EDITOR’S NOTE: This book review is reprinted here with the gracious permission of

Modern Age where it first appeared in the Winter/Spring 2004 issue,

and in anticipation of the book’s new and expanded edition.

Surprised by Beauty: A Listener’s Guide to the Recovery of Modern Music, Robert R. Reilly, Washington, DC: Morley Books, 2002.

In his generous and beautifully written book, Robert Reilly leads us through the vast, largely unknown territory of twentieth-century music. The title recalls C. S. Lewis’s Surprised by Joy and the poem of the same name by William Wordsworth. The hero of the book is beauty. We are surprised by beauty – surprised because beauty in all its forms surpasses expectation and provokes wonder, and because the beautiful in music somehow managed not just to exist, but even to thrive in a century marked by brutal political ideologies and perverse intellectualism.

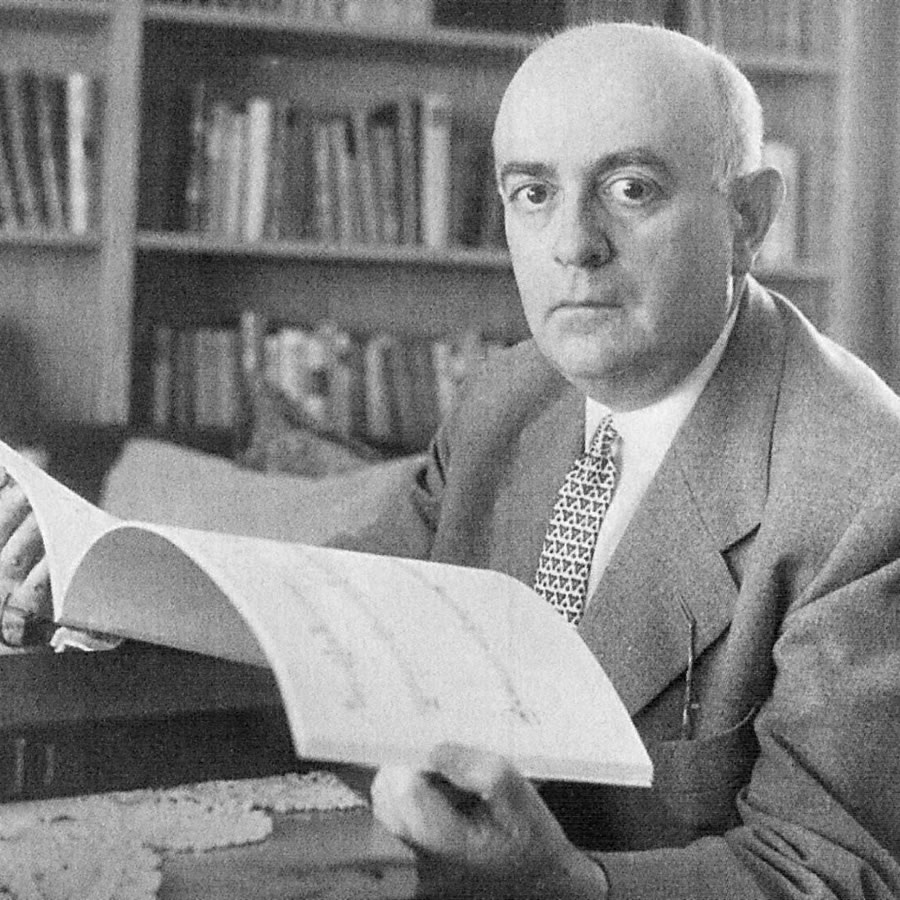

If the book has a hero, it also has its villain. This is serialism or the twelve-tone theory of Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951), who exerted a tremendous influence over the minds and works of many modern composers. Schoenberg advocated the emancipation of the dissonance. In a defining document from 1941, he wrote: “A style based on this premise treats dissonances like consonances and renounces a tonal center.”1 Instead of using the traditional diatonic order of whole steps and half steps (the source of the ancient Greek and medieval modes, and of the modern major scale), the serial composer takes as his governing principle a row or series comprising all twelve chromatic tones within the octave.

