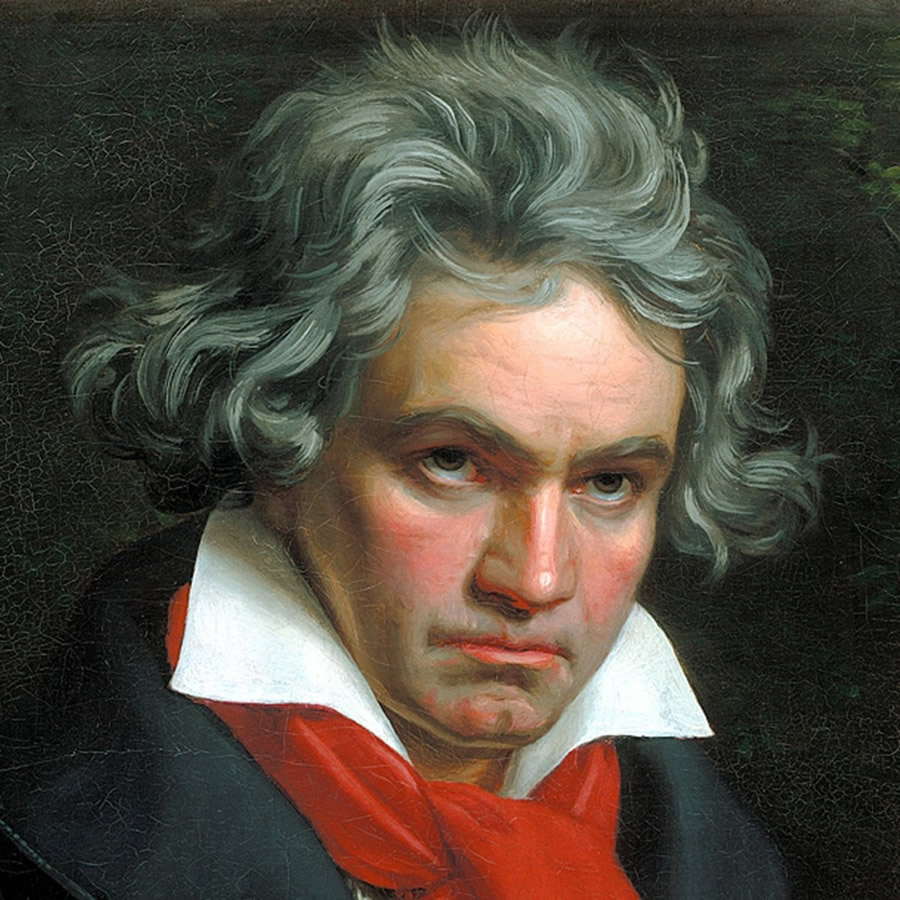

The injury that Regietheater does to Mozart, Handel, and other benefactors of humanity is heartbreaking enough. But it also hurts the public, by denying new audiences the unimpeded experience of an art form of unparalleled sublimity. The seventeenth-century Florentines who created the first operas sought to recover the power of Greek tragedy, which united drama and song. Since then, opera has expressed a limitless range of human emotions, set to music of sometimes unbearable exquisiteness. Initially devoted to the exploits of kings and gods, opera by the end of the nineteenth century had conferred on the passions of workers and shopkeepers an equal grandeur, worthy of the majestic resources of the symphony orchestra.

The trajectory of the Komische Oper’s Abduction from the Seraglio – from the object of an in-house revolt to a sold-out triumph – is a fitting introduction to the decadence of Europe’s present musical culture. The episode presents a depressing variant on Mel Brooks’s The Producers: whereas Max Bialystok knew that his Springtime for Hitler was garbage and expected failure, the director of thisAbduction, Calixto Bieito, assumed that his travesty would be a success – and it was.

Bieito is the most offensive director working in Europe today. Accordingly, he is in high demand; he has mauled Verdi, Puccini, Mozart, and Richard Strauss in London, Copenhagen, Barcelona, Hanover, and numerous other venues. Like many Regietheater directors, the Catalan Bieito piously claims to take his cues from the music itself. “I think I am very loyal to Mozart,” he notes. “There is nothing more to say.”

Actually, there is a lot more to say. The Abduction from the Seraglio is a humorous tale of the capture of a group of Europeans by a Turkish pasha, who tries to win the love of one of them; Mozart lavishes joyful, driving rhythms – led by piccolo, triangle, and cymbals – on its Turkish themes, and adds a rich lode of elegant solos, particularly for tenor. Bieito transferred the Abduction to a contemporary Eastern European brothel and translated the dignified pasha of Mozart’s sadly irrelevant tale into the brothel’s sick pimp overseer. To give the production’s explicit sadomasochistic sex an even greater frisson of realism, Bieito hired real prostitutes off the streets of Berlin to perform onstage. Needless to say, neither the streetwalkers nor the whippings, masturbation, and transvestite bondage are anywhere suggested in Mozart’s opera. In one representative moment, the leading soprano, Constanze – who has already suffered digital violation during a poignant lament – is beaten and then held down and forced to watch as the pasha’s servant, Osmin, first forces a prostitute to perform fellatio on him and then gags the prostitute and slashes her to death. Osmin hands the prostitute’s trophy nipples to Constanze, who by then is retching.

