[In] sound itself, there is a readiness to be ordered by the spirit and this is seen at its most sublime in music.

—Max Picard

Despite the popular Romantic conception of creative artists as inspired madmen, composers are not idiots savants, distilling their musical inspiration from the ether. Rather, in their creative work they respond and give voice to certain metaphysical visions. Most composers speak explicitly in philosophical terms about the nature of the reality that they try to reflect. When the forms of musical expression change radically, it is always because the underlying metaphysical grasp of reality has changed as well. Music is, in a way, the sound of metaphysics, or metaphysics in sound.

Music in the Western world was shaped by a shared conception of reality so profound that it endured for some twenty-five hundred years. As a result, the means of music remained essentially the same – at least to the extent that what was called music could always have been recognized as such by its forbearers, as much as they might have disapproved of its specific style. But by the early twentieth century, this was no longer true. Music was re-conceptualized so completely that it could no longer be experienced as music, i.e. with melody, harmony, and rhythm. This catastrophic rupture, expressed especially in the works of Arnold Schoenberg and John Cage, is often celebrated as just another change in the techniques of music, a further point along the parade of progress in the arts. It was, however, a reflection of a deeper metaphysical divide that severed the composer from any meaningful contact with external reality. As a result, musical art was reduced to the arbitrary manipulation of fragments of sound.

Here, I will sketch of the philosophical presuppositions that undergirded the Western conception of music for most of its existence and then examine the character of the change music underwent in the twentieth century. I will conclude with a reflection on the recovery of music in our own time and the reasons for it, as exemplified in the works of two contemporary composers, the Dane Vagn Holmboe and the American John Adams.

According to tradition, the harmonic structure of music was discovered by Pythagoras about the fifth century BC. Pythagoras experimented with a stretched piece of cord. When plucked, the cord sounded a certain note. When halved in length and plucked again, the cord sounded a higher note completely consonant with the first. In fact, it was the same note at a higher pitch. Pythagoras had discovered the ratio, 2:1, of the octave. Further experiments, plucking the string two-thirds of its original length produced a perfect fifth in the ratio of 3:2. When a three-quarters length of cord was plucked, a perfect fourth was sounded in the ratio of 4:3, and so forth. These sounds were all consonant and extremely pleasing to the ear. The significance that Pythagoras attributed to this discovery cannot be overestimated. Pythagoras thought that number was the key to the universe. When he found that harmonic music is expressed in exact numerical ratios of whole numbers, he concluded that music was the ordering principle of the world. The fact that music was denominated in exact numerical ratios demonstrated to him the intelligibility of reality and the existence of a reasoning intelligence behind it.

Pythagoras wondered about the relationship of these ratios to the larger world. (The Greek word for ratio is logos, which also means reason or word.) He considered that the harmonious sounds that men make, either with their instruments or in their singing, were an approximation of a larger harmony that existed in the universe, also expressed by numbers, which was “the music of the spheres.” As Aristotle explained in the Metaphysics, the Pythagoreans “supposed the elements of numbers to be the elements of all things, and the whole heaven to be a musical scale and a number.” This was meant literally. The heavenly spheres and their rotations through the sky produced tones at various levels, and in concert, these tones made a harmonious sound that man’s music, at its best, could approximate. Music was number made audible. Music was man’s participation in the harmony of the universe.

This discovery was fraught with ethical significance. By participating in heavenly harmony, music could induce spiritual harmony in the soul. Following Pythagoras, Plato taught that “rhythm and harmony find their way into the inward places of the soul, on which they mightily fasten, imparting grace, and making the soul of him who is rightly educated graceful.” In the Republic, Plato showed the political import of music’s power by invoking Damon of Athens as his musical authority. Damon said that he would rather control the modes of music in a city than its laws, because the modes of music have a more decisive effect on the formation of the character of citizens. The ancient Greeks were also wary of music’s power because they understood that, just as there was harmony, there was disharmony. Musical discord could distort the spirit, just as musical concord could properly dispose it.

This idea of “the music of the spheres” runs through the history of Western civilization with an extraordinary consistency, even up to the twentieth century. At first it was meant literally, later poetically. Either way, music was seen more as a discovery than a creation, because it relied on pre-existing principles of order in nature for its operation. It is instructive to look briefly at the reiteration of this teaching in the writings of several major thinkers to appreciate its enduring significance as well as the radical nature of the challenge to it in the twentieth century.

In the first century BC, Cicero spelled out Plato’s teaching in the last chapter of his De Republica. In “Scipio’s Dream,” Cicero has Scipio Africanus asking the question, “What is that great and pleasing sound?” The answer comes, “That is the concord of tones separated by unequal but nevertheless carefully proportional intervals, caused by the rapid motion of the spheres themselves…. Skilled men imitating this harmony on stringed instruments and in singing have gained for themselves a return to this region, as have those who have cultivated their exceptional abilities to search for divine truths.” Cicero claims that music can return man to a paradise lost. It is a form of communion with divine truth.

In the late second century AD, St. Clement of Alexandria baptized the classical Greek and Roman understanding of music in his Exhortation to the Greeks. The transcendent God of Christianity gave new and somewhat different meanings to the “music of the spheres.” Using Old Testament imagery from the Psalms, St. Clement said that there is a “New Song,” far superior to the Orphic myths of the pagans. The “New Song” is Christ, the Logos Himself: “it is this [New Song] that composed the entire creation into melodious order, and tuned into concert the discord of the elements, that the whole universe may be in harmony with it.” It is Christ who “arranged in harmonious order this great world, yes, and the little world of man, body and soul together; and on this many-voiced instrument he makes music to God and sings to [the accompaniment of] the human instrument.” By appropriating the classical view, St. Clement was able to show that music participated in the divine by praising God and partaking in the harmonious order of which He was the composer. But music’s end or goal was now higher, because Christ is higher than the created cosmos. Cicero had spoken of the divine region to which music is supposed to transport man. That region was literally within the heavens. With Christianity, the divine region becomes both transcendent and personal because Logos is Christ. The new purpose of music is to make the transcendent perceptible in the “New Song.”

The early sixth century AD had two especially distinguished Roman proponents of the classical view of music, both of whom served at various times in high offices to the Ostrogoth king, Theodoric. Cassiodorus was secretary to Theodoric. He wrote a massive work called Institutiones, which echoes Plato’s teaching on the ethical content of music, as well as Pythagoras’s on the power of number. Cassiodorus taught that “music indeed is the knowledge of apt modulation. If we live virtuously, we are constantly proved to be under its discipline, but when we sin, we are without music. The heavens and the earth and indeed all things in them which are directed by a higher power share in the discipline of music, for Pythagoras attests that this universe was founded by and can be governed by music.”

Boethius served as consul to Theodoric in AD 510. Among his writings was The Principles of Music, a book that had enormous influence through the Middle Ages and beyond. Boethius said that

music is related not only to speculation, but to morality as well, for nothing is more consistent with human nature than to be soothed by sweet modes and disturbed by their opposites. Thus we can begin to understand the apt doctrine of Plato, which holds that the whole of the universe is united by a musical concord. For when we compare that which is coherently and harmoniously joined together within our own being with that which is coherently and harmoniously joined together in sound – that is, that which gives us pleasure – so we come to recognize that we ourselves are united according to the same principle of similarity.

It is not necessary to cite further examples after Boethius because The Principles of Music was so influential that it held sway for centuries thereafter. It was the standard music theory text at Oxford until 1856.

The hieratic role of music even survived into the twentieth century with composers like Jean Sibelius. Sibelius harkened back to St. Clement when he wrote that “the essence of man’s being is his striving after God. It [the composition of music] is brought to life by means of the logos, the divine in art. That is the only thing that has significance.” But this vision was lost for most of the twentieth century because the belief on which it was based was lost.

Philosophical propositions have a very direct and profound impact upon composers and what they do. John Adams, one of the most popular American composers today, said that he had “learned in college that tonality died somewhere around the time that Nietzsche’s God died, and I believed it.” The connection is quite compelling. At the same time God disappears, so does the intelligible order in creation. If there is no God, Nature no longer serves as a reflection of its Creator. If you lose the Logos of St. Clement, you also lose the ratio (logos) of Pythagoras. Nature is stripped of its normative power. This is just as much a problem for music as it is for philosophy.

The systematic fragmentation of music was the logical working out of the premise that music is not governed by mathematical relationships and laws that inhere in the structure of a hierarchical and ordered universe, but is wholly constructed by man and therefore essentially without limits or definition. Tonality, as the pre-existing principle of order in the world of sound, goes the same way as the objective moral order. So how does one organize the mess that is left once God departs? If there is no pre-existing intelligible order to go out to and apprehend, and to search through for what lies beyond it – which is the Creator – what then is music supposed to express? If external order does not exist, then music turns inward. It collapses in on itself and becomes an obsession with technique. Any ordering of things, musical or otherwise, becomes simply the whim of man’s will.

Without a “music of the spheres” to approximate, modern music, like the other arts, began to unravel. Music’s self-destruction became logically imperative once it undermined its own foundation. In the 1920s, Arnold Schoenberg unleashed the centrifugal forces of disintegration in music through his denial of tonality. Schoenberg contended that tonality does not exist in nature as the very property of sound itself, as Pythagoras had claimed, but was simply an arbitrary construct of man, a convention. This assertion was not the result of a new scientific discovery about the acoustical nature of sound, but of a desire to demote the metaphysical status of nature. Schoenberg was irritated that “tonality does not serve, [but] must be served.” Rather than conform himself to reality, he preferred to command reality to conform itself to him. As he said, “I can provide rules for almost anything.” Like Pythagoras, Schoenberg believed that number was the key to the universe. Unlike Pythagoras, he believed his manipulation of number could alter that reality in a profound way. Schoenberg’s gnostic impulse is confirmed by his extraordinary obsession with numerology, which would not allow him to finish a composition until its opus number corresponded with the correct number of the calendar date.

Schoenberg proposed to erase the distinction between tonality and atonality by immersing man in atonal music until, through habituation, it became the new convention. Then discords would be heard as concords. As he wrote, “The emancipation of dissonance is at present accomplished and twelve-tone music in the near future will no longer be rejected because of ‘discords.’” Anyone who claims that, through his system, the listener shall hear dissonance as consonance is engaged in reconstituting reality.

Of his achievement, Schoenberg said, “I am conscious of having removed all traces of a past aesthetic.” In fact, he declared himself “cured of the delusion that the artist’s aim is to create beauty.” This statement is terrifying in its implications when one considers what is at stake in beauty. Simone Weil wrote that “we love the beauty of the world because we sense behind it the presence of something akin to that wisdom we should like to possess to slake our thirst for good.” All beauty is reflected beauty. Smudge out the reflection and not only is the mirror useless but the path to the source of beauty is barred. Ugliness, the aesthetic analogue to evil, becomes the new norm. Schoenberg’s remark represents a total rupture with the Western musical tradition.

The loss of tonality was also devastating at the practical level of composition because tonality is the key structure of music. Schoenberg took the twelve equal semi-tones from the chromatic scale and declared that music must be written in such a way that each of these twelve semi-tones has to be used before repeating any one of them. If one of these semi-tones was repeated before all eleven others were sounded, it might create an anchor for the ear which could recognize what is going on in the music harmonically. The twelve-tone system guarantees the listener’s disorientation.

Tonality is what allows music to express movement – away from or towards a state of tension or relaxation, a sense of motion through a series of crises and conflicts which can then come to resolution. Without it, music loses harmony and melody. Its structural force collapses. Gutting music of tonality is like removing grapes from wine. You can go through all the motions of making wine without grapes but there will be no wine at the end of the process. Similarly, if you deliberately and systematically remove all audible overtone relationships from music, you can go though the process of composition, but the end product will not be comprehensible as music. This is not a change in technique; it is the replacement of art by ideology.

Schoenberg’s disciples applauded the emancipation of dissonance but soon preferred to follow the centrifugal forces that Schoenberg had unleashed beyond their master’s rules. Pierre Boulez thought that it was not enough to systematize dissonance in twelve-tone rows. If you have a system, why not systematize everything? He applied the same principle of the tone-row to pitch, duration, tone production, intensity and timber, every element of music. In 1952, Boulez announced that “every musician who has not felt – we do not say understood but felt – the necessity of the serial language is USELESS.” Boulez also proclaimed, “Once the past has been got out of the way, one need think only of oneself.” Here is the narcissistic antithesis of the classical view of music, the whole point of which was to draw a person up into something larger than himself.

The dissection of the language of music continued as, successively, each isolated element was elevated into its own autonomous whole. Schoenberg’s disciples agreed that tonality is simply a convention, but saw that, so too, is twelve-tone music. If you are going to emancipate dissonance, why organize it? Why even have twelve-tone themes? Why bother with pitch at all? Edgar Varese rejected the twelve-tone system as arbitrary and restrictive. He searched for the “bomb that would explode the musical world and allow all sounds to come rushing into it through the resulting breach.” When he exploded it in his piece Hyperprism, Olin Downes, a famous New York music critic, called it “a catastrophe in a boiler factory.” Still, Varese did not carry the inner logic of the “emancipation of dissonance” through to its logical conclusion. His noise was still formulated; it was organized. There were indications in the score as to exactly when the boiler should explode.

What was needed, according to John Cage (1912–1992), was to have absolutely no organization. Typical of Cage were compositions whose notes were based on the irregularities in the composition paper he used, notes selected by tossing dice, or from the use of charts derived from the Chinese I Ching. Those were his more conventional works. Other “compositions” included the simultaneous twirling of the knobs of twelve radios, the sounds from records playing on unsynchronized variable speed turntables, or the sounds produced by tape recordings of music that had been sliced up and randomly reassembled. Not surprisingly, Cage was one of the progenitors of the “happenings” that were fashionable in the 1970s. He presented concerts of kitchen sounds and the sounds of the human body amplified through loudspeakers. Perhaps Cage’s most notorious work was his 4’33” during which the performer silently sits with his instrument for that exact period of time, then rises and leaves the stage. The “music” is whatever extraneous noises the audience hears in the silence the performer has created. In his book Silence, Cage announced, “Here we are. Let us say Yes to our presence together in Chaos.”

What was the purpose of all this? Precisely to make the point that there is no purpose, or to express what Cage called a “purposeful purposelessness,” the aim of which was to emancipate people from the tyranny of meaning. The extent of his success can be judged by the verdict rendered in the prestigious New Grove Dictionary of Music, which says Cage “has had a greater impact on world music than any other American composer of the twentieth century.”

Cage’s view of reality has a very clear provenance. Cage himself acknowledged three principal gurus: Eric Satie (a French composer), Henry David Thoreau, and Buckminster Fuller – three relative lightweights who could not among them account for Cage’s radical thinking. The prevalent influence on Cage seems instead to have been Jean Jacques Rousseau, though he goes unmentioned in Cage’s many obiter dicta. Cage’s similarities with Rousseau are too uncanny to have been accidental.

With his noise, Cage worked out musically the full implications of Rousseau’s non-teleological view of nature in his Second Discourse. Cage did for music what Rousseau did for political philosophy. Perhaps the most profoundly anti-Aristotelian philosopher of the eighteenth century, Rousseau turned Aristotle’s notion of nature on its head. Aristotle said that nature defined not only what man is, but what he should be. Rousseau countered that nature is not an end – a telos – but a beginning: man’s end is his beginning. There is nothing he “ought” to become, no moral imperative. There is no purpose in man or nature; existence is therefore bereft of any rational principle. Rousseau asserted that man by nature was not a social or political animal endowed with reason. What man has become is the result, not of nature, but of accident. And the society resulting from that accident has corrupted man.

According to Rousseau, man was originally isolated in the state of nature, where the pure “sentiment of his own existence” was such that “one suffices to oneself, like God.” Yet this self-satisfied god was asocial and pre-rational. Only by accident did man come into association with others. Somehow, this accident ignited his reason. Through his association with others, man lost his self-sufficient “sentiment of his own existence.” He became alienated. He began to live in the esteem of others instead of in his own self-esteem.

Rousseau knew that the pre-rational, asocial state of nature was lost forever, but thought that an all-powerful state could ameliorate the situation of alienated man. The state could restore a simulacrum of that original well-being by removing all man’s subsidiary social relationships. By destroying man’s familial, social, and political ties, the state could make each individual totally dependent on the state, and independent of each other. The state is the vehicle for bringing people together so that they can be apart: a sort of radical individualism under state sponsorship.

It is necessary to pay this much attention to Rousseau because Cage shares his denigration of reason, the same notion of alienation, and a similar solution to it. In both men, the primacy of the accidental eliminates nature as a normative guide and becomes the foundation for man’s total freedom. Like Rousseau’s man in the state of nature, Cage said, “I strive toward the non-mental.” The quest is to “provide a music free from one’s memory and imagination.” If man is the product of accident, his music should likewise be accidental. Life itself is very fine “once one gets one’s mind and one’s desires out of the way and lets it act of its own accord.”

But what is its own accord? Of music, Cage said, “The requiring that many parts be played in a particular togetherness is not an accurate representation of how things are” in nature, because in nature there is no order. In other words, life’s accord is that there is no accord. As a result, Cage desired “a society where you can do anything at all.” He warned that one has “to be as careful as possible not to form any ideas about what each person should or should not do.” He was “committed to letting everything happen, to making everything that happens acceptable.”

At the Stony Point experimental arts community where he spent his summers, Cage observed that each summer’s sabbatical produced numerous divorces. So, he concluded, “all the couples who come to the community and stay there end up separating. In reality, our community is a community for separation.” Rousseau could not have stated his ideal better. Nor could Cage have made the same point in his art more clearly. For instance, in his long collaboration with choreographer Merce Cunningham, Cage wrote ballet scores completely unconnected to and independent of Cunningham’s choreography. The orchestra and dancers rehearsed separately and appeared together for the first time at the premiere performance. The dancers’ movements have nothing to do with the music. The audience is left to make of these random juxtapositions what it will. There is no shared experience – except of disconnectedness. The dancers, musicians, and audience have all come together in order to be apart.

According to Cage, the realization of the disconnectedness of things creates opportunities for wholeness. “I said that since the sounds were sounds this gave people hearing them the chance to be people, centered within themselves where they actually are, not off artificially in the distance as they are accustomed to be, trying to figure out what is being said by some artist by means of sounds.” Here, in his own way, Cage captures Rousseau’s notion of alienation. People are alienated from themselves because they are living in the esteem of others. Cage’s noise can help them let go of false notions of order, to “let sounds be themselves, rather than vehicles for man-made theories,” and to return within themselves to the sentiment of their own existence. Cage said, “Our intention is to affirm this life, not bring order out of chaos or to suggest improvements in creation, but simply to wake up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent….”

That sounds appealing, even humble, and helps to explain Cage’s appeal. In fact, Cage repeatedly insisted on the integrity of an external reality that exists without our permission. It is a good point to make and, as far as it goes, protects us from solipsists of every stripe. Man violates this integrity by projecting meanings upon reality that are not there. That, of course, is the distortion of reality at the heart of every modern ideology. For Cage, however, it is the inference of any meaning at all that is the distorting imposition. This is the real problem with letting “sounds be themselves,” and letting other things be as they are, because it begs the question, “What are they?” Because of Cage’s grounding in Rousseau, we cannot answer this question. What is the significance of reality’s integrity if it is not intelligible, if there is not a rational principle animating it? If creation does not speak to us in some way, if things are not intelligible, are we? Where does “leaving things as they are” leave us?

From the traditional Western perspective, it leaves us completely adrift. The Greco-Judeo-Christian conviction is that nature bespeaks an intelligibility that derives from a transcendent source. Speaking from the heart of that tradition, St. Paul in his Letter to the Romans said, “Ever since the creation of the world, the invisible existence of God and his everlasting power have been clearly seen by the mind’s understanding of created things.” By denigrating reason and denying creation’s intelligibility, Cage severed this link to the Creator. Cage’s espousal of accidental noise is the logically apt result. Noise is incapable of pointing beyond itself. Noise is the black hole of the sound world. It sucks everything into itself. If reality is unintelligible, then noise is its perfect reflection, because it too is unintelligible.

Having endured the worst, the twentieth century has also witnessed an extraordinary recovery from the damage inflicted by Schoenberg in his totalitarian systematization of sound and by Cage in his mindless immersion in noise. Some composers, like Vagn Holmboe (1909–1996) in Denmark, resisted from the start. Others, like John Adams (b. 1947) in America, rebelled and returned to tonal music. It is worth examining, even briefly, the terms of this recovery in the works of these two composers because their language reconnects us to the worlds of Pythagoras and Saint Clement. Their works are symptomatic of the broader recovery of reality in the music of our time.

In Vagn Holmboe’s music, most particularly in his thirteen symphonies, one can once again detect the “music of the spheres” in their rotation. Holmboe’s impulse was to move outward and upward. His music reveals the constellations in their swirling orbits, cosmic forces, a universe of tremendous complexity, but also of coherence. Holmboe’s music is rooted and real. It reflects nature, but not in a pastoral way; this is not a musical evocation of bird songs or sunsets. Neither is it an evocation of nature as the nineteenth century understood nature – principally as a landscape upon which to project one’s own emotions. To say his work is visionary would be an understatement.

Holmboe’s approach to composition was quite Aristotelian: the thematic material defines its own development. What a thing is (its essence) is fully revealed through its completion (its existence) – through the thorough exploration of the potential of its basic materials. The overall effect is cumulative and the impact powerful. Holmboe found his unique voice through a technique he called metamorphosis. Holmboe wrote, “Metamorphosis is based on a process of development that transforms one matter into another, without it losing its identity.” Most importantly, metamorphosis “has a goal; it brings order to the process and enables it to create a pattern of the same perfection and balance as, for example, a classical sonata.” Holmboe’s metamorphosis is something like the Beethovenian method of arguing short motives; a few hammered chords can generate the thematic material for the whole work.

Holmboe’s technique also has a larger significance. Danish composer Karl Aage Rasmussen observed that Holmboe’s metamorphosis has striking similarities with the constructive principles employed by Arnold Schoenberg in his twelve-tone music. However, says Rasmussen, “Schoenberg found his arguments in history while Holmboe’s come from nature.” This difference is decisive since the distinction is metaphysical. History is the authority for those, like Rousseau, who believe that man’s nature is the product of accident and therefore malleable. Nature is the authority for those who believe man’s essence is permanently ordered to a transcendent good. The argument from history leads to creation ex nihilo, not so much in imitation of God as a replacement for Him – as was evident in the ideologies of Marxism and Nazism that plagued the twentieth century. The argument from nature leads to creation in cooperation with the Creator.

Rasmussen spelled out exactly the theological implications of Holmboe’s approach: “The voice of nature is heard … both as an inner impulse and as spokesman for a higher order. Certainty of this order is the stimulus of music, and to recreate it and mirror it is the highest goal. For this, faith is required, faith in meaning and context or, in Holmboe’s own words, ‘cosmos does not develop from chaos without a prior vision of cosmos.’” Holmboe’s words could come straight from one of Aquinas’s proofs for the existence of God. For Holmboe to make such a remark reveals both his metaphysical grounding and his breathtaking artistic reach. This man was not simply reaching for the stars, but for the constellations in which they move, and beyond. Holmboe strove to show us the cosmos, to play for us the music of the spheres.

Holmboe’s music is quite accessible but requires a great deal of concentration because it is highly contrapuntal. Its rich counterpoint reflects creation’s complexity. The simultaneity of unrelated strands of music in so much modern music (as in John Cage’s works) is no great accomplishment; relating them is. As Holmboe said, music has the power to enrich man “only when the music itself is a cosmos of coordinated powers, when it speaks to both feeling and thought, when chaos does exist, but [is] always overcome.”

In other words, chaos is not the problem; chaos is easy. Cosmos is the problem. Showing the coherence in its complexity, to say nothing of the reason for its existence, is the greatest intellectual and artistic challenge because it shares in the divine “prior vision of cosmos” that makes the cosmos possible. As Holmboe wrote, “In its purest form, [music] can be regarded as the expression of a perfect unity and conjures up a feeling of cosmic cohesion.” Arising from such complexity, this feeling of cohesion can be, he said, a “spiritual shock” for modern man.

Just as Holmboe, whose magnificent works are finally coming into currency, represents an unbroken line to the great Western musical tradition, John Adams is an exemplar of those indoctrinated in Schoenberg’s ideology who found their way out of it. Adams ultimately rejected his college lessons on Nietzsche’s “death of God” and the loss of tonality. Like Pythagoras, he “found that tonality was not just a stylistic phenomenon that came and went, but that it is really a natural acoustic phenomenon.” In total repudiation of Schoenberg, Adams went on to write a stunning symphony, entitled Harmonielehre (“Theory of Harmony”) that powerfully reconnects with the Western musical tradition. In this work, he wrote, “there is a sense of using key as a structural and psychological tool in building my work.” More importantly, Adams, explained, “the other shade of meaning in the title has to do with harmony in the larger sense, in the sense of spiritual and psychological harmony.”

Adam’s description of his symphony is explicitly in terms of spiritual health and sickness. He explains that “the entire [second] movement is a musical scenario about impotence and spiritual sickness; … it has to do with an existence without grace. And then in the third movement, grace appears for no reason at all … that’s the way grace is, the unmerited bestowal of blessing on man. The whole piece is a kind of allegory about that quest for grace.”

It is clear from Adams that the recovery of tonality and key structure is as closely related to spiritual recovery as its loss was related to spiritual loss. The destruction of tonality was thought to be historically necessary and therefore “determined.” It is no mistake that the recovery of tonality and its expressive powers should be accompanied by the notion of grace. The very possibility of grace, of the unmerited intervention of God’s love, destroys the ideology of historical determinism, whether it be expressed in music or in any other way. The possibility of grace fatally ruptures the self-enclosed world of “historically determined forces” and opens it up to the transcendent. That opening restores the freedom and full range of man’s creativity.

Cicero spoke of music as enabling man to return to the divine region, implying a place once lost to man. What is it, in and about music, that gives one an experience so outside of oneself that one can see reality anew, as if newborn in a strange but wonderful world? British composer John Tavener proposes an answer to this mystery in his artistic credo: “My goal is to recover one simple memory from which all art derives. The constant memory of the paradise from which we have fallen leads to the paradise which was promised to the repentant thief. The gentleness of our sleepy recollections promises something else. That which was once perceived as in a glass darkly, we shall see face to face.” We shall not only see; we shall hear, as well, the New Song.

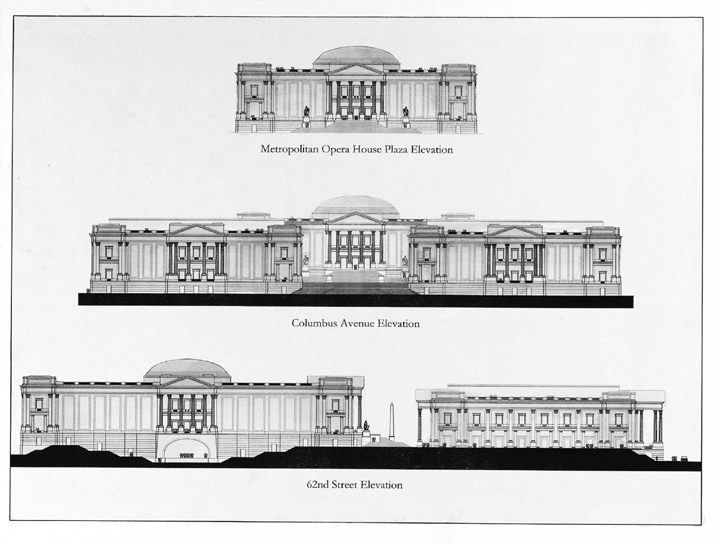

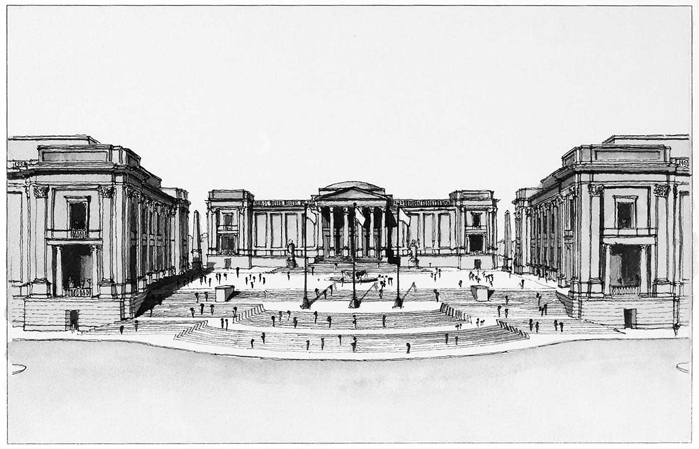

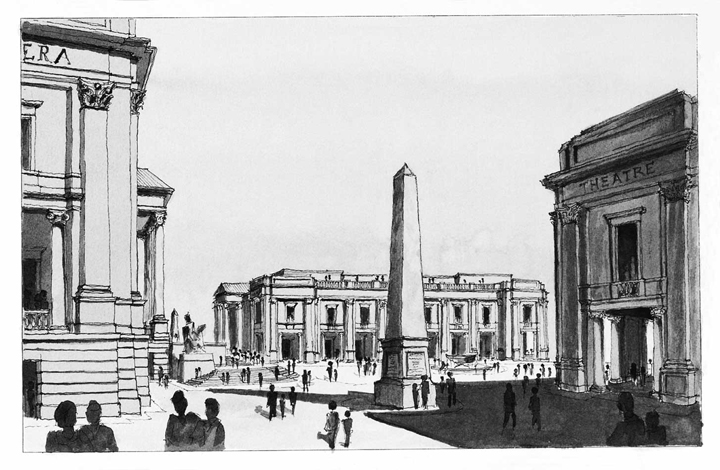

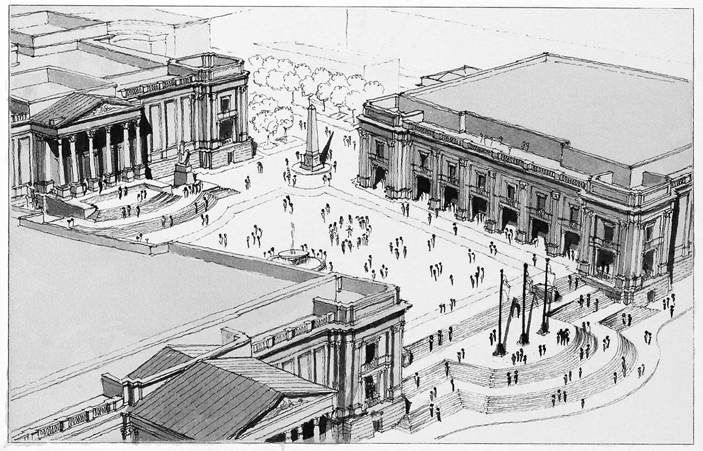

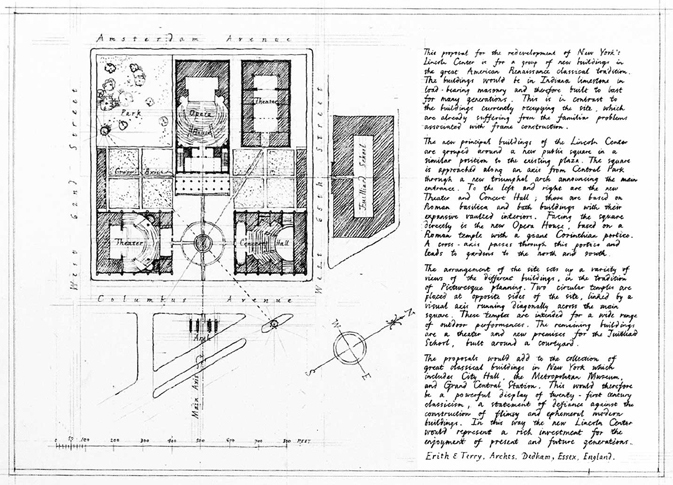

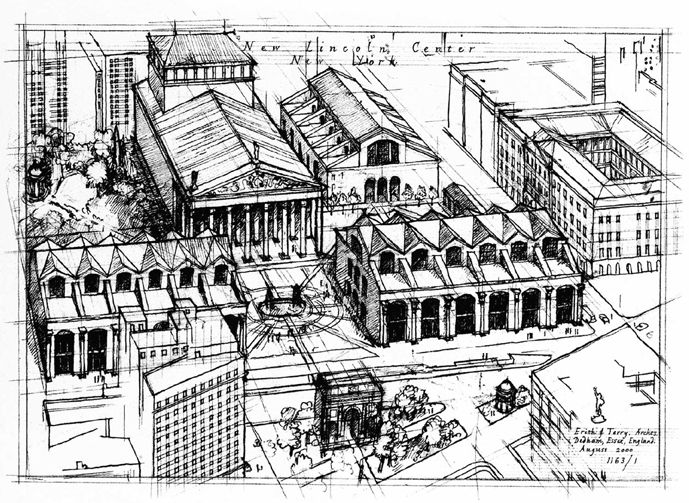

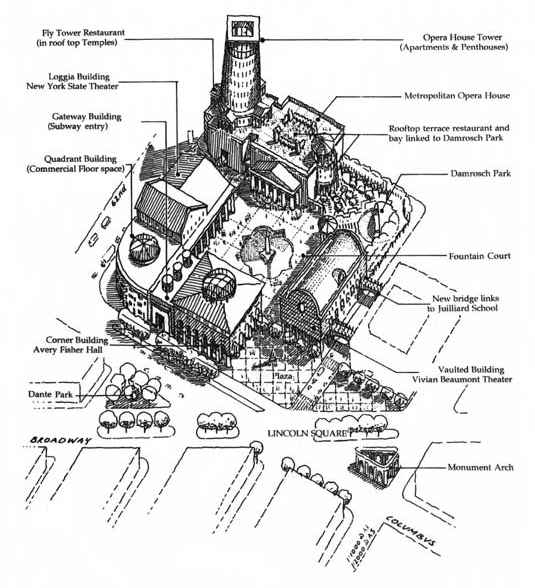

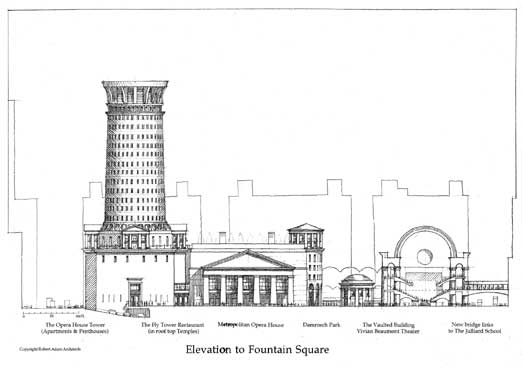

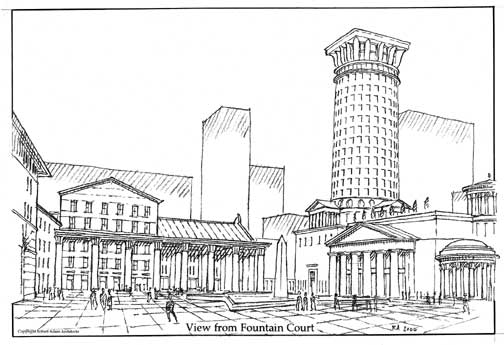

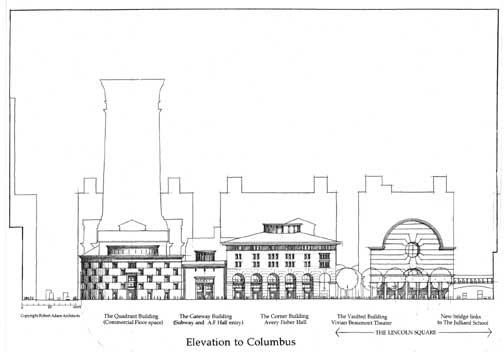

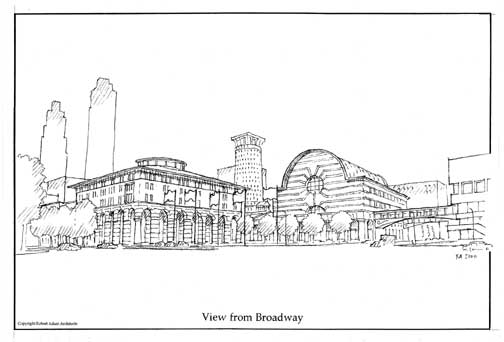

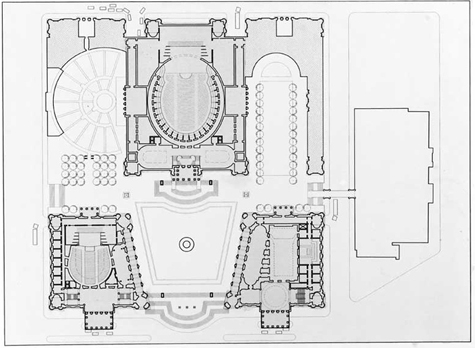

Diagonally across the new plaza, a distinctive new tower and a view of a massive Doric portico show the way to a large square at the heart of the block. In contrast to the public gesture of the plaza, this square is a pedestrian sanctuary from the clamorous roads outside. All the public buildings bound the new square. The Doric portico announces the entrance to the Metropolitan Opera House. A long Corinthian loggia flanks the south side of the court and leads to the New York State Theater. The Vivian Beaumont Theater and Avery Fisher Hall form the other sides of the square, and a rotunda gateway opens onto a relocated Damrosch Park.

Diagonally across the new plaza, a distinctive new tower and a view of a massive Doric portico show the way to a large square at the heart of the block. In contrast to the public gesture of the plaza, this square is a pedestrian sanctuary from the clamorous roads outside. All the public buildings bound the new square. The Doric portico announces the entrance to the Metropolitan Opera House. A long Corinthian loggia flanks the south side of the court and leads to the New York State Theater. The Vivian Beaumont Theater and Avery Fisher Hall form the other sides of the square, and a rotunda gateway opens onto a relocated Damrosch Park.

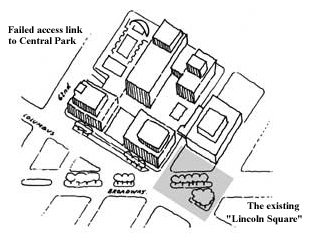

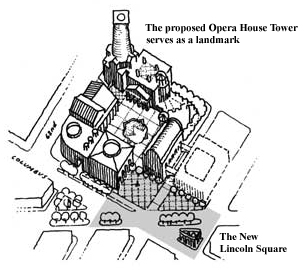

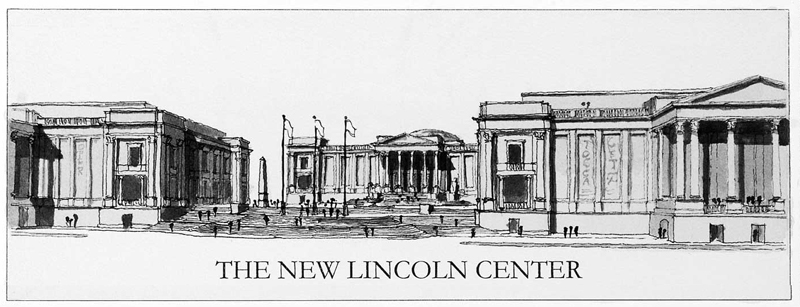

While it was noble that the designers loosely followed the urban form of Michelangelo’s Campidoglio in Rome, Michelangelo’s subtleties make Lincoln Center pale in comparison. Our proposal builds upon the legacy of Lincoln Center – or at least upon the Campidoglio model that inspired it.

While it was noble that the designers loosely followed the urban form of Michelangelo’s Campidoglio in Rome, Michelangelo’s subtleties make Lincoln Center pale in comparison. Our proposal builds upon the legacy of Lincoln Center – or at least upon the Campidoglio model that inspired it.