Schoenberg believed that the resources of tonality had been exhausted and that the times demanded a “New Music” – by which he meant “My Music.”2 He also said that he had been “cured of the delusion that the artist’s aim is to create beauty.” How wrong he was about the presumed exhaustion of tonality is overwhelmingly shown in the many and varied tonal composers we meet in Reilly’s book. As for the supposed disease from which Schoenberg had recovered – the pursuit of the beautiful – these same composers show us that beauty in the twentieth century was alive and well, no thanks to the Dr. Kevorkian of music. As the book’s subtitle indicates, Western classical music is enjoying a period of genuine recovery. It is rebounding from the “imposition of a totalitarian atonality.”3

The general reader need not fear that the topics in this book are too technical for him, or that he lacks sufficient musical knowledge, or familiarity with the works under discussion, to follow the author’s lead. Reilly brings his impressive knowledge of music to bear on the most human of our human experiences with a refreshing clarity and personal directness. He speaks from the fullness of his great love of music and infects the reader with the surprise he himself felt in the discovery of modern beauties.

The book has a simple, humane design. Its various chapters can be profitably read in any order. A series of essays in the truest sense of the word, it is a book that begs for browsing. The main part is a series of short chapters devoted to twentieth-century composers, thirty-nine in all, arranged in alphabetical order. It begins with the American John Adams and ends with the Brazilian Heitor Villa-Lobos. Each chapter has a memorable title that aptly sums up the composer. Samuel Barber is part of a chapter entitled “American Beauty”; Edmund Rubbra is “On the Road to Emmaus”; and Ralph Vaughan Williams is an example of “Cheerful Agnosticism.” The alphabetical ordering makes for a wild ride across Europe and the Americas. Or, to use what is perhaps a more fitting image, reading through the chapters is like walking along a beach and picking up one exotic shell after another. We are amazed to discover just how much beautiful music from so many countries washed up on the shore of the last century.

Without making music a mere product of its time, place, and circumstance, Reilly nevertheless also reminds us of the living human soil, the soil of suffering and affirmation, out of which great music grows. He relates deeply moving events in the personal lives of modern composers, events that shaped their compositions. We also get to hear their own often astonishing revelations about music as a response to life. If you have never heard a single work by any of these composers, be assured that you will want to hear them all by the time you finish reading this book.

The chapters have a twofold purpose: they are both contemplative and practical. In his contemplative mode, Reilly puts forth crisp, thought-provoking reflections on the power of music, and on the relation music has to God, nature, and the human spirit. As a practical guide, he offers knowledgeable advice about what to listen to and in what order. Every chapter contains a list of recommended works, including valuable information on recommended performances and recordings. I have followed Reilly’s guidance and have listened to many of the pieces he discusses. As a relative newcomer to modern music, I was grateful for whatever help I could get, and can report that this book, in its practical purpose, works. Readers of all musical backgrounds and tastes will profit from the accuracy of the descriptions and judgments, and the reliability of the musical advice. One does not merely read this book, or even re-read it: one lives with it and shares it with music-loving friends. One reads, then listens, then reads again, and again listens, each time listening with more acuity and pleasure, each time falling under the spell of a beauty that surprises.

In his Preface, Reilly reminds us that more than music is at stake in the debate over Schoenberg’s theories and compositions – much more. The clearest crisis of the twentieth century, we are told, is the loss of faith and spirituality. Schoenberg’s dodecaphony and the rejection of tonal hierarchies were the musical outgrowth of this deeper pathology. The connection between atheism and atonality was summed up by the American composer John Adams, who said, “I learned in college that tonality died somewhere around the time that Nietzsche’s God died, and I believed it.”

The metaphysical implications of atonality are at the center of two concise essays that frame the journey through modern composers: “Is Music Sacred?” and “Recovering the Sacred in Music.” In the first essay, after a pointed discussion of the Pythagorean discovery that linked music with reason and nature, and the resultant idea of a “music of the spheres,” Reilly points to Saint Clement of Alexandria’s view of Christ as the “New Song,” and of the harmonious bond between “this great world” and “the little world of man.” Reilly then describes the falling away from these inspired ideas. He shows us not only what Schoenberg’s theory asserted, or rather denied, but also the cultivation of chaos (in the music of John Cage) that inevitably followed the denial of natural order.

The second essay depicts Schoenberg as a false Moses, who “led his followers into, rather than out of, the desert.” Speaking from the perspective of his deeply held Roman Catholic faith, Reilly offers an interpretation of how Schoenberg’s lack of faith rendered him incapable of finishing his opera, Moses and Aron. We also hear a moving account of three modern composers of demanding sacred music: Górecki, Pärt, and Tavener. Their most urgent message – the antidote to modern noise and restlessness – is Be still. Here Reilly defends the works of these composers against the charge that they wrote nothing more than “feel good mysticism.” The story of Górecki, whose music was a response to what Poland suffered under the Nazi and the Communist regimes, is harrowing and sublime. It shows us that modern man, with eyes wide open to the horrors of his age, need not yield his creative spirit to the mere expression of those horrors.