The episode perfectly illustrates the opportunistic literalism typical of culturally ignorant – and musically deaf – contemporary directors. It takes place as Constanze is singing one of the most difficult arias in the soprano literature, “Martern aller Arten” (“Tortures of Every Kind”). “Martern” is an obstacle course of leaps and trills accompanied by melting winds and propulsive harmonies, all meant to convey Constanze’s nobility in refusing the pasha’s demands for her love. It belongs in the long literary tradition of tragic rhetoric; its mention of torture is not a stage direction. Mozart immediately follows the number with a buoyant aria by Constanze’s maid and a return to the lightest farce – making clear that nothing untoward has happened to Constanze or to anyone else in the opera. But Bieito seizes on the torture reference, stripped of its musical and dramatic context, to justify his pornographic mayhem.

Like all Regietheater directors, Bieito has little tolerance for happy endings – or for any set of values at odds with his own clichéd worldview. In the conclusion to Mozart’s opera, the four European captives sing a hymn of praise to the pasha for granting them liberty and for renouncing revenge for a cruelty done to the pasha by a captive’s father long ago. Such celebrations of enlightened rule, even by a Muslim, were standard in Baroque and Classical operas; there is no reason to think that Mozart didn’t fully embrace the sentiments behind the convention.

Bieito doesn’t, however. In the finale of his Abduction, after a gruesome massacre of the writhing prostitutes, Constanze shoots first the pasha and then herself. So the concluding chorus of “long live the pasha” is mystifyingly directed at a dead man. No matter. Better to make nonsense of Mozart’s libretto than to allow such outdated sentiments as forgiveness, gratitude, and nobility to show up on an opera stage.

The orgies and boorish behavior that Bieito demands of his characters do violence to the music above all, so it was fitting that the Komische Oper’s orchestra members were the first to rebel. The musicians nearly mutinied during rehearsals for the 2004 premiere, according to the online magazine Klassik in Berlin, and backed down from a threatened walkout only after angry negotiations with Bieito and the musical director. Opera staff observing a late rehearsal stormed out of the house, and a palpable depression settled over the chorus. “Such a thing does not deserve to be seen on our stage… on any stage,” one chorus member said. The opening-night audience shared the musicians’ dismay. “Mozart didn’t intend this!” shouted protesters. But audience sentiment has little purchase in Europe’s subsidized opera houses. At the cast party after the premiere, Berlin’s top corporate and political leaders rubbed shoulders with strippers and whores, resulting in one of the most scintillating events in years, reported Klassik in Berlin.

Then a DaimlerChrysler official said that he didn’t think that the company should support such work with its grant money, guaranteeing the production’s success by conferring on it the exalted status of victim of corporate censorship. (Private support for Berlin’s three opera houses is still marginal compared with government funding, though.) Defending the importance of Bieito’s production, Berlin’s culture senator – a bureaucrat who dispenses government arts subsidies – argued that its “description of blood, sex, and violence is a true reflection of social phenomena.” Perhaps the senator was unaware that there are no such “social phenomena” in Mozart’s Abduction. Or perhaps it no longer matters.

DaimlerChrysler, facing a public-relations fiasco, recanted penitently. The production sold out for the remainder of its run and has been twice revived. Any first-time listener who came away with the slightest intimation of the charm of Mozart’s Singspiel must have had an extraordinary ability to rise above squalor in pursuit of the sublime.

Other Regietheater directors may not yet have achieved the sheer volume of gratuitous perversion and bloodletting that Bieito managed to cram into his Abduction – but their aesthetic obeys the same impulse. Gérard Mortier, City Opera’s incoming general manager and the current head of the Paris Opera, staged a Fledermaus at the Salzburg Festival that dragooned Johann Strauss’s delightful confection into service as a cocaine-, violence-, and sex-drenched left-wing “critique” of contemporary Austrian politics. An American tenor working in Germany remembers another Fledermaus with a large pink vagina in the center of the stage into which the singers dived. The innocent sea captain’s daughter, Senta, in the Vienna State Opera’s Flying Dutchman has posters of Che and Martin Luther King in her bedroom instead of a picture of the mysterious Dutchman, and burns herself to death with gasoline rather than jumping into the sea to meet her phantom beloved. Don Giovanni is almost invariably an offensive slob who masturbates and stuffs himself with junk food and drugs, surrounded by equally repellent psychotics, perverts, and sluts. (Operagoers can thank American director Peter Sellars for this tired convention.) Handel’s Romans and nobles come accessorized with machine guns, sunglasses, and video cameras, while jerking like rappers to delicate Baroque melodies.

The world at large got a glimpse of Regietheater last year, thanks to the furor over the Deutsche Oper Berlin’s Idomeneo; unfortunately, the controversy focused on the wrong issue. The real outrage was not that the company considered canceling the show for fear of a Muslim backlash but that the potential provocation of that backlash – Mohammed’s severed head perched jauntily on a straight-backed chair – had absolutely nothing to do with Mozart’s opera. Director Hans Neuenfels had injected Mohammed’s and other religious figures’ heads into the classical Greek story simply to register his personal dislike of religion. Neuenfels’s next project: a Magic Flute with a large penis for the flute.

The list of tone-deaf self-indulgences could be extended indefinitely. Their trashy sex and disjunctive settings are just the symptom, however, of a deeper malady. The most insidious problem with Regietheater is the directors’ hatred of Enlightenment values. Where a composer writes lightness and joy, they find a “subtext” of darkness. A recent modernized version of The Marriage of Figaro at the Salzburg Festival showed Figaro angrily slashing the page Cherubino’s arm and smearing him with blood during the jaunty aria “Non più andrai.” That aria, in which Figaro teases the young dandy about his upcoming banishment to the army, is gently mocking, not dark and violent. But in a transgressive director’s hands, humor, reconciliation, happiness, and above all else, grandeur must be exposed as mere fronts for despair, resentment, and the basest instincts. No positive sentiment can appear without a heavy overlay of irony.

