So, why would a research institute focused on the future of live classical music be here with you in Seaside today to talk about architecture and urbanism? The most obvious answer relates to the fact that orchestras have to have concert halls: architecture and urbanism address the questions of Where and How we build them. Those are some pretty big and important questions, and would themselves be enough to bring us together here today. But our interest in architecture and urbanism actually goes much deeper than that – and it’s what brings us specifically here and not somewhere else – like, say, New York or Atlanta.

We certainly didn’t know, when we began to study the problems of orchestras and their concert halls, that our work would lead us here. But we knew for sure that there was something wrong and that orchestras are fighting uphill because of it. And if our orchestras are struggling to keep a foothold in our communities, our communities are struggling to keep music around, too. Perhaps the fight is most visible in our schools, where music education is always either endangered or extinct. But we also see it every year in the towns across America that lose their orchestras to insolvency and neglect. Something is out of balance and all the usual answers and solutions offered to fix the problem just aren’t working.

So we began to dig deeper. We began to question not just the usual answers, but the usual questions, too. That led us to some surprising places, and we started to notice something remarkable: that the challenges facing orchestras and classical music today are not unique to them! In fact, we have a lot to learn from a lot of other fields and disciplines when we look at them in fresh new ways. Some of the lessons we find are cautionary tales, and some are important comeback stories that inspire us with hope and a real vision for the future. The stories of modern architecture and urbanism are both of these things.

If those of us in the world of classical music will look closely, we will see in the mistakes and failures of modern architecture and urban planning the reflection of our own mistakes – the ones we are still enthusiastically making every day, without any thought to the idea that they might be, in the end, mistakes. And they are significant errors because they represent our fundamental assumptions about human nature, our understanding of the ways we relate to our built and natural environments, and our attitudes towards tradition and the past. We compound our problems with every decision we base on these misunderstandings.

On the other hand, the spectacular successes of New Urbanism and the revival of classical architecture provide us with a real model of recovery. And this is perhaps the most important and deepest of lessons to be mined here: the triumph of places like Seaside teach us something very important about human nature and values, about what changes, and about what endures. And we hope that together this weekend we can all begin to hash out the place for music in our communities and how best to build them together.

But before we get to the part about Where and How we build concert halls, let’s take a moment to consider the Why. What is the “end” of the concert hall, the ultimate purpose for which it exists – the telos, if you will? As you can imagine, that’s a very important place to start. The Where and How will have to relate to the Why. And we have broken that answer into three components to present you with today.

The Telos of the Concert Hall

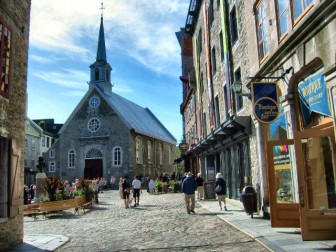

Firstly, the hall is a home for classical music and for the orchestra that lives there. This part is easy to understand. The concert hall is the oikos for classical music in any community. It is where the orchestra resides – where it makes its home – and the place from which it goes out to meet its neighbors. It is the physical presence of classical music that we are obliged to encounter daily, standing there, come what may, shoulder to shoulder amongst its neighbors as a member of our community. It is the place where the orchestra welcomes and entertains its guests and friends with the very best hospitality it can muster. The concert hall, in short, takes part in that cooperative effort of place-making that makes a community a “home” worth loving – that inspires in us what Roger Scruton calls oikophilia.

The concert hall also represents a physical connection to the classical tradition that calls it home. In the same way that our homes come to reflect us, our values, and our lifestyles, the concert hall should celebrate the history and the values from which the tradition and the great canon of music, constantly celebrated and performed inside it, arose. It must invite us to become familiar with, to know, to understand, to respect, and to love that tradition. And that’s more important than you might think – and certainly more important than many of today’s orchestras apparently think – because our orchestras depend not on the novelty-seekers that wander through their doors from time to time – or even in hordes if we’re lucky. Nor do they get by on the grants and funds set aside by government and civic-minded foundations to support adventurous forays in the arts. No, orchestras rely almost entirely on the donations, large and small, of the individuals in their communities who come to love them and the classical repertoire they are so highly qualified to present.

In today’s exceedingly troubled world, it can be a difficult thing to convince even those whose love of classical music is deeply rooted and unshakeable to dedicate a significant portion of their income to support their community’s orchestra. There are a myriad of other causes clamoring for their attention, many of which take direct aim at classical traditions. What happens if the concert hall itself repudiates or denounces the very thing the orchestra will then have to convince its guests to support once they’ve come inside? Talk about shooting ourselves in the foot!

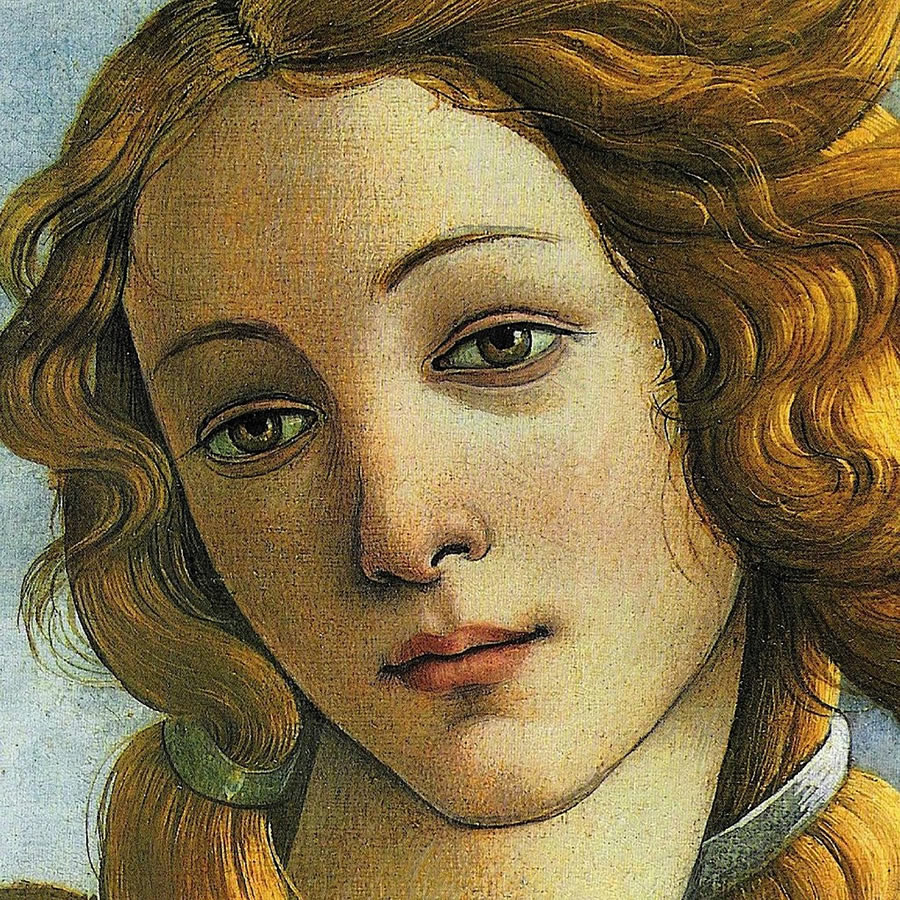

So the concert hall must be a connection to the community in which it lives and a connection to the classical tradition which lives in it, but there is another important point to make about the telos of concert halls. And this one might be the most interesting of all: the concert hall is a place set apart, not unlike a church or a cathedral, for the encounter of something that transcends this world. And like it was for so many souls across so many generations who wore the paths to our cathedrals and churches and kneeled to pray inside them, the experience to be encountered inside the concert hall, if it is to be fully appreciated, must be approached in silence and with an attitude of maximum receptivity. As Sir Roger explains it,

You entered both the church and the concert hall from the world of business, laying aside your everyday concerns and preparing to be addressed by the silence. You came in an attitude of readiness, not to do something, but to receive something. In both places you were confronted with a mystery, something that happened without a real explanation, and which must be contemplated for the thing that it is. The silence is received as a preparation, a lustration, in which the audience prepares itself for an act of spiritual refreshment.1

And in the concert hall we all sit facing, as we do the altar in church, the same point in space in which, nevertheless, the thing we ultimately encounter appears not so much as a physical presence, but as something that moves inside our very souls.

This experience – the possibility of this kind of encounter, which connects us to each other in the present by connecting us to community, to each other in the past by connecting us with tradition, and to each other in the future by connecting us to that which is beyond this world – this is what we stand to lose if we get the telos wrong. But it’s also what we stand to lose if we get the architecture and the urbanism wrong. And too often we do just that. Too many orchestras have been following modern architecture and urbanism down a dead-end street. What do we mean by that? Well, let’s look at some of the mistakes of modern architecture and urbanism. Most of these mistakes will be familiar to those of you who work, live, and play in Seaside, but it has yet to dawn on the classical music world that these even are mistakes.

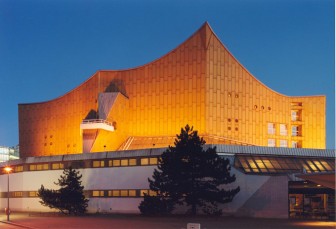

The Mistakes of Modern Architecture

The first is a problem of scale. The use of machines to assemble buildings has led architects and developers to dramatically over-scale them. This is true of the office buildings, shopping malls, civic plazas, and towers full of apartments and condos that mar our cities and send our suburbs sprawling every which way. It’s also true of concert halls. And often the scaling error spills over into vast concrete plazas and parking garages that become like desert wastelands that must be traversed before the concertgoer even gets to the front door of the hall. We feel like ants crawling across the pavement to this thing looming far above us. While all this is meant to communicate that the orchestra living there is both modern and impressive, it actually leaves us with the feeling that the orchestra does not live side-by-side with us as a neighbor would, but imposes itself on us as some cold, tyrannical machine, quite probably administered by Vogons. The orchestra is left to cast desperately about for some way to convince the community that it is in fact relevant to them while all day, every day, its own home is broadcasting unmistakably and emphatically that it’s not at all.

The next mistake, in which orchestras are thoroughly caught up (and not just when it comes to their concert halls), is the mythology of “progress.” In architecture the most basic manifestation of this idea is the use of synthetic materials just because they exist – and represent “progress” – to create an architecture that we think is, therefore, “of our time.” But the use of unconventional materials (or else the unconventional use of materials) creates new problems that have to be solved – often at great cost in both resources and finances. We end up, for instance, with need for expansion joints and “permeable” pavement. And the usable life of these “progressive” buildings becomes shockingly short. According to Quinlan Terry, a

recent American report on the life of steel and glass high rise buildings put their useful life at twenty-five years. They may last a little longer, but after 40 years or so they are often demolished, the materials cannot be recycled so they are dumped in a landfill site and the laborious process of reconstruction begins again at phenomenal financial and environmental cost. So Modern construction as a means of providing a permanent home or place of work has been a failure from conception to the grave, and more seriously, it expresses a culture that has no history and no future.2

(Which of course also speaks eloquently to one of our earlier observations about the ends, or telos, of the concert hall.) The cost to maintain these “progressive halls,” to heat them and cool them, and then to tear them down and rebuild them again soars far beyond anything that should be considered responsible or acceptable – and makes the whole project incredibly and tragically wasteful. The progressive concert hall becomes another manifestation of our disposable consumer culture. And as you know, we cannot forever maintain that way of life.

If we think that technology has allowed us to circumvent the best ideas about materials and techniques handed down to us by thousands of years of craftsmen, we also think it allows us to trump localism in our building and planning. We’re no longer restricted by soil, climate, altitude, or local resources. And so what we build in the name of “progress” is not only certain to be less suited to its environment in terms of efficiency, we can also see that it begins to look the same everywhere. Faceless walls of glass, steel, and concrete wherever we go. In the vacant reflections on those enormous glass walls, we lose the particulars and the context that make a place feel like home. Architecture as a triumph of technology becomes just a display of power and reminds us only of the ever-present triumph of the global capitalist – unrooted, wasteful, and drunk on oil.

But wait, the fantastical modern concert hall is not really about any of those things. The building materials are just the medium. The architecture of the concert hall is about artistic expression! Does that sound familiar?

Misunderstanding architecture as primarily some kind of artistic/ideological expression rather than as an art of building well is another mistake. This is the affliction of many “starchitects” and the planners who employ them. And it’s the same kind of mistake that plagues modern art and modern musical composition as well: it’s not art as skill but art as concept. And it ends up being art that has to be explained in order for us to even recognize it as art. I’m going to give you an example here, which you might know because it’s quite famous – and, honestly, because it’s so absurd that once you’ve heard it, you probably won’t forget it:

An Oak Tree is a work of art created by Michael Craig-Martin in 1973, and is now exhibited with the accompanying text, originally issued as a leaflet. The text is in red print on white; the object is a French Duralex glass, which contains water to a level stipulated by the artist and which is located on a glass shelf, whose ideal height is 253 centimeters with matte grey-painted brackets screwed to the wall. The text is behind glass and is fixed to the wall with four bolts. Craig-Martin has stressed that the components should maintain a pristine appearance and in the event of deterioration, the brackets should be re-sprayed and the glass and shelf even replaced. The text contains a semiotic argument, in the form of questions and answers, which explain that it is not a glass of water, but “a full-grown oak tree,” created “without altering the accidents of the glass of water.” The text defines accidents as “The colour, feel, weight, size…”. The text includes the statement “It’s not a symbol. I have changed the physical substance of the glass of water into that of an oak tree. I didn’t change its appearance. The actual oak tree is physically present, but in the form of a glass of water.” and “It would no longer be accurate to call it a glass of water. One could call it anything one wished but that would not alter the fact that it is an oak tree.”3

Really, the gimmick isn’t even clever. But, even if we grant that art as concept or gimmick might be fine for things like painting or sculptures – or whatever you’d call “An Oak Tree” – it presents us with some serious problems in the case of buildings, which must actually be used and lived in. It’s not enough for us just to call a thing a roof or a door or a lintel, it must actually be one – it must perform all the functions assigned to it as completely and perfectly as possible. Similarly, if we had to rely on this thing we’re told to call “An Oak Tree” to be an oak tree, to perform any of the functions of an oak tree – say, for shade, a windbreak, or a producer of acorns – we’d be in big trouble.

The very first function of a door, for example, is to be recognizable as one. The door is the thing we aim for on the face of any building, isn’t it? If we can’t easily find or identify the door, the rest of the building might as well be rubbish. A concert hall, too, at the very least has to be recognizable as one. We have to know where to go to find the symphony concert and then how to get into the hall once we’ve identified it. So if you build a gimmick for a concert hall and it looks for all intents and purposes like a parking deck or a giant can-opener, you’re going to have to put some effort into getting people inside – maybe you’ll have to put up one of those signs like the “Oak Tree” fellow did to explain the joke. And let’s hope that everyone appreciates the joke, because we all know the alternative is to acknowledge that one is “uncultured.” A hall like that is an ultimatum and not a good starting point for a relationship with the members of a community who actually make it a point to seek out culture.

And yet this is exactly what many orchestras are doing for the sake of architecture as “artistic expression” – and it’s compounded by the misapplication of the idea of “progress” to art. But that is a subject worthy of its own entire conference, so I’ll leave it there to be brought up another day. And I will point out only that, ultimately, this mistake is grounded in the original problem of misunderstanding the telos of the concert hall. It is not to be an artistic interpretation of a concert hall, it is to be a concert hall – which is to say it is to perform all the functions of home for the orchestra that we pointed out earlier.

The Mistakes of Modern Urbanism

How about the mistakes of modern urbanism? Again, probably something very familiar to those of you who have invested in the correction, a fine example of which we are fortunate enough to be standing in today. But let’s point these mistakes out for the sake of the classical music world who probably hasn’t even thought about them, even though the city is the orchestra’s natural habitat.