As a sort of appendix, there is a concluding section called “Talking with the Composers.” Here, Reilly relates fascinating conversations he has had with the writer and conductor Robert Craft (who conducted music by both Stravinsky and Schoenberg), and with the composers David Diamond, Gian Carlo Menotti, Einojuhani Rautavaara, George Rochberg, and Carl Rütti.

Especially revealing is the conversation with Rochberg, “the dean of the twelve-tone school of composition in the United States and the first to turn against it.” Rochberg gives an extraordinary insider’s perspective on the fatal limits of serialism. He complains of the loss of musical punctuation, by which the composer tries to capture meaning and expressivity: “What I finally realized was that there were no cadences, that you couldn’t come to a natural pause, that you couldn’t write a musical comma, colon, semicolon, dash for dramatic, expressive purposes or to enclose a thought.” Even more striking, he notes how the series of twelve-tones, once selected, kills off the possibility for openness and freedom: “Everything is constantly looping back on itself.” This is extremely interesting because, in the classical tradition, circularity was the hallmark of the divine, the sign of perfection and even of freedom.

The very diatonic order that Schoenberg rejected is itself circular or periodic – a fact most obviously present in the major scale. But the major scale has a natural directedness, while the twelve-tone row does not. Diatonic music is only apparently restrictive in its circularity: in fact, it promotes infinite tonal adventure. That is because, as most people can hear, it has a natural sounding flow, a freedom most evident in Gregorian chant. Schoenberg’s circles are, then, the perversion of natural circles. They do not liberate but imprison. They are like the circles of Dante’s Hell – where, we recall, there is no music but only noise. In Rochberg’s exposé, we come to realize the unmitigated tyranny of twelve-tone composition. We see how the creator of musical value is ultimately the slave of his tone-row creations. Serialism thus becomes a parable for modern times, a cautionary tale about the rage for autonomy.

Schoenberg did not just reject tonality: he denied that tonality existed “in Nature.” His desire was “to demote the metaphysical status of Nature.” The rage for autonomy must always be at odds with nature. Nature sets a permanent, insuperable limit to the human will. One cannot change what is. And if, in addition, what is is hierarchical and normative, as the classical tradition asserted, then nature is not just insuperable but authoritative: it is not only the thing you cannot change but also the thing you ought not change, the good. It is Schoenberg’s metaphysical negativity, the denial not of the mere use but of the naturalness of tonality, that makes his ideological transformation of music so devastating and, to the proponents of radical autonomy, so attractive.

As we see from the opening essay, nature is the beautifully ordered whole of all things, what the ancient Greeks called a cosmos.4 Before Nietzsche’s death of God there was the death of cosmos – death in the sense that, with very few exceptions (Kepler and Leibniz), cosmos came to be what C. S. Lewis called a discarded image, an idea that had ceased to govern and inspire the European mind. Many busy hands contributed to this death, and it is important to identify the executioners if we are to appreciate the full force of the recovery of nature in its traditional sense.

The first step was the nominalism of William of Ockham. This reductionist theory effectively paved the way for modern skepticism regarding essences and universals, that is, natures. Then there was the formidable new science of Bacon and Descartes, which rejected final causes and natural placement in favor of mastery and possession: nature was something to be engineered rather than imitated. But it was Pascal who administered the coup de grace in the death of cosmos. With Blaise Pascal, man was no longer “placed” within an ordered whole. Instead, he was trapped between the infinitely little and the infinitely big. Nature was not a cosmos but an infinite universe inspiring fear, not love: “The eternal silence of these infinite spaces fill me with dread.”5 Pascal’s emotive imagery did what Cartesian science could not: make the denial of cosmos seem profound.

