EDITOR’S NOTE: This essay is reprinted here with the gracious permission of City Journal, who first published it in the Summer 2010 issue of their magazine.

Anyone inclined to lament the state of classical music today should read Hector Berlioz’s Memoires. As the maverick French composer tours mid-nineteenth-century Europe conducting his revolutionary works, he encounters orchestras unable to play in tune and conductors who can’t read scores. A Paris premiere of a Berlioz cantata fizzles when a missed cue sets off a chain reaction of paralyzed silence throughout the entire sorry band. Most infuriating to this champion of artistic integrity, publishers and conductors routinely bastardize the scores of Mozart, Beethoven, and other titans, conforming them to their own allegedly superior musical understanding or to the narrow taste of the public.

Berlioz’s exuberant tales of musical triumph and defeat constitute the most captivating chronicle of artistic passion ever written. They also lead to the conclusion that, in many respects, we live in a golden age of classical music. Such an observation defies received wisdom, which seizes on every symphony budget deficit to herald classical music’s imminent demise. But this declinist perspective ignores the more significant reality of our time: never before has so much great music been available to so many people, performed at levels of artistry that would have astounded Berlioz and his peers. Students flock to conservatories and graduate with skills once possessed only by a few virtuosi. More people listen to classical music today, and more money gets spent on producing and disseminating it, than ever before. Respect for a composer’s intentions, for which Berlioz fought so heroically, is now an article of faith among musicians and publishers alike.

True, the tidal wave of creation that generated the masterpieces we so magnificently perform is spent; we’re left to scavenge the marvels that it cast up. The musical language that united Bach, Schubert, Mahler, and Prokofiev finally dissolved into inaccessible atonalism by the mid-twentieth century; subsequent efforts to reconstitute it have yet to gather the momentum of the past. But in recompense for living in an age of musical re-creation, we occupy a vast musical universe, far larger than the one that surrounded a nineteenth-century resident of Paris or Vienna. We can hear the beauty in the poignant chromaticism of Gesualdo and the mysterious silences of C.P.E. Bach, no less than in the by now more familiar cadences of Beethoven and Brahms.

And at a time when much of the academy has lost interest in history, contemporary classical-music culture is one of the last redoubts of the humanist impulse. The desire to know the past has grown white-hot among certain musicians over the last 50 years, resulting in a performance revolution that is the most dynamic musical development in recent times.

A twenty-first-century music lover plunged into the concert world of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries would find himself in an alien land, surrounded by strange customs and parochial tastes. Works that we now regard as formally perfect were dismembered: only a single movement of a work’s full three or four might ever be performed, with the remaining movements regarded as inessential. Musical forms, such as the sonata, that are central to contemporary performance practice were kept out of the concert hall, considered too difficult for the public to absorb. And the universal loathing directed by today’s audiences at the hapless recipient of a mid-performance cell-phone call would have struck eighteenth-century audiences as provincial, given the widespread use of concerts and opera as pleasant backdrops for lively conversation.

But the greatest difference between the musical past and present is what we might call musical teleology: the belief that music progresses over time. That belief had consequences that many contemporary listeners and musicians would find shocking. Throughout much of Western history, older works held little interest for average listeners – they wanted the most up-to-date styles in singing and harmony. Seventeenth-century Venetians shunned last year’s operas; nineteenth-century Parisians yawned at the elegant entertainments written for the Sun King. Composers like Bach, today viewed as cornerstones of Western civilization, were seen as impossibly old-fashioned several decades after their deaths. In his 1823 Life of Rossini, Stendhal wondered: “What will happen in twenty years’ time when The Barber of Seville [composed in 1816] will be as old-fashioned as Il Matrimonio Segreto [a 1792 opera by Domenico Cimarosa] or Don Giovanni [1787]?” Stendhal’s musical crystal ball obviously had its flaws.

Berlioz was in many ways a musical teleologist himself, but he fiercely opposed the widespread outcome of the belief in musical progress: the posthumous rewriting of scores. Performers and publishers unapologetically revised works that we now regard as transcendent, seeking to correct their perceived deficiencies and bring them up to newer standards of orchestration and harmony. After describing a particularly brutal mauling of The Magic Flute for its 1801 Paris premiere and a dumbing-down of Carl Maria von Weber’s Der Freischütz, Berlioz erupts: “Thus, dressed as apes, got up grotesquely in cheap finery, one eye gouged out, an arm withered, a leg broken, two men of genius were introduced to the French public! …No, no, no, a million times no! You musicians, you poets, prose-writers, actors, pianists, conductors, whether of third or second or even first rank, you do not have the right to meddle with a Shakespeare or a Beethoven, in order to bestow on them the blessings of your knowledge and taste.”

Conservative pedagogues altered scores as well – on the ground that they were too modern. Berlioz headed off at the last minute what he called “emasculations” to Beethoven’s avant-garde harmonies that the influential music critic and teacher François-Joseph Fétis had surreptitiously introduced into a forthcoming edition of Beethoven’s symphonies.

For all Berlioz’s efforts to preserve the score’s integrity, however – during a performance of Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride, he shouted from the audience: “There are no cymbals there. Who has dared to correct Gluck?” – he could not dislodge the practice of “improving” older works of music. Virtuosi added to a piece whatever fireworks the composer had carelessly neglected to include. In 1837, Franz Liszt had a pang of conscience over his habit of pumping up his performances of Beethoven, Weber, and Johann Nepomuk Hummel with rapid runs and cadenzas. He briefly saw the error of his ways: “I no longer divorce a composition from the era in which it was written, and any claim to embellish or modernize the works of earlier periods seems just as absurd for a musician to make as it would be for an architect, for example, to place a Corinthian capital on the columns of an Egyptian temple.” But he soon fell off the wagon and went back to crowd-wowing revisions, reports Kenneth Hamilton in his mesmerizing study of Romantic pianism, After the Golden Age.

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the concept of a musical canon emerged and displaced the zeal for new music in concert programming. Yet the updating of scores continued. Gustav Mahler added new parts for horns, trombones, and other instruments when he conducted Beethoven’s symphonies. An influential edition of Beethoven’s piano sonatas by the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow recommended that pianists substitute Liszt’s ending of theHammerklavier Sonata for Beethoven’s own, “to give the closing measures the requisite brilliancy.”

Even in the canon-revering twentieth century, the teleologists remained cheeky. Arnold Schoenberg explained his reorchestration of Handel’s Concerti Grossi, op. 6, as remedying an “insufficiency with respect to thematic invention and development [that] could satisfy no sincere contemporary of ours.” At the start of a 1927 recording of Chopin’s Black Key Étude, the pianist Vladimir de Pachmann announces: “The left hand of this étude is entirely altered from Chopin: it’s better, modernized, more melodic, you know.” A contemporary listener, drawn to Beethoven, Handel, and Chopin precisely for what is unique in their voice and sensibility, can only marvel at the confidence with which earlier generations declared such music in need of improvement.

In the second half of the twentieth century, a performance practice broke out that rejected, in the strongest possible way, the teleological understanding of music. An overwhelming drive possessed certain conductors, instrumentalists, and singers to re-create the music of the pre-Classical era – from the medieval through the baroque periods – as it was performed at the time of its composition.

These musicians discarded the modern steel-strung and -armatured instruments that had evolved in the nineteenth century and learned to play the gut-strung, fragile instruments of the Renaissance and baroque periods. They pored over music treatises, prints, and other historical materials to discover, say, how a seventeenth-century violinist attacked his instrument, how he handled the shorter, curved bow of the period, how he phrased and ornamented a line, how much vibrato he used. Needless to say, any thought of “modernizing” a score’s harmonies or orchestration was out of the question. These history-obsessed musicians didn’t want to bring the music of the past into the present; they wanted to enter the past on its own terms. The stylistic particularities of older music that, according to the teleologists, limited its potential, were for these revolutionaries its very essence.

The results were a revelation. The sound of these performances of Bach, Handel, and Vivaldi was light and nuanced; the music pulsed with energy. Trading the large modern orchestra for small baroque ensembles of temperamental instruments was like exchanging a leather-upholstered Cadillac for a frisky, unbroken colt. The premodern horns – unreliable and highly prone to indiscretions – blared out with a glorious astringency. The timpani shot from the orchestra with hair-raising force. Conductors emphasized the dance elements in baroque music, inflecting certain beats within measures as a courtier might beckon to his dance partner. An unfamiliar and seductive voice – the countertenor – emerged to take on roles in baroque operas and masses that castrati originally sang.

This “early-music” movement (also known as “period-instrument” and “authentic-performance”) was a deliberate strike against the classical-music establishment. It provoked a counterreaction and a sharp philosophical debate about the nature of performance and the proper role of historical knowledge in music-making (see appendix). Listeners and performers remain divided over whether the music of Bach and Mozart is best realized by a nineteenth-century-era orchestra using contemporary methods of expression (violinist Itzhak Perlman maintains: “I’m certain Haydn and Mozart would have adored our modern approach to phrasing and vibrato”) or by a small period-instrument ensemble seeking to re-create earlier performance techniques.

But regardless of such disagreements, the value of the movement to our musical life has been indisputable. It has unleashed arguably the most concentrated rediscovery of lost music in history. Composers that had lain silent for centuries – Jean-Féry Rebel, Johann Friedrich Fasch, Heinrich Ignaz Biber, to name just a handful – are heard again. Hundreds of groups of specialists are busily digging into twelfth-century plainchant and thirteenth-century troubadour traditions. Unfamiliar repertoire by overly familiar composers is also being restored. The Naïve label, in one of the greatest recording projects of the early-music movement, is releasing all of Vivaldi’s operas. A wind blows through these magnificent, mostly unpublished works, but even when the rhythms are most propulsive, a deep melancholy pervades the music. Naïve’s recording of the haunting duet for mezzo and chalumeau (a proto-clarinet) from the oratorio Juditha Triumphans, “Veni, me sequere fida,” is alone a contribution to civilization.

The public’s ear for this music has expanded accordingly. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a few aristocratic salons hosted private performances of Renaissance and early baroque music, but outside those elite settings, there was no commercial demand for pre-Classical music. Today, by contrast, enough people are eager for works from remote eras to put the medieval a cappella ensemble Anonymous 4 on the top of Billboard charts. Jordi Savall’s Renaissance music group Hesperion XXI brings audience members to their feet during performances. Early-music festivals have even reached Missoula, Montana, where Heinrich Schütz’s Musikalisches Exequien was performed in March 2010, and Indianapolis, which offered Spanish ballads from the time of Cervantes in June 2010. The New York vocal group Polyhymnia invites its audience to “glimpse behind the tapestried walls of the ducal court at Munich, to hear the psalms kept for the private use of their patron,” assuming in their listeners the same desire to know the past that animates the performers themselves. Amateurs also perform this previously discarded music. Camps teaching medieval chant are ubiquitous, from Evansville, Indiana, to Litchfield, Connecticut. Reed, viol, and lute players can brush up on their skills at the Summer Texas Toot in Austin; San Jose, California, hosts a workshop for recorder players.

The movement has also demolished one tiresome credo of classical-music critics: that the way to revitalize the concert tradition is to program contemporary music. It is surely the case that the concert repertoire, derived from a narrow slice of the musical universe, is in desperate need of new music. But the critics are wrong in defining “new music” exclusively as contemporary. The public could not be more unequivocal: it finds little emotional significance in most contemporary classical music, especially that produced in academic enclaves. The early-music movement offers two alternative definitions of “new music”: the standard repertoire, such as Mozart’s symphonies, performed in entirely new ways; and unknown repertoire from the pre-Classical period. Though the reinterpretation of the standard repertoire has had the biggest commercial impact, it is the second definition of “new music” that should animate concert programming today. Countless compelling works, not just from the pre-Classical period, cry out for rediscovery: Haydn’s Sturm und Drang symphonies, Dvořák’s piano music, and virtually unknown composers such as Zdeněk Fibich. Thousands of listeners, frustrated by the constricted concert canon, would eagerly support the performance of unknown old music.

The caliber of musicianship also marks our age as a golden one for classical music. “When I was young, you knew when you heard one of the top five American orchestras,” says Arnold Steinhardt, the first violinist of the recently disbanded Guarneri Quartet. “Now, you can’t tell. Every orchestra is filled with fantastic players.” Steinhardt is ruthless toward his students when they’re preparing for an orchestra audition. “I’ll tell them in advance: ‘You didn’t get the job. There are 250 violinists competing for that place. You have to play perfectly, and you sure didn’t play perfectly for me.’ ”

The declinists who proclaim the death of classical music might have a case if musical standards were falling. But in fact, “the professional standards are higher everywhere in the world compared to 20 or 40 years ago,” says James Conlon, conductor of the Los Angeles Opera. A vast oversupply of students competing to make a career in music drives this increase in standards.

Much of that student oversupply comes from Asia. “The technical proficiency of the pianists from Asia is staggering,” says David Goldman, a board member at New York’s Mannes College of Music, where applications are at a record high. “They arrive here with these Popeye arms, and never miss a note.” Asia has fallen in love with classical music; many parents believe that music training is an essential part of their children’s development. “The only way to survive when you’re in a pool of literally hundreds of thousands of other Asian kids is to outwork your competition,” says Tom Vignieri, the music producer of the effervescent NPR show From the Top, which showcases school-age classical musicians.

Far Eastern countries are trying to build up their own conservatory system to meet the demand for music training – Robert Dodson, head of the Boston University School of Music, recalls with awe the Singapore Conservatory’s 200,000 square feet of marble – but so far, demand outstrips supply. When Lang Lang, today an internationally acclaimed pianist, was admitted to Beijing’s Central Conservatory in the early 1990s, he was one of 3,000 students who had applied for just 12 fifth-grade spots. And those 3,000 were the cream of the 50 million children who study music in China, including 36 million young pianists.

For now, the West’s conservatories continue to attract Asia’s top talent. Nineteen-year-old Meng-Sheng Shen, a slender freshman at Juilliard, dreamed of a concert career while still a piano student in Taiwan. “In Taiwan, I felt: ‘It’s not that hard to win,’ ” he says. In New York, however, “you see a lot of people who play really well,” Shen marvels, and so this acolyte of Chopin, Liszt, and Rachmaninoff has recalibrated his plans to include the option of teaching as well as concertizing.

Plenty of young Americans, too, are pursuing training in the nation’s 600-plus college music programs, whose unlikely locations, such as at California State University, Fresno, testify to the far-flung desire for musical sublimity. An efficient talent-spotting machine vacuums up promising young oboists and violinists from every Arkansas holler and Oregon farm town and propels them to ever-higher levels of instruction and competition.

The poise and exuberance of these budding performers can be breathtaking. At the 2007 finals for the Metropolitan Opera’s National Council Auditions, a young tenor’s eyes shone with the erotic power of commanding that massive house, a smile of mastery playing over his lips, as he flung out the high Cs of “Ah! mes amis” from Donizetti’s La Fille du Regiment. (The moment was captured in the documentary The Audition.) A self-possessed black pianist from Chicago, Jeremy Jordan, coolly unfurled the feathery arpeggios and midnight harmonies of his own virtuosic transcriptions of Wagner, Richard Strauss, and Saint-Saëns at a Juilliard student recital this year. Beneath Jordan’s laconic demeanor lies a deep belief in classical music. “It’s not as if kids don’t like music like this,” the lanky 20-year-old insists. “Liszt, Wagner, Chopin – it’s beautiful; it just takes one hearing.”

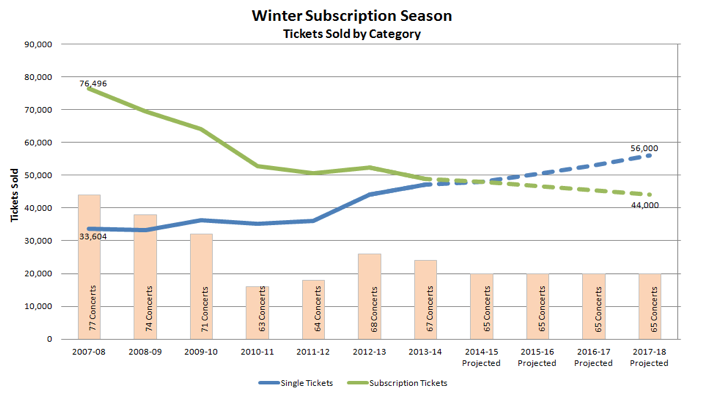

But however vibrant classical music’s supply side, many professionals worry that audience demand is growing ever more anemic. Conlon calls this imbalance the “American paradox”: “The growth in the quantity and quality of musicians over the last 50 years is phenomenal. America has more great orchestras than any country in the world. And yet I don’t know of a single orchestra, opera company, or chamber group that isn’t fighting to keep its audience.” The number of Americans over the age of eight who attended a classical-music performance dropped 29 percent from 1982 to 2008, according to the League of American Orchestras (though attendance at all leisure activities plummeted during that period as well, including a 36 percent drop in attendance at sporting events).

Recent conservatory graduates, struggling for work, find their commitment to a music career tested almost daily. “The culture seems to have a shrinking capacity for what I love,” says Jennifer Jackson, a 30-year-old pianist who studied at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore. The audience has a limited ability to follow serious music, Jackson says. “To make a profit, you have to intersperse lots of things that people can handle musically.”

These perceptions, however valid, should be kept in historical perspective. Much of today’s standard repertoire was never intended for a mass audience – not even an 1820s Viennese “mass audience,” much less a 2010 American one. Nineteenth-century performers regarded the music that constitutes the foundation of today’s repertoire with trepidation, since they feared – rightly at the time – that it would prove too challenging for the public. Composers wrote sonatas and chamber works either for students or for private performance in aristocratic salons, not for public consumption. True public concerts – those intended to make a profit – resembled The Ed Sullivan Show, not the reverential communing with greatness that we take for granted today. Light crowd-pleasers – above all, variations on popular opera themes – leavened more serious works, which were unlikely to be performed in their entirety or without a diverting interruption. At the 1806 premiere of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in Vienna, the violinist played one of his own compositions between the concerto’s first and second movements – on one string while holding his violin upside down. Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony premiered at Paris’s leading concert venue in 1832 with romances and tunes by Weber and Rossini spliced between the third movement and the choral finale, according to James Johnson in Listening in Paris.

By the end of the nineteenth century, public concert practice more closely resembled the norm today, with symphonies and sonatas usually performed in their entirety and without other works spliced into them. Many soloists began performing marathon recitals of highly demanding works. This programming of exclusively serious music for public consumption in the late nineteenth century was no more consistent with how that music was originally performed than it is now, and it represented as much of an unforeseen advance in the listening capacities of the public.

Today’s classical-music culture differs from the past in one more important way: recording technology. No composer before the advent of the gramophone ever anticipated that his music would be endlessly and effortlessly repeatable. At best, he might hope that his musician friends would give a few additional performances of his latest piece before new styles and works superseded it. The ease of repetition that recording technology enabled puts an enormous strain on the excessively limited canon that emerged from the nineteenth century – one that could have proved fatal. Yet not only have Schubert’s piano sonatas and Chopin’s nocturnes, Beethoven’s string quartets and Brahms’s intermezzi, survived the move from the private salon to the public concert hall; they have triumphed over the potentially stupefying overfamiliarity inflicted on them by instant replay and the accumulating weight of hundreds of thousands of performances. The exquisiteness of this music is such that it continues to seduce, decades and centuries after its expected eclipse.

The radical transformation of how people consume classical music puts the current hand-wringing over an inattentive, shrinking audience in a different perspective. Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony premiered before an audience of 100 at most. These days, probably 10,000 people are listening to it during any given 24-hour period, either live or on record, estimates critic Harvey Sachs. Recordings have expanded the availability of music in astounding ways. The declinists – led by the industry’s most reliable Cassandra, the League of American Orchestras – do not account for how recordings have changed the concert culture beyond recognition.

Recordings have also, it is true, taken a toll on the communal, participatory aspect of music-making. But the explosion of classical music on the Internet has revived some of that communal element. The ever-expanding offerings of performances on YouTube, uploaded simply out of love, demonstrate the passion that unites classical-music listeners. A listener can compare 15 different interpretations of “Là ci darem la mano” at the click of a mouse, all – amazingly – for free. Organized websites, such as the live classical-concert site InstantEncore.com, are creating new ways of disseminating music that will undoubtedly reach new audiences. Even with recording technology’s impetus for passive, private listening, the percentage of amateur musicians studying classical music has risen 30 percent over the last six years, from an admittedly small 1.8 percent to 3 percent. Many of those nonprofessional musicians, as well as their children, are uploading their own performances onto the Web.

Contrary to the standard dirge, the classical recording industry is still shooting out more music than anyone can possibly take in over a lifetime. Has the pace of Beethoven symphony cycles slowed down? We’ll survive. In the course of one month arrive arias by Nicola Porpora, an opera by Federico Ricci, a symphony by Ildebrando Pizzetti – three composers previously known only to musicologists – Cherubini’s Chant sur la Mort de Joseph Haydn, and Haydn’s The Storm. This cornucopia of previously lost works is more than any of us has a right to hope for.

The much-publicized financial difficulties of many orchestras during the current recession also need to be put into historical perspective. More people are making a living playing an instrument than ever before, and doing so as respected and well-paid professionals, not lowly drones. There were no professional orchestras during Beethoven’s time; he had to cobble together an ensemble for the premiere of his Ninth Symphony. Even mid-twentieth-century America had no year-round, salaried orchestras. In 1962, most concert seasons were half a year long.

But under pressure from an increasingly militant musicians’ union and with an infusion of funding from the Ford Foundation in 1966, many orchestras started paying their players annual, or close to annual, salaries. In part to justify those higher salaries, orchestras expanded their concert seasons and the frequency of concerts within each season. Neither Beethoven nor Brahms envisioned that a single orchestra would perform three or four concerts a week, critic Joseph Horowitz notes in Classical Music in America, much less that its members would draw six-figure salaries. The low pay of a typical late-nineteenth-century musician made possible the huge orchestral forces that Bruckner and Mahler summoned as a matter of course. Today’s composers usually write for much smaller ensembles, having been priced out of the symphonic form by unionized wages.

Nevertheless, professional orchestras in the US today dwarf in number anything seen in the past. In 1937, there were 96 American orchestras; in 2010, there are more than 350. Where union restrictions don’t exist, the music scene is even more vibrant. Volunteer adult orchestras outnumber professional orchestras two to one. New youth ensembles launch every year; there are now nearly 500 in the United States. Though Los Angeles County alone has more than 40 youth orchestras, the leading state in student involvement is Texas, where more than 57,000 high school musicians auditioned last year for slots in prestigious all-state music ensembles.

Chamber-music groups have also proliferated in the last 50 years. Arnold Steinhardt recalls that back when he was studying the violin, you could count on one hand the number of string quartets and other ensembles: “Chamber music was not a profession then; it was for people who weren’t good enough to have a solo career.” Nowadays, new quartets form constantly, many associated with colleges and universities. It took nearly the entire nineteenth century for the string-quartet repertoire to broaden its appeal beyond a narrow band of connoisseurs; today, the audience for chamber music extends far beyond traditional urban centers of culture. Iowa City hosted a Haydn quartet “slam” last year in honor of the 200th anniversary of the composer’s death. String players from ages eight to 78 performed all 83 of Haydn’s quartets.

It is fair to ask whether the foundation-fueled postwar expansion of orchestras artificially and unsustainably pumped up the supply of musicians and ensembles. But there is ample evidence of a continuing unmet demand for classical music throughout the country – especially in places that can’t afford the salaries and long seasons that America’s unionized musicians expect. This March, the New York Times’s invaluable Daniel Wakin chronicled the travails of the Moscow State Radio Symphony Orchestra as it slogged through a poorly paid nine-week bus tour to smaller cities and towns around America – places like Ashland, Kentucky, and Zanesville, Ohio, which are “hungry for classical music programming.”

It’s even harder to spot a demand deficit at the other end of the glamour spectrum. Though Wagner fans incessantly lament the shortage of Heldentenors, the source of the problem is not a decrease in capable Siegfrieds and Tristans but the mushrooming of Ring cycles in China, Russia, and Japan, among other locales. Likewise, as Plácido Domingo explains in a collection of interviews called Living Opera, hand-wringing about singers who find themselves pushed too early into roles for which they are not yet ready reflects the worldwide increase in theaters and opera companies, which require a constant supply of singers.

However bounteous today’s classical-music culture is for those already inside it, the number of children who have the opportunity to be captivated by classical music is still much lower than it ought to be. “The arts fell out of US schools in the 1980s; all the music is gone,” James Conlon observes in Living Opera. “Now we have a generation of adults who make money, accomplish what they think is the fulfillment of life, but they’ve never had any contact with the classical arts – neither music nor literature. For me that’s a national disgrace.” Most leading music institutions have energetic outreach programs to try to compensate for the loss of public music education. But some school bureaucracies make no effort to accommodate these programs.

The public schools’ sclerosis has fueled the growth of community music schools that offer low-cost private lessons and ensemble work to children and their parents. The schools, heirs to the music program for immigrants at Chicago’s Hull House, are particularly important in urban areas, where arts education has withered far more than in suburban and rural school districts. Philadelphia’s buoyant network of schools trains thousands of students each year.

Such endeavors could reach far more children if they enjoyed better funding. That will require changing the priorities of America’s patron class, says Leon Botstein, the president of Bard College and conductor of the American Symphony Orchestra. “What is different today is that the nation’s elite, the very rich, don’t care about classical music,” he observes. “The patron class is philistine; instead of Andrew Carnegie, we have Donald Trump. Some rich guy with a hedge fund wants to be photographed with Angelina Jolie, not support the Cleveland Orchestra.” Bill Gates didn’t help matters when he proclaimed gratuitously: “I have no interest in giving to opera houses.” Younger philanthropists seem to be following Gates’s lead in spurning the arts, write Matthew Bishop and Michael Green in Philanthrocapitalism. The celebrity-bedecked Robin Hood Foundation enjoys extraordinary cachet on Wall Street; organizations that promote classical culture, far less so.

Two of the best hopes for building future American audiences may come from outside the country. Gustavo Dudamel, the 29-year-old Venezuelan conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, is the closest thing the classical-music world has to a Leonardo DiCaprio. His tousle-headed exuberance, thousand-watt smile, and undoubted conducting skills have thrilled the press and public and created huge interest in his future career.

But it is Dudamel’s past that may be his most important contribution to classical music. Dudamel is the most famous graduate of Venezuela’s initiative to teach slum children to play classical instruments, and in so doing to develop the self-discipline that will carry them out of the ghetto. More than a quarter-million poor children in Venezuela enroll in the nearly 200 youth orchestras that belong to El Sistema Nacional de las Orquestas Juveniles e Infantiles de Venezuela (“El Sistema,” for short). In 2002, another El Sistema graduate, the double bassist Edicson Ruiz, became at 17 the youngest musician ever to join the Berlin Philharmonic. The brainchild of José Antonio Abreu, a left-wing economist committed to “social justice,” El Sistema could not be a stronger rebuke to the multicultural dogma that currently governs American education and welfare programs. Its premise is that all children should be exposed to the West’s highest artistic accomplishments. “The huge spiritual world that music produces in itself ends up overcoming material poverty,” Abreu has said. “From the minute a child is taught how to play an instrument, he’s no longer poor.”

Dudamel’s charisma and hip Latino ethos could make it safe for Silicon Valley moguls to fund classical-music education without worrying about accusations of elitism. Perhaps the sight of Venezuela’s Simón Bolivar Youth Orchestra playing its heart out could persuade even the liberal Ford Foundation to return to its roots in classical arts funding. “We have lived our whole lives inside these pieces,” Dudamel says. “When we play Beethoven’s Fifth, it is the most important thing happening in the world.”

Thanks to the publicity around L.A.’s new conductor, an initiative headquartered at the New England Conservatory of Music now trains music postgraduates to start local El Sistema programs worldwide. But much more could be done. Why not a Play for America program, modeled on Teach for America, that would send music graduates into poor communities to teach and perform for two or three years?

The other source of future classical-music demand is China. “I’m very hopeful,” says Robert Sirota, head of the Manhattan School of Music. “If China graduates 100,000 pianists a year, it changes everything.” The best predictor of attendance at classical concerts is playing an instrument. Asia’s passionate pursuit of music training for its children will create not just tomorrow’s professional musicians, of whom there is no dearth, but tomorrow’s audiences as well. And like El Sistema, the phenomenon of countