EDITOR’S NOTE: This essay is reprinted with gracious permission from Standpoint Magazine, where it was originally published in October 2011.

As a composer I have been affected by political considerations and developments over time, and in a range of different ways. Also, I seem to be a part of a huge international community of composers, past and present, that has been drawn towards folk music as a way of developing new, individual musical languages and palettes.

There has been a long history of the politics of traditional music affecting the aspirations and inspirations of composers. In the 19th century, the growing nationalism in central and eastern parts of Europe is plainly discernible in the work of many composers. Whole swathes of late 19th- and early 20th-century musical history are dominated by a roll call of their names — Glinka, Balakirev, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, Smetana, Dvorak, Janacek, Grieg, Sibelius, Granados, Vaughan Williams, and Skalkottas. Subsequently, nationalism has become tainted in artistic communities, not just because of the Third Reich but because more recent “big-gun” nationalisms, like Gaullism and Thatcherism, were of the Right.

This has caused a degree of anxious squirming in the world of traditional music, because that very traditionalism — the valuing and nurturing of ancient cultural practice — can so often be associated with nationalism, especially in the case of Ireland and Scotland. Indeed the attitudes of the Irish Left towards their traditional cultures of music, language, and dance during the 20th century were ambiguous and troubled, to say the least. The Irish Republic was built by rightists, nationalists, and Catholics on a range of traditional values as a bulwark to defend the Irish State and people from Bolshevism, liberalism, and the English Protestant crown. The sound of Irish traditional music was the very sound of defensive introspection in the face of a changing outside world — a changing outside world that the forces of the Irish Left sought to import and impose on their own nation.

Many and various ideological and aesthetical hoops have been jumped through over the decades for Irish traditional music to take its present place in the affections of the bien pensants. And in my own country there is still a deep insecurity over the question of Scottish nationalism: is it a creature of the Right or the Left? Even today, with the giddy ascent of Alex Salmond, there is no clear answer. The anxiety over the importance of our past exacerbates this question. Is the celebration of traditional Scottish values and culture a reactionary impetus? Or is it all part of a progressivist thrust towards self-determination in a spirit of local ownership of past identities?

In the discussion of folk music in Scotland, either in its grassroots place in cultural life, or in the work of its many composers, there is also clearly a degree of ambiguity. I have detected this in the music and conversations of my colleagues: honorary Scot Sir Peter Maxwell Davies, Alasdair Nicolson, James Dillon, Judith Weir, William Sweeney, Edward McGuire, and Lyell Cresswell — all have an abiding interest in folk music. This interest in folk cultures, when all is said and done, is purely musical. We are fascinated by what we have heard of Scotland’s ancient sounds and want to absorb it into our own souls again. This can be tricky when trying to explain ourselves to our foreign colleagues. The project of European high modernism in music has not looked kindly on “insular” rummaging forays into local folk music, especially on the Celtic fringe. The very localism of this instinct is an affront to the cosmopolitan sophistication which the international avant-garde was to develop over time. “But,” we squeal in self-defensive indignation, “what about Bartok, who was a musicologist in his own musical folk cultures as well as a major composer? Or the Italian avant-gardist Luciano Berio, for that matter?” Indeed, the fragmentation of international modernism has freed up so many potential avenues for composers in recent decades. And it is fascinating that a figure on the Left, like Berio, could have embraced folk music so wholeheartedly in his later years. Concurrently, there has been a steady fascination among English composers of the Left with music that is genuinely “of the people” — particularly the diversely opposing work of Michael Finnissy and Howard Skempton. Some of the composers mentioned in this paragraph featured together in a fascinating concert at the Bath Festival in May, involving pianist Joanna MacGregor, Northumbrian piper Kathryn Tickell, and the Navarra String Quartet.

