My first real job playing trumpet was in a Mexican orchestra, high up in the mountains beyond Mexico City, under the snow-capped peaks in Toluca. What a blast! I thought I had died and gone to heaven.

I say it was my first real job because it offered me for the first time a great monthly salary, at least given the low cost of living down there. And it even paid everyone for a 13th month – you know, for Christmas expenses. I did not, however, get my own locker. (That would have to wait until my next job.) But then nobody did: we were expected to show up dressed in our tails – outfits that nobody remarked upon as being somehow backwards. Tails or tuxedos were simply what orchestras wore, as they do worldwide. By local standards, compared to the mariachis walking around town, we were positively trendy. The town of Toluca itself was unremarkable. I’m sure you would never see it in a travel brochure. It was notable only for having the largest flea market and best chorizo around. And an orchestra.

Our conductor was an HR department’s worst nightmare. Imagine a cross between the perversions of Harvey Weinstein and the tantrums of Buddy Rich, and then throw some matador in there for flavor. I will not attempt to give accounts of what transpired in rehearsals as the reader simply would not believe me. There was no HR department, however – just a few staffers who ran around putting out fires and setting up music stands for our fourth-generation photocopied parts.

I also taught at the conservatorio where I had a studio bursting at the seams with eager young trumpeters who still worshipped the patron saint of lightning fast staccato trumpet playing, Raphael Mendez, born just over the mountains in Michoacán. In the eco-system of that school, trumpet and guitar were at the top of the food chain, and “less useful†instruments like cello and piano had to eat our scraps. Almost all these young trompetistas came from one village, Metapec, where most worked as carpenters making furniture and the mandatory hobby was playing in the local banda, numbering 500 players. One can imagine what kind of fiestas go on in a village where everyone plays music!

Concerts were celebratory, tremendous outpourings of enthusiasm for classical music and the musicos who play it. The audience, as is customary, showered roses on the orchestra from time to time. As we were the orchestra that represented the State of Mexico, we covered that entire territory with frequent forays into the countryside.

On the Sunday afternoons when we ventured out, we would, without fail, get lost on the long bus ride out to uncharted villages to play in their local churches, which were always large and opulent no matter how far they were off the map. During the panic to find these places, as if scripted, the bus driver would always ask an old lady selling tortillas and cactus by the roadside for directions, which she gladly provided regardless of whether or not she had any real idea where we were going or how to get there. Other times, we would go to a large outdoor venue somewhere outside the big city and there play the same heavy program we played indoors the night before.

The audiences always showed up and always cheered mightily. One year, we made it our routine, upon returning home after our Sunday concerts, to turn on the tuba player’s bulging black-and-white TV, to fiddle with the coat-hanger antennae, pull out a case of Negro Modelo cervezas, and watch the Orquesta Nacional play their televised, complete Mahler cycle. Highly entertaining it was – a bit like going to the demolition derby. They, like the numerous other professional orchestras in Mexico City, had their own audience, loyal to only them – like White Sox fans who won’t go to Cubs games. And theirs was the first Mahler cycle in Mexico, having about it the air of what must have transpired during the weeks of rehearsals before the premiere of Rite of Spring in 1913.

The only exception to filled houses were those weeks when none of the three administrators who ran things remembered to tell anyone in the public, by way of what these days we call “marketing†but in those days was basically a sign on the hall or an ad in the newspaper, that we were holding a concert that week. In cases of such oversight, practically nobody showed up.

We played a variety of war-horses and obscure music, all of it good – a breadth that I would never span again in my career. Bruckner Masses and symphonies, Tchaikovsky’s orchestral suites, Beethoven rarities like Ruins of Athens, anything by Turina or Albeniz, and works by Debussy that I never heard again. Early forgotten symphonies of Stravinsky and Rimsky-Korsakov, Copland’s less than greatest hits. Anything by Strauss, either Richard or uncle Johann. Soloists would get edged out by muscular programming, such as an evening of Sibelius’s 2nd and Shostakovich’s 5th followed by Wagner’s Rienzi Overture as an encore. We even recorded all of Verdi’s and Rossini’s overtures, offering me an education in just how many of those gems there are. Our audiences ate it all up. And Mexico has its own classical music canon revolving around Revueltas and Chavez, the beauty of which should not be lost on artistic planners.

We reached the greatest number of people with our outdoor concerts – many thousands in one fell swoop. I remember vividly playing in a town zócalo and seeing the Indian women with babies wrapped about them quietly contemplating Beethoven’s 7th. During another concert in a distant village one Sunday after Mass, a mysterious, mustachioed man rode into the dusty church on his horse to figure out what was going on with Tchaikovsky’s 4th. The locals were drawn to classical music for what it most simply is: a spectacle of magnificence.

Given my experiences in Mexico, my lingering question has been, “Who decided, or why do we feel, that we must upend our programming in order for people of targeted ethnicities to comprehend and enjoy classical music played by a live orchestra?†It strikes me as suspiciously odd that, for all our talk about the universality of classical music, administrators, and, certainly some musicians, when they think of specific ethnic groups, must suddenly condescend to them, patronizingly and awkwardly changing what we do to suit all the clichés.

There are Mexicans in Mexico and Mexicans in the US, but only individual Mexicans attend classical concerts either here or there. It may be a conceit of planners that we can put out special bait for an entire group or that any one community leader speaks for them, as if there was a hive mind we can tap into. Only individuals choose to attend classical music concerts – and for personal reasons. Entire groups do not.

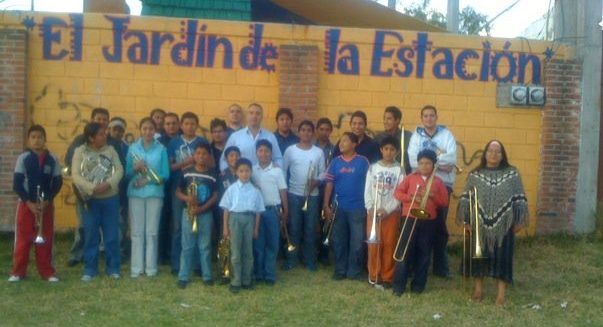

I was certain, by the time I moved away from Mexico, that Mexicans enjoyed and appreciated classical music as much as anyone else in this world. Of course, many Mexicans never went to orchestra concerts. But to be certain, those who did also loved to dance in their neighborhood street parties, called pachangas, and at weddings that started solemnly in churches with Mozart’s Coronation Mass and Schubert’s Ave Maria and ended with mariachis raising the dead at the late night cena. What with the huge families they had, that meant a wedding just about every month. Today, not only do most Mexican cities have their own orchestras but every single state has a robust youth orchestra, too, as part of their far-reaching Esperanza Azteca Foundation program.

And they do this, not because they don’t have other societal problems, including true material poverty or a vast and bloody drug war spreading every which way, but because music, the best music, is self-evidently and intrinsically good by their estimation, a testament to and reminder of human flourishing and accomplishment. It is a cornerstone of a good life.

I think of those days, a lifetime and a world away, whenever I hear the intelligentsia up here talk about what our various “under-served communities†need in order to cross an imaginary chasm in order to be able “to understand†our music, which we are told must be so alien to them.