One of the biggest surprises in Reilly’s book is the sheer number of modern composers who have devoted themselves to nature in the older, classical sense. Most striking in this respect are the Scandinavian composers. When Sibelius (1865–1957), Nielsen (1865–1931), and Holmboe (1909–1996) respond to nature, they are not filled with terror. Nor do they hear eternal silences. For them the natural world is just as spacious and awesome as it was for Pascal, but it is filled with music rather than silence. The music of Sibelius is “a revelation of nature in all of its solitary majesty and portentousness.” Nielsen defies the moribund expression of angst and ennui with music that “can exactly express the concept of Life from its most elementary form of utterance to the highest spiritual ecstasy.” And Holmboe, the most overtly cosmic of them all, affirms that music enriches us only when it is “a cosmos of coordinated powers, when it speaks to both feeling and thought, when chaos does exist but [is] always overcome.”6

Nature, for Reilly, is not the highest point of our journey, either through music or through life. As we read in the book’s opening essay, “With Christianity the divine region becomes both transcendent and personal because Logos is Christ. The new goal of music is to make the transcendent perceptible.” The transcendent is that which goes beyond nature and human reason. It is the supernatural realm of grace. This higher realm of grace, as Aquinas so beautifully puts it, “does not destroy nature but brings it to perfection.”7 The beautiful in music, far from being cancelled in the move from nature to spirit, now finds its highest vocation. Like Dante’s Beatrice, it is the grace-like shining forth of the transcendent within the natural, the eternal within the temporal. In this transition from beauteous nature to transcendent grace, the reader’s odyssey through modern music becomes a pilgrimage. We hear the most astounding claim about music and transcendence from Welsh composer William Mathias. Defying the usual view that music as the temporal art par excellence is delimited by temporality, Mathias is reported to have said, “Music is the art most completely placed to express the triumph of Christ’s victory over death – since it is concerned in essence with the destruction of time.”

Some of the greatest beauties we discover in our musical journey through the last century are works by Christian composers. Reilly is eager, however, to acknowledge the inspired products of agnostics like Vaughan Williams and Gerald Finzi. Indeed, the agnostic lovers of beauty are interesting precisely because they offer an example of man’s continual hunger for spiritual food. The most memorable entry in the lists of the faithful is Frank Martin. This is the Calvinist composer whose religious works offer a “Guide to the Liturgical Year.” Martin is the exact opposite of Schoenberg. One reason is that this highly sophisticated Swiss composer dared to write simple, even childlike music “that goes directly to the heart.” Another is that he pursued anonymity to an amazing degree: “While listening to his religious music, one never thinks of Martin.” This is a composer you cannot imagine talking about “My Music.”

More than anything else, Surprised by Beauty makes us glad. We rejoice that there are still those for whom music has a spiritual meaning, that a ferocious love of beauty is still alive in the great works of modern composers, and that this love, to quote from the title of Nielsen’s Fourth Symphony, seems to be inextinguishable.

Endnotes

1 “Composition with Twelve Tones,” in Style and Idea, Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg, Berkeley, 1975 [Reilly, 217]. Whereas tonal music is hierarchical, twelve-tone music is egalitarian: all the tones in the twelve-tone row must be given equal emphasis, “thus depriving one single tone of the privilege of supremacy.” (Reilly, 246)

2 Schoenberg’s preoccupation with himself is revealed in the titles to some of his writings: “The Young and I” (1923), “My Blind Alley” (1926), “My Public” (1930), “New Music: My Music” (c. 1930).

3 Schoenberg disapproved of the term atonal. He said that calling his music atonal was like calling flying the art of not falling, or swimming the art of not drowning. In the end, however, he resigns himself to the term, saying: “in a short while linguistic conscience will have so dulled to this expression that it will provide a pillow, soft as paradise, on which to rest” (Style and Idea [210]).

4 An essential feature of cosmos is the differentiation of things according to kind. The diatonic order, as opposed to the twelve-tone bag of elements, preserves the kind-character of the different intervals generated from the order. Experience informs us that the perfect fifth, for example, is different in kind from the major third. Twelve-tone music renders this difference in kind meaningless. It would have us live in a world without character.

5 The thought of Pascal and his eternal silences brings to mind the amazing poem by Baudelaire, Rêve Parisien, in which the poet fantasizes about a purely visual world : Tout pour l’oeil, rien pour les oreilles! It must be noted that for Pascal and Baudelaire, a world without sound or music, while terrifying, is also strangely attractive.

6 Jacques Maritain helps us steer clear of thinking that the composer’s love of nature is a slavish act of imitation. He writes: “Artistic creation does not copy God’s creation, it continues it …. Nature is essentially of concern to the artist only because it is a derivation of the divine art in things, ratio artis divinae indita rebus. The artist, whether he knows it or not, consults God in looking at things” (Art and Scholasticism, New York, 1962 [60–61].

7 Summa Theologica, First Part, Question 1, Article 8.