Just because our age regards grand ideals with cynicism, however, that does not license us to write them out of the great works of the past. Doing so only impoverishes us. “There is considerable intellectual laziness in the idea that the past must be problematized and that older works must be ‘rescued’ from their ideological presuppositions,” says New Yorker critic Alex Ross. “Looking at the extraordinary mess the world is in, you might suppose that it’s our ideological presuppositions that are inherently flawed, and that we can actually draw useful moral lessons from the past.”

Regietheater directors undoubtedly think of themselves as sophisticated when they unmask courtly decorum as just a cover for fornication. The demystifiers’ awareness of desire is so crude that they cannot hear that the barely perceptible darkening of a voice or the constricted suffusion of breath into a note can be a thousand times more erotic than a frenzy of pelvic thrustings. And they rage against aesthetic conventions whose complexity challenges their simplistic understanding of human experience. Peter Sellars created one of Regietheater’s most horrifying images in his production of The Marriage of Figaro, set in Trump Tower: Cherubino, clad in hockey uniform, humping a mattress like a crazed poodle during the breathless aria “Non so più cosa son.” In the aria, Cherubino sings of his confusion in the presence of women and his compulsion to speak about love – “waking, dreaming, to water, to shadows, to the mountains.” “I know, it’s all just about sex!” giggles Sellars, like some 12-year-old with his first Playboy. Well, no, actually, it’s not. This sexual dumb show is inimical to the delicacy and innocence of the aria, whose beauty consists in part of sublimating desire into the artifice of pastoral poetry. Sellars’s staging belongs with a Snoop Dogg rap rant, not with Mozart and his librettist, Lorenzo da Ponte.

Europe is cursed with critics just as musically insensate and aesthetically illiterate as the directors whom they promote. Lydia Steier of Klassik in Berlin applauded the Bieito Abduction for “cut[ting] through any sentimental membrane protecting the opera from the stomach-churning brutality of such modern phenomena as human trafficking and snuff films.” This statement may well be the stupidest ever offered in defense of Regietheater. There is no “sentimental membrane” protecting Mozart from snuff films; there is not even the remotest connection between the two. The Guardian’s opera reviewer, Charlotte Higgins, was mystified that Bieito’s production of Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera at the English National Opera garnered “furious headlines.” By Higgins’s own account, it contained the usual “transvestites, masturbation, simulated sex, nudity and, in the opening scene, a row of men sitting on toilets.” So what’s the big deal? asked Higgins. “The fact that you can get all that and more on TV every night seemed not to deter the carpers, presumably because opera is supposed to be respectable,” she sneered. But serious operagoers aren’t protesting transvestites or masturbation per se, only the minor detail that they have nothing to do with the sound world of Verdi.

Singers generally detest transgressive productions, but have little clout. No one wants to acquire a reputation for being obstructionist. Even the great American baritone Sherrill Milnes felt that he had to compromise on an outrageous demand during a German production of Verdi’s Otello. During the third-act duet in which Otello accuses Desdemona of being a whore, a “well-known stage director,” as Milnes describes him, wanted Milnes’s Iago to crawl on his belly across the stage. And then, says Milnes, “he wanted me to jerk off and have an orgasm.”

Milnes was astounded. “I won’t do it, it’s wrong on every front,” he remembers responding. “At the very least, it’s rude to interrupt the focal point of the scene between Desdemona and Otello. It’s not about Iago’s reaction.” (In fact, Iago is not even supposed to be onstage.) “No way I’ll put my hand on my crotch; it’s embarrassing for Sherrill Milnes and it’s embarrassing for Sherrill Milnes as Iago.” But Milnes gave ground: “I came on the stage, but not as long as the director wanted, breathed a little hard and exited.”

A few singers have walked out on productions, but more often they grit their teeth and just try to get through them. Diana Damrau, a rapidly rising German soprano, draws herself up with icy haughtiness when asked about her participation in the infamous Bavarian State Opera Rigoletto, set on the Planet of the Apes. “I fulfilled my contract,” she says scornfully. “This was superficial rubbish. You try to prepare yourself for a production, you read secondary literature and mythology. Here, we had to watch Star Wars movies and different versions of The Planet of the Apes…. This was just…noise.”

Well into the twentieth century, conductors controlled opera staging, and in theory they could still beat back Regietheater today. But they, no less than singers, worry about jeopardizing their careers. “You need courage to oppose it,” says Pinchas Steinberg, former chief conductor of the Vienna Radio Symphony and former principal guest conductor of the Vienna State Opera. “People start to say: ‘You can’t work with this guy, he creates problems.’” Conductor Yuri Temirkanov did quit a production of Tchaikovsky’s Queen of Spades at the Opéra de Lyon in 2003. “I wouldn’t be able to live with my conscience if I conducted that [garbage],” he told the general director. Such showdowns are rare, however.

That leaves the audience as the final bulwark against the trashing of opera. But even when audiences stay away in droves – and “sometimes in those productions you could shoot ducks in the auditorium and not hit anyone,” says Milnes – the managerial commitment to Regietheater usually remains firm.

None of the conventional explanations for the rise of Regietheater in opera is fully convincing. Certainly the prevalence of massive state subsidies allows European opera managers to shrug off paltry box-office numbers. And to justify those subsidies, opera houses currently feel compelled to prove that they are not “elitist” institutions, observes Alex Ross. “Alleged critiques of the bourgeois order, the conservative establishment, etc. fit the bill.”

But while subsidies may be a necessary condition for Regietheater, they are not a sufficient one. European opera has been subsidized to varying degrees throughout its centuries-long history without generating the musical abuse that is now so common. And Regietheater productions are creeping into the US, where opera relies overwhelmingly on private support. The Spoleto Festival USA, for example, has presented the usual masturbating Don Giovanni; a recent Rossini Cenerentola (Cinderella) in Philadelphia featured a motorcycle and large TV screens projecting the characters’ supposed thoughts; City Opera mounted a Traviata in the 1990s that ended in an AIDS ward. Manager Pamela Rosenberg tried to make the San Francisco Opera a premier venue for European-style directing in the early 2000s, but she is gone now, after losing thousands of subscribers. The market provided the necessary corrective in San Francisco, but other managers, seeking elite acclaim, will make similar attempts in the future.

Germany’s postwar reaction to Nazism also undoubtedly contributed to the emergence of transgressive stagings there in the 1970s, yet more as a pretext than as an actual cause. The most radical reaction to Nazism in the opera world to date had nothing to do with today’s trashing impulse. When the Bayreuth Festival, Richard Wagner’s shrine, reopened in 1951, Wagner’s grandson, Wieland Wagner, discarded Richard’s own naturalistic sets and replaced them with light alone. Jettisoning Richard Wagner’s picturesque realism, which had come to be associated with National Socialism, was revolutionary, but it did not arise from any assumption on Wieland’s part that he was licensed to “deconstruct” his grandfather’s works. Today’s bad boys of German opera may puff themselves up with the belief that they are contributing to denazification, but nothing in that project compels their aesthetic choices. Nor does anti-Nazism explain the attraction of Regietheater outside Germany.

The current transgressive style of opera production is better understood as a manifestation of the triumph of adolescent culture, which began with the violent student movement of the 1960s. Even as West Germany forged ahead economically, its intellectuals, students, and artists became infatuated with the prosperity-killing Marxism practiced in stumbling East Germany. West German opera houses began inviting East Berlin directors to bring their heavy-handed critiques of capitalism, staged on the backs of Wagner and other composers, to Western venues. The situation was the same across Europe. “Student dissatisfaction with materialism… echoed in the theaters, notably in repertory and styles of production that were critical of bourgeois values and the status quo,” writes Patrick Carnegy in Wagner and the Art of the Theatre. In Paris in the late 1960s, City Opera manager-in-waiting Gérard Mortier led a group of student provocateurs who loudly disrupted opera productions that they considered too traditional.

The defining characteristic of the sixties generation and its cultural progeny is solipsism. Convinced of their superior moral understanding, and commanding wealth never before available to average teenagers and young adults, the baby boomers decided that the world revolved around them. They forged an adolescent aesthetic – one that held that the wisdom of the past could not possibly live up to their own insights – and have never outgrown it. In an opera house, that outlook requires that works of the past be twisted to mirror our far more interesting selves back to ourselves. Michael Gielen, the most influential proponent of Regietheater and head of the Frankfurt Opera in the late seventies and eighties, declared that “what Handel wanted” in his operas was irrelevant; more important was “what interests us… what we want.”

Nicholas Payne, former general director of the English National Opera and champion of Calixto Bieito, echoes this devaluing of the past. “Director’s theater or whatever you want to call it is an attempt to grab the material and make it speak to the spirit of today’s times, isn’t it?” he says. “I’m not saying that the only way to do [Monteverdi’s] Poppea is to make Nero the son of the chief guy in North Korea. Nevertheless, if you’re bothering to reproduce Poppea, it has to have some way of speaking to people now.” It’s hard to know whom that statement insults more – contemporary audiences or Monteverdi. Payne assumes that Monteverdi’s works are so musically and dramatically limited that they cannot speak to us today on their own terms, and that audiences so lack imagination that they cannot find meaning in something not literally about them.

The dirty little secret of Regietheater is this: its practitioners know that no one will bother to show up for their drearily conventional political cant unless they ride parasitically on the backs of geniuses. Bieito has said that his purpose in staging The Abduction from the Seraglio was to highlight abuses in the contemporary sex trade. Let’s pretend for a moment that Bieito actually cares about the fate of “sex workers.” His path is clear: keep his grubby mitts off Mozart and write his own damn opera. But without Mozart or Verdi, the Regietheater director is nothing; he cannot even hope for third-rate avant-garde status. In a world where displaying bodily fluids in jars, performing sex acts in public, or trampling religious symbols will land you a gig at the Venice Biennale and a government grant, the only source of outrage still available to the would-be scourge of propriety is to desecrate great works of art.

Occasionally, Regietheater proponents admit to their aspirations to shock. More often, however, they package themselves as the saviors of art. Gérard Mortier says that in updating operas, he seeks to “transform a work dated in a certain era so it communicates something fresh today.” He has it exactly backward. There is nothing less “fresh” than the tired rock-video iconography, the consumer detritus of beer cans and burgers, or the anti-imperialist, anti-sexist messages that Regietheater directors graft on to operas to make them “relevant.” What is actually “fresh” about a Mozart opera, besides its terrible beauty, is that it comes from a world that no longer exists. And it is, above all, the music that bodies forth that difference. The Baroque and Classical styles in particular convey an entire mode of being, one that values grace and artifice over supposed authenticity and untrammeled self-expression.

Regietheater directors are infallibly deaf to the dramatic imperatives in the music that they stage. Bieito says that he hears in Don Giovanni, that work of unbearable grandeur, the “nihilism of the modern world” – a confession that should have disqualified him even from buying an opera CD. Nicholas Payne, who brought Bieito’s Don Giovanni to the English National Opera, says that he is particularly fond of the moment in the Bieito production when Don Giovanni sings his canzonetta to Donna Elvira’s maid, “Deh, vieni alla finestra,” into a phone, instead of serenading her underneath her window with his mandolin. “There’s something a little bit twee about getting out that lute, isn’t there?” Payne asks. Suggestion to directors: if the troubadour tradition embarrasses you, you should not be in the business of producing opera.

The real problem with Payne’s admiration for Bieito’s canzonetta setting, however, is that it completely misjudges the music. Bieito makes the scene yet another depressing episode in the “nihilism of the modern world”: Don Giovanni is sitting alone in an empty bar strewn with the refuse of heavy partying. After singing the serenade, weighed down with despair, he drops the phone – there is no indication that anyone is on the other end – and lays his head on the table in front of him. This tableau has nothing to do with the music or text. The sinuous “Deh, vieni alla finestra,” far from being a moment of morbid paralysis, is the very emblem of the Don’s irrepressible will. Though he has recently been caught out and denounced as a hell-bound libertine by his fellow nobles, he is happily back at his conquests, pouring seductive power into the crescendos of the canzonetta. Bieito’s listless Giovanni could not possibly sing the music that Mozart has given him.

Jonathan Miller seethes with contempt for American audiences in general and the Metropolitan Opera in particular, which he accuses of mounting “kitschy” and “vulgar” productions. Yet at New York City Opera this season, he set Donizetti’s pastoral comedy L’Elisir d’Amore in a 1950s American diner, complete with gum-chewing Elvis fans and Jimmy Dean iconography – as hackneyed a set of visuals as any in the Regietheater director’s puny bag of tricks. Asked if Donizetti’s poignant melodies really match the sock-hop antics on stage, Miller responds defensively: “The music works perfectly well with my setting; it’s a witty transformation, that’s all. It’s as good as those staid pieces of rusticity which satisfy Met audiences because they want sedentary tourism.” But doesn’t music provide a check on how a work can be staged? “Music doesn’t have any checks in it,” he insists. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Moreover, when directors yank operas out of their historical contexts, they close a precious window into the past. Most operas’ assumptions about nobility, virtue, and the duties of rulers and subjects, as well as of parents and children, could not be more alien to our modern experience. If we refuse to take such values seriously, not only do we render the plots incomprehensible; we also cut ourselves off from a greater understanding of what human life has been and, by contrast, is now. Update Don Giovanni to a contemporary setting where a mandate of premarital chastity is unthinkable, for example, and make the peasant girl Zerlina and the noblewomen Donna Anna and Donna Elvira all aggressively promiscuous – as is the case in virtually every modernized version since Peter Sellars’s Spanish Harlem travesty – and Zerlina’s cries of desperation when Don Giovanni hustles her off for a conquest become absurd, as does the nobles’ response of “Soccorriamo l’innocente” (“Let us rescue the innocent girl!”). And the avenging triumvirate’s subsequent warnings to Don Giovanni that retribution awaits him are meaningless in the amoral universe in which Regietheater directors inevitably set the opera.

Regietheater promoters imply that following a composer’s intentions in staging a work is easy; genius lies in modernizing it. Mortier has even coyly suggested that his updating project gives him an affinity with Mozart. “You couldn’t name one great composer – not that I want to compare myself to them – who did not have to fight,” he says. “Think of Mozart selling his silverware to go to Frankfurt when the emperor could have given him a commission for his coronation.” In fact, finding a visual language to convey the meaning of the music and the world it represents is where directing makes its claim to greatness. Stephen Wadsworth, for example, is one of the most historically sensitive directors working today; his understated productions of Handel’s Rodelinda and Xerxes and of Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito at the Metropolitan Opera and New York City Opera are among those houses’ treasures. The slightest gesture of a hand in a Wadsworth staging can convey the refinement and melancholy of the Baroque. Such details are part of what he calls the “vernacular” of the past.

Wadsworth unapologetically embraces one of the most toxic words in the operatic lexicon today: “curating.” The last thing a solipsistic director wants to be accused of is lovingly preserving and transmitting the works of the past. Wadsworth, however, accepts the charge. Those given responsibility for an opera production are akin to those given responsibility for great paintings, he believes. “It is not our job to repaint them. We should only be concerned with: Where to hang it? How to light it? In what context? How do we present it to the public in a way that the public can appreciate what it is, perhaps even contextualize it in terms of that painter’s body of work or some other trend or school or idea? The list of curatorial concerns and responsibilities is long. And I think that a lot of productions that we see simply fail to meet them.”

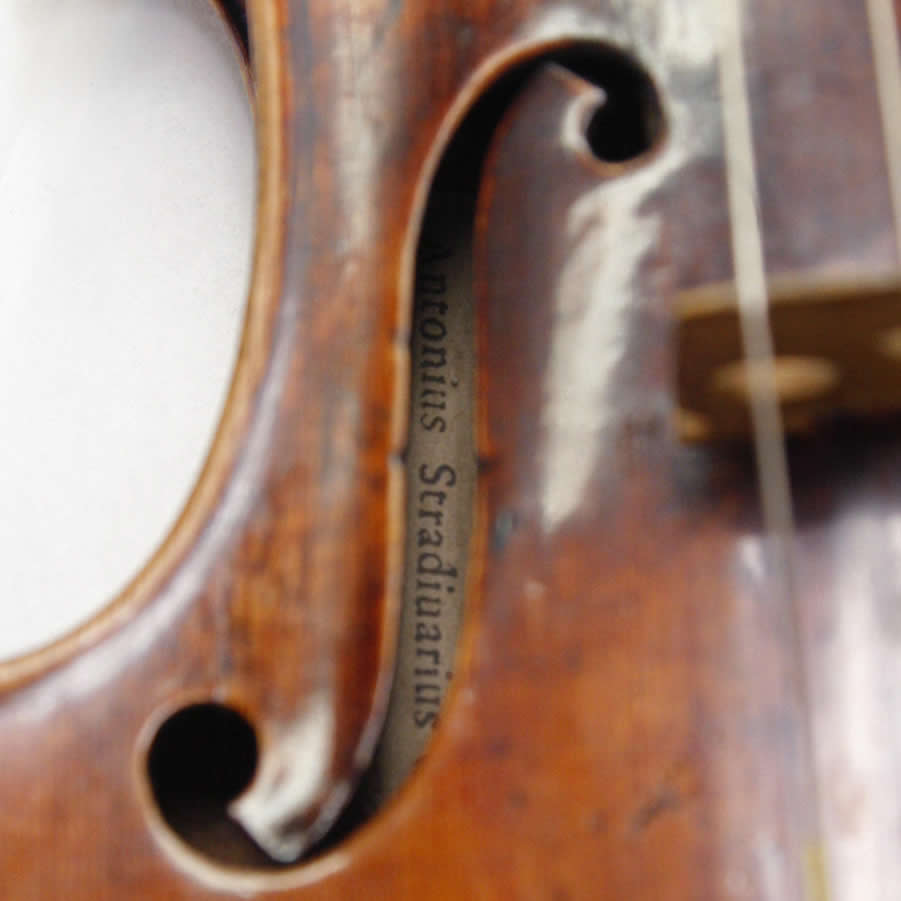

In a few decades, Regietheater opera has destroyed what took centuries to develop. Long before Wagner called for the Gesamtkunstwerk (the total work of art), opera composers sought to enforce in the productions of their works a unity of music and dramatic action. Arrayed against this synthesis were singers, who treated opera as simply a platform for virtuoso recitals, and stage designers, who tried to cram as many awe-inspiring but irrelevant special effects onto the stage as their arsenal of fireworks and machinery would allow.

By the twentieth century, however, a revolution in attitudes toward the music of the past was under way – fueled, no doubt, by the recognition that no more pieces like those wonders were coming along. Gone was the carefree mutilation of scores by publishers, conductors, and performers that had been standard throughout Western musical history. In its place, an unprecedented reverence for the composer’s work rose up. Singers reined in self-indulgences, and directors worked to unleash the music’s dramatic potential. A profile of the German director Carl Ebert in a 1950 issue of Opera magazine underscored the new standard: “For Ebert, the music dictates how the actor should move, should look, how the scenery should be planned in shape as well as in color. Ebert achieves with his singers something like visible music for the listener.”

Regietheater has reversed that revolution, producing a disjuncture between the music and the visual and dramatic aspects of a production that is unprecedented in operatic history. Even as every other aspect of the music business continues on the path of greater professionalization and devotion to authenticity, opera directors have received the license to ignore the basic mandates of a score and libretto. This bifurcation results in such weird pairings as a period-instrument ensemble in the orchestra pit, sawing away at Baroque instruments in the hope of sounding just like Prince Esterhazy’s court orchestra, while onstage, singers in baggy sweat pants, torn T-shirts, and baseball caps slouch through twenty-first-century cultural blight.

Standing against such disintegration is the Metropolitan Opera, regarded by the transcontinental opera establishment either with condescension or admiration as the last bastion of faithful production. The Met has always presented great singers and, more sporadically, renowned maestri, but for much of its existence the caliber of its stagings lagged behind that of its musical talent. This deficiency was due in large part to the woefully ill-designed backstage area of the opulent old opera house on West 39th Street, which housed the Met from its birth in 1883 until its move to Lincoln Center in 1966. When a taxi driver told Sir Thomas Beecham during World War II that he couldn’t take him to the Met because gas restrictions banned rides to places of entertainment, the conductor replied: “The Metropolitan Opera is not a place of entertainment, but a place of penance.” Stage discipline was often weak; some of the Met’s most famous singers simply refused to rehearse.

But despite the limitations of the old house, the Met’s greatest leaders progressively made the “sights… more harmonious with the sounds,” as Rudolf Bing, the aristocratic general manager from 1950 to 1972, promised upon taking over. Indeed, Peter Gelb often sounds as though he is channeling Sir Rudolf, who brought the best stage and film directors of his time to work at the Met. Bing’s theatrical ambitions were aided by a growing circle of donors, who paid for new productions, sometimes single-handedly, when the board was unwilling to front the money. Charismatic philanthropists like Mrs. August Belmont created novel mechanisms for harvesting private support, including the first women’s opera auxiliary guild. Even during the troubled 1960s and 1970s, when the Met struggled with union protests and severe budget problems, it forged ahead artistically, aided by the superb technical capacities of the new Lincoln Center facility.

The Met’s role as the guardian of opera integrity emerged in the 1980s and 1990s. As the abuse of composers’ intentions became more flagrant in Germany and then the rest of Europe, general manager Joseph Volpe deliberately separated the Met from the trend. “There was a conscious effort to avoid” Regietheater, says Joe Clark, the Met’s peerless technical manager. “The idea was to get the best possible director with the best musical sense. We weren’t always looking for traditional and realistic settings, but rather a realization that was musical and would show something appropriate to the opera.” Robert Wilson’s minimalist Lohengrin met that criterion as much as Zeffirelli’s opulent Turandot. Conductor James Levine, the most important music director in the Met’s history, is equally committed to fidelity to the music. “It is inspiring to work with a man who wants to put [an opera] on stage as the composer meant it,” Levine said recently, praising director Jack O’Brien’s staging of Puccini’s Il Trittico.

Regietheater advocates caricature the Met as addicted to lavish, overblown scenery, associated – again, in caricature – with such masters of realism as Franco Zeffirelli and Otto Schenk. In fact, no competing house can boast such a variety of production styles, says critic Charles Michener. But what really makes the Met stand out today is language like the following, from theater director Bart Sher, who mounted an energetic Barber of Seville this season. The Met is unique “among our many great institutions of public art and life,” Sher says, in its “capacity for creating beauty beyond the heart to hold. You sit there and go: ‘Western culture’s an incredible thing.’ ” It is unimaginable that the directors who create the most buzz in Europe today would use such language. Asked about a director’s responsibility to the beauty of a piece, Jonathan Miller responds: “To hell with beauty, it’s a kitsch notion; I don’t feel this business of being overwhelmed by it.” And Miller, unlike the most violative directors working today, actually has created productions of great delicacy, such as his 1990 Marriage of Figaro at Vienna’s Theater an der Wien.

Equally unthinkable from a Regietheater wunderkind is the unabashed enthusiasm of Broadway director O’Brien for the composer’s intentions. “The author and composer are my household gods,” says O’Brien, whose comic ensemble work in Il Trittico was infused with energy so taut as to make breathing difficult. “I don’t think that my opinion is more important than theirs; I don’t want to take my Magic Marker and scrawl over their works. Puccini’s knowledge, control, and insight into dramatic literature is staggering; there’s not a bar of music that is not dramatizable if you are sensitive to what the composer is asking you to do. I am never interested in a ‘point of view,’ only in making love to these pieces.”

Peter Gelb could do worse than make these sentiments a litmus test for every director he brings into the house: Can the prospect unashamedly use the words “beauty” and “love” to describe music? It is a positive sign that Bart Sher is one of Gelb’s additions to the Met’s directing roster (O’Brien, also new to the house this year, was hired by Volpe).

Gelb has said that the Met has become “artistically somewhat isolated from the rest of the world” and reliant on “somewhat conservative patterns of thinking,” and he has pledged to keep it “more broadly connected to contemporary society” through “exciting theatrical visions.” One hopes that he is speaking as the master promoter that he is, creating a sense of newness to attract new audiences – and not in anticipation of a move toward the less conservative “patterns of thinking” and “theatrical visions” prevalent in Europe.

Still, a dedicated opera fan can be forgiven for being a little worried about what exactly Gelb means, since Regietheater is nipping everywhere at the Met’s heels. Joseph Volpe says that as general manager, he constantly had to fend off demands for more “progressive” productions. “I was always criticized for not bringing in Peter Sellars,” he says, “but I was brought up with Zeffirelli and other great directors, for whom the intentions of the composer were of the utmost importance.” Sellars is in fact closing in, having turned Mozart’s Zaïde into a pretentious critique of sweatshops for Lincoln Center’s Mostly Mozart Festival last year, and having staged his video extravaganza, The Tristan Project, in Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall this year. And with Mortier bringing his relentless updating agenda to the New York City Opera in 2009, Gelb will face the most glamorous exponent of Regietheater right next door.

Ideally, Gelb will choose a strategy of product differentiation, branding the Met as the place where you can still see opera as its composers intended it. But if the press falls for Mortier – and some of New York’s critics already disparage any production that they find too traditional – Gelb may face pressure to go Euro.

If Gelb’s offerings to date exemplify his ideal of cutting-edge theatrics, the house will be well served. Anthony Minghella’s Madam Butterfly was a lacquered blaze of jewel-colored light; its stylized, Asian-influenced use of puppetry and props was beautiful and consistent with Puccini’s vision. Bart Sher’s Barber of Seville was even more reassuring. Despite Gelb’s efforts to package the production as a startling new twist on the story, primarily through an alleged emphasis on Figaro’s virility, neither that aspect of Figaro’s character nor the production itself represented a break from valid performance traditions. Sher simply directed an elegant, fast-paced Barber that pulsed with Rossini’s comic genius (despite two lapses from good taste: the gratuitous lesbian lovemaking in Figaro’s mobile barbershop and a wholly unmotivated visual pun on the name of a rock band that concluded the first act). The final production with a Gelb-chosen director this season – Richard Strauss’s Die Ägyptische Helena, mounted by David Fielding – took the greatest liberties with the setting, but Fielding’s storybook, surrealistic design matched the weirdly magical Hofmannsthal libretto without interpolating any self-indulgent political gloss.

The future, however, is more clouded, since some of Gelb’s hires for upcoming seasons have revisionist productions on their resumés. Luc Bondy, engaged for The Tales of Hoffmann in 2009, staged a bloody Idomeneo at La Scala this year that simply shaved off Mozart’s score when it conflicted with Bondy’s dark rewriting of the story; his Don Giovanni at the Vienna State Opera in 1990 was a bizarre farrago of historical and futuristic settings and costumes. Patrice Chéreau, scheduled to mount Janáček’s From the House of the Dead at the Met in 2009, directed a Ring cycle at Bayreuth in 1976 that became a landmark in Regietheater – and led to the formation of the Wagner Protection Society, so scandalized were patrons by Chéreau’s injection of anticapitalist, environmental politics into the story. His Janáček, however, reportedly avoids heavy revisionism. Matthew Bourne will be staging Carmen at the Met; he has already shown a predilection for homoerotic themes in that opera, as well as in two ballet productions, The Nutcracker and an all-male Swan Lake. Richard Jones is one of Britain’s bad boys of opera – but since his Hansel and Gretel at the Met next year is part of Gelb’s new holiday family programming, he will probably tone down his usual intrusions.

Having done transgressive work in the past need not disqualify directors from working at the Met, as long as Gelb makes clear at the outset that he is not interested in their opinions on contemporary class or sexual relations. Directors should be able to work with that stipulation. When Giancarlo del Monaco, who set Verdi’s Old Testament story Nabucco in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq for a German production, arrived at the Met in the early 1990s, he said: “I have a Eurotrash face for Europe and a classy face for the Americans.”

Gelb has made one unequivocal aesthetic stumble, however. In a bid to link the Met with the trendy downtown art scene, he commissioned an opera-inspired work from Richard Prince, among other art frauds, to display in a small new “art gallery” in the Met’s lobby. Prince’s contribution, “Madame Butterfly Is a Lesbian,” is a wall-size array of hundreds of cheap wallet-size porn shots of naked women engaged in lesbian sex. Scrawled over the photos is Prince’s idea of clever commentary: “I went to the opera. It was Madame Butterfly. I fell asleep. When I woke up the music was by Klaus Nomi and Cio-Cio-San had turned into a lesbian and refused to commit suicide. It was a German ending.” Apparently, neither Gelb nor anyone else in the Met’s press or fund-raising office was willing to say that such a work was inappropriate for a family institution seeking to spread the culture of opera, much less that it stank as art. Met patrons had better hope that the Prince display is just an aberration, of no deep meaning for the future.

The Met’s board and audience may restrain any inclination that Gelb might have to dabble in Regietheater, but the final check should be Gelb’s sense of the Met’s history. Generations of hard work and artistic passion have gone into the house’s current level of professional excellence. Gelb has sound business reasons for trumpeting a new beginning and an infusion of cutting-edge theatrical values. But it is important to remember how extraordinary the current state of the institution is. Though a certain type of opera lover perpetually mourns a lost golden age, arguably the golden age is now.

Gelb will earn a place in opera history if he maintains the Met’s artistic character while continuing the inspired promotional blitz that he has already begun. Nothing he touches in the area of marketing escapes a massive infusion of glamour; the brochure for the 2007–08 season is as luxurious as a Bergdorf Goodman Christmas catalog. “He’s a genius at selling,” says Herman Krawitz, who ran the Met’s complex backstage operations for years. “Gelb was a better press agent at age 18,” when he worked as an usher at the Met, “than anyone there.” His ideas for expanding the venues for opera – into movie theaters, schools, public spaces – are groundbreaking. “When he broadcast Madam Butterfly in Times Square, people here were amazed at the concept of this,” says Vienna-based critic Larry Lash. Gelb’s efforts are having a spillover effect: not only are other houses imitating his ideas – the Vienna State Opera will beam every performance into the plaza outside its house next season – but interest in local opera companies is rising in cities whose movie theaters have shown the Met’s productions.

As its season wound down this year, the Met had sold out every remaining seat – this, without having made a single step in the direction of trendy transgressive productions. Contrary to the usual hand-wringing about an aging audience, young and middle-aged adults already appear to make up a surprisingly high percentage of patrons. They are coming to see not a twisted rewriting

of the great works, but the thing itself, drawn to what opera promises: sublime musical beauty and human drama. For all the deservedly hyped new productions this year, the greatest experience to be had at the Met came in a production of Verdi’s Don Carlo first mounted in 1979. German bass René Pape turned the extraordinary opening scenes of Act 4, in which the authoritarian King Philip II of Spain confronts first his own emotional isolation and then the ruthless Grand Inquisitor, into an unbearable portrait of anguish. There were no cutting-edge theatrical techniques in those two scenes, just singing and acting that left one’s hair standing on end and one’s head pulsing with Verdi’s obsessive contrapuntal harmonies and dark grinding dissonances.

By all means, Gelb should commission as many new productions as his budget will allow, and then sell the pants off them, with all the creativity that he has already demonstrated. And certainly contemporary political commentary has a place at the Met – so long as it is integral to a new work, rather than strapped like a suicide bomb onto the back of an old one. But Gelb should remember that he is the guardian of a tradition that generations have built. That tradition approaches the magnificent works of the past with love and humility, recognizing our debt to them. The Met will remain a vital New York and world institution for another century if it allows those works to speak for themselves.