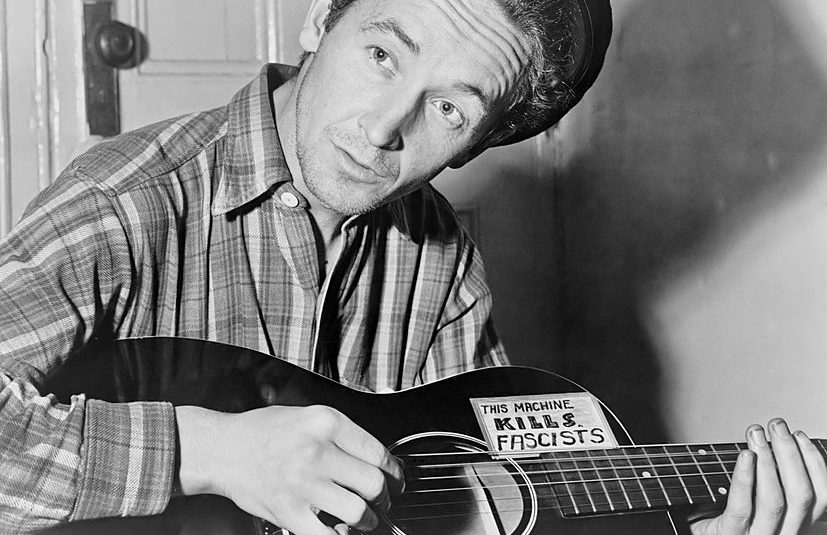

One of the central figures in this consideration of politics and folk music is Cornelius Cardew, whose music also appeared in the same programme. In 1968 Howard Skempton joined Cardew’s experimental music class at Morley College, where in spring 1969 they formed the Scratch Orchestra. This ensemble had open membership and was dedicated to performing experimental contemporary music.

However, apparently tensions arose during the politicising of the Scratch Orchestra in the early 1970s: Cardew and a number of other important members were pushing the ensemble in a Marxist direction. Skempton, and many others, refused to be associated with an extremist political line, and the break-up of the orchestra was accompanied by a split between its “political” and “experimental” factions.

The wider political fissures in this area of contemporary music are worth exploring here. The arcane and sometimes bloody ideological warfare on the Left between Trotskyists and Stalinists seems a thing of the past now. Not so in the world of contemporary classical music, apparently. An international conference was held at the British Academy in London last January, entitled “Red Strains: Music and Communism outside the Communist Bloc after 1945.”

With keynote speakers from Harvard, Cambridge, and many other universities here and abroad, the gathering explored the nature and extent of individual musicians’ involvement with Communist organisations and parties, the appeal and reach of different strands of Communist thought (e.g. Trotskyist, Castroist, Maoist), the significance of music for Communist parties and groups (e.g. groups’ cultural policies, use of music in rallies and meetings), the consequences of Communist involvement for composition and music-making, and how this involvement affected musicians’ careers and performance opportunities in different countries.

Topics ranged from “Communism’s cultural legacy: Soviet realism overseas” to “Marxist-Leninist ideology and British experimentalism.” The more eye-catching papers included “A Western Communist as a source for the second Soviet avant-garde: Luigi Nono’s first visit to the USSR in 1963 and its aftermath,” “Samuel Goldwyn, Aaron Copland, and the United States government: Developing a pro-Soviet aesthetic in Hollywood,” and “Left-wing and progressive musicians in the West and their relationship to Eastern bloc dissidents.” (It is well-known that many leftist artists, like left-wing Western intellectuals, had long and shameful love affairs with Soviet Communism.)

Cardew eventually rejected the ethos of the avant-garde by setting up the Scratch Orchestra, which promoted a kind of manufactured “music of the people”, concentrating on political liberation songs such as “Smash the social contract” and “There is only one lie, there is only one truth.” The inspiration for this was the Chinese cultural revolution. This political and aesthetical development was encapsulated in Cardew’s 1974 book Stockhausen Serves Imperialism, in which he renounced not only his earlier association with the musical avant-garde but his friendship with Stockhausen himself.

Cardew was active in various causes in British politics, such as the struggle against the revival of neo-Nazi groups and supporting striking miners and “anti-imperialist movements in Northern Ireland” (aka the Provisional IRA).

A member of various Maoist organisations in the 1970s, Cardew was killed in a hit-and-run car incident near his home in 1981. The driver was never found. Among the ultra-Left there are various conspiracy theories that he was killed by MI5, and he has subsequently developed martyrdom status in some old-guard, avant-garde musical circles.

However, as in all things ultra-Left, there has been a bitter Pythonesque schism among the comrades about Cardew’s true political legacy. A heretical paper was delivered at the British Academy conference which caused an almighty row. “Cardew serves Stalinism: Saint Cornelius and reified constructions of the international proletariat” by Ian Pace, (a formidable pianist and lecturer at City University, London), seems to have pushed a revisionist Trotskyist agenda. One delegate described it as a “diatribe against Mao, Stalin, Hoxha and, of course, Cardew.” (Imagine having the temerity to attack Hoxha. Tut tut. Whatever next?)

One delegate to the conference commented: “I was surprised at just how many people at the conference were actually Communists, rather than people studying music that bears some relationship to Communism. Lots of Americans, and mostly over 60. One guy had a guitar and illustrated his daughter’s paper with live musical examples, including ‘Where have all the flowers gone?’ and other 1960s favourites, and most of the audience joined in with all these songs.

“One woman — a professor from Harvard — even had tears in her eyes by the end of one of them. Not quite what I was expecting, and somewhat surreal, but educational more in a sociological than academic way. They all seemed like very friendly and good people, but the sentimentality of the idealism, and the borderline hippy-culture…”

I wish I had been there. I could have relived my youth. As a younger man, I was very interested in the way that Cardew thought to engage the community in music-making, even if this was politically-motivated. In that sense you could say that he has had a big impact on the development of musical education and outreach work undertaken by many ensembles and organisations in the decades since his death. I am specifically referring to those projects which aim to take music into communities which, traditionally, don’t have much contact with the world of “art” music — certain schools and prisons, for example.

You could say that pioneers of this work like Gillian Moore, Richard McNicol, and Peter Wiegold have been influenced by some of this early thinking. I was particularly struck by the story of Cardew joining the picket line at Grunwick and trying to teach the men some chants and songs he had specially written. This is real composer-in-the-community stuff and not too far removed from the work explored by Peter Maxwell Davies in Orkney and elsewhere. I also hear that the Grunwick heavies told him to f*** off, but that is neither here nor there. I have been approached by members of the Green and White Brigade (a group of noisy Celtic fans) to write new stuff for them at Celtic Park, but I hesitate as I don’t want to alienate them in the Cardew/Grunwick manner.

One of my most enjoyable projects as a student was being asked to return home and make notes of where live music was being used in my community. This was Ayrshire, and the town was full of coalminers and other manual workers; that is, the kind of people that the latte-sippers of the liberal-Left metropolitan elite wouldn’t recognise as the proletariat even if they trod on them.

Anyway, it was an illuminating experiment and led to an abiding interest in not just ethnomusicology, but the sociology of music generally. I was on the Left at that time, not the loony Trot wing of course — only the genuinely swivel-eyed get involved with them — rather, I had been in the Young Communist League and in and out of the Labour Party (until the early 1990s). I was a branch chairman during the miners’ strike and delegate to my constituency party, as part of a kind of Bennite caucus, I suppose. I encountered the ultra-Left groups at street level during that time and came quickly to the conclusion that they were jam-packed with poor little rich kids simply masquerading as the proletariat. Something of that aura can be palpable in artistic communities too, where a received and fashionable left-wing orthodoxy is de rigeur.

Nevertheless, Cardew has had an influence on me too. I love working in the kind of community outreach programmes I mentioned earlier, which have had the input of many composers now, over the last few decades. But the real challenge in these is to take the concept of music-making into working-class communities and try to get them involved. Where today can one hear working-class people making music, apart from at football games? Well, one answer is in Roman Catholic churches in places like Glasgow, Liverpool, and Birmingham. Ever since the Second Vatican Council the Church has been involved in generating wider, fuller involvement in the liturgy so that ordinary lay people would feel engaged in the divine praises of the church. That means creating new music for them to sing, sometimes on a weekly basis. In the Dominican church in Maryhill, Glasgow, every week I write a responsorial psalm which I teach to the congregation (Cardew/Grunwick style) just before Mass begins. They therefore sing new music on a regular basis, and this composer is fully involved in the life of his community. Do I have Cardew to thank for that? Very possibly.

So perhaps Ian Pace was right after all; perhaps we are correct to talk of “Saint Cornelius” right enough. Cantate Domino canticum novum, comrades.