First we might point out the habit of growing by building out and up rather than by the replication of a small and entire unit – like the fractal way in which Nature grows. Quite unnaturally, our towers get higher and our cities swell in concentric circles. A new beltway encircles the old beltway and swallows up the urban sprawl between in an ever-widening blob. Then the center of the circle, the bull’s eye, growing ever more distant from its life-supply, starts to die out and becomes an empty jumble of desiccated bones leaning against the sky – those skyscrapers, or vertical cul-de-sacs as Léon Krier describes them, are abandoned for the sad strip-malls and Prozac-inducing business parks of the sprawling suburbs. I paint a depressing picture, but we all know it well.

Orchestras are making this mistake, too. Their concert halls are turning into musical mega-complexes, gobbling up multiple halls, recital spaces, and music schools into one over-scaled “machine for music,” instead of distributing smaller halls and venues and schools throughout many smaller urban centers and neighborhoods. Often they are built in the center of the city before it is abandoned, or else put there after it has emptied out in a last ditch effort to bring everyone back to the gutted downtown.

An increasingly popular idea is to put the hall in a designated Arts and Culture District. This should remind us of another great mistake of modern urban planning: the single use district or zone. Like the shopping district, the financial district, the business district, or even the wallowing housing tracts of our suburbs, the arts and culture district creates another kind of cul-de-sac. People come into them only if they’ve already made plans to consume some culture – or else entirely by accident, in which case they will probably just want to get themselves turned around and back out again. Which means that they do not encounter the concert hall as a part of the normal course of their everyday life and movements. And yet music should be a part of our normal, everyday lives. So we’re doing something wrong.

The concert hall should be there in our midst to remind us of this great thing that is always in our presence, always part of our history, our culture, and our being, and always inviting us in to partake of it. If the hall can’t do that from the corner we’ve assigned it to, then our orchestras must constantly be elbowing their way into our attentions elsewhere in our busy world. And it’s a hard task for them to remind us about the importance of music in our lives from the fringes of it. It’s a hard task to get us to focus on what’s going on in our peripheral vision and we might argue that this is a big part of the reason that music is disappearing from so many of our schools and communities. It became invisible long before it disappeared.

The Good News

Well, so far it’s been all bad news. But the real reason we’re here in Seaside with you this weekend is to talk about the good news! The good news is that architecture and urbanism are righting themselves. And both the revival of classical architecture and the tremendous successes of New Urbanism provide a model of recovery for classical music. We’re here to tell them about it.

It’s enormously encouraging, even if it’s not all that surprising, to see the impressive professional achievements and architectural accomplishments – and, indeed, the growing number – of classical architects both here and abroad. I’m thinking of men like Quinlan Terry, Allan Greenberg, Robert Adam, and John Simpson. Organizations like the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art, which started out as “a small group of determined activists in New York”4 not 50 years ago, are popping up all over the country now – and thriving with actively growing and enthusiastic memberships. Architects, students, and “lay” people alike are lining up to learn how to draw the orders. Imagine that.

Three decades ago Notre Dame University began the difficult work of rebuilding an architectural education program on the principles and disciplines of classicism. That work is paying off handsomely now as their graduates are some of the most sought-after young architects to enter the field each year. And other schools are now following in the path Notre Dame bravely forged: the College of Charleston, South Carolina; the University of Colorado at Denver, and The Catholic University of America in Washington, DC are all becoming centers for classicism and tradition, eagerly pursued by a hungry new crop of students every year. Indeed, we are seeing in classical architecture something very like the current renaissance in realist artwork that has aspiring artists flocking to ateliers to study – painstakingly and for many years – under the few painters and sculptors who kept the traditions, skills, and techniques of the masters alive while the rest of the world went cuckoo for cocoa puffs.

It’s perhaps our greatest joy at the Future Symphony Institute, however, to see the triumph of the work of David M. Schwarz and his team of architects, who are building – for the orchestras who have figured a thing or two out already – some of the most beautiful and astonishingly appropriate concert halls that we’ve seen in more than a century. From his renovation and expansion of the Cleveland Orchestra’s famed Severance Hall to the new buildings he designed for Las Vegas; Carmel, Indiana; Fort Worth; Charleston; and Nashville, Schwarz’s concert halls are masterpieces and fully worthy of the priceless tradition, represented by the canon of classical music, which will call these halls “home.” We’re honored to have Gregory Hoss, president of that team of architects, here with us this weekend; and I encourage you to check out these halls if you’re not familiar with them yet. We also have with us Cliff Gayley, of William Rawn and Associates, who did the remarkable and intimate Ozawa Hall at Tanglewood and Green Music Center in Sonoma, not to mention Strathmore Music Center, where I am lucky to perform every week.

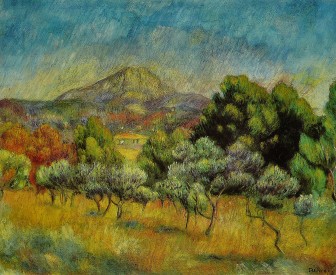

And urbanism, too, is showing signs of recovery. But it’s clearly New Urbanism that is pointing the way. This is of course the reason why we are so excited to be here in Seaside and nowhere else this weekend. I don’t know if even the visionary founder of Seaside, Robert Davis, or his team of planners and architects really knew just how successful their experiment was going to be. I have to wonder if maybe we’re fortunate that they did not because there was no greed in their motivations – and that fact has helped to save Seaside from the sins that ravage our cities and suburbs. No, Seaside was born of an honest and modest accounting of human nature and the habits of happy human settlement. And it has become a beacon and a model for towns far and wide. Communities inspired by it and founded on New Urbanist principles are springing up everywhere from the Kentlands in Maryland – not far from where I live – to Poundbury in England and Cayalá in Guatemala. And they are all, to the extent that they understand and embody the philosophy of New Urbanism, wildly successful.

New Urbanism is making its way into the often stagnant backwaters of higher education, too, with the University of Miami and Andrews University taking the lead. And while the Congress for New Urbanism is the most visible and important of the organizations formed to promote its principles, we are seeing a vigorous blooming of grassroots efforts – by groups such as the Alliance for a Human-Scale City in New York – to save our towns, neighborhoods, and cities from the devastating effects of poor planning and bad architecture. In the professional arena, New Urbanist design firms and developers are cropping up all over the nation.

And that’s because New Urbanism has given everyone – from citizens to developers to city officials – not only a reason to believe they can build something better, but also the blueprints with which to build it. It is waking us up to the memory that our cities were not always blighted canyons and our neighborhoods were once abuzz with authentic interactions between neighbors. People are investing – more importantly than money – love in their communities. It is a sign of that oikophilia I mentioned at the outset when people insist that their community be a place that is lovable: that it be human in scale, local in context, and neighborly in manner.

Classical music must find its place in this kind of love – love of home, of community, of neighbor, and of the culture that binds all these things together. In all but the most exceptional cases, our orchestras won’t survive if they don’t get this part right. They depend on love and a connection to their communities – a recognition of their relevance and of their membership in the project of placemaking – to survive. What’s more, they depend on all the small towns across our nation – and even around the world – to provide kids with the opportunity to join the marching band and the youth orchestra, to learn to play the recorder in elementary school and the clarinet in high school, to sneak into a concert hall and be blown away by Beethoven’s symphonies and Mozart’s operas (like I did as a kid) – in short, the opportunity to become our next generation of orchestral musicians who’ll go on to play some of the most astounding music ever written in some of the greatest halls ever built.

The classical music world needs to learn the lessons that Seaside has to offer – and not simply those about walkability and mixed-use, but the deeper lessons behind those, too. Because the greatest success of Seaside is what it gets right about human nature, about our relationships to each other and our built and natural environments, and about our enduring values. I believe wholeheartedly that in every community there is a place for music. And that music is a part of placemaking.

Endnotes

1 Scruton, Sir Roger. “Tonality Now: Finding a Groove.” Future Symphony Institute. Accessed 7 March 2018.

2 Terry, Quinlan. “Why Traditional Architecture Matters to our Culture.” Traditional Britain Group. Accessed 7 March 2018.

3 Wikipedia entry: “An Oak Tree.” Accessed 24 February 2018.

4 The Institute of Classical Architecture & Art: About. Accessed 2 March 2018.

Postscript

Dhiru Thadani and his team insist that this Chicken Biryani they made for us on Saturday night is also, in fact, an Oak Tree: the best oak tree we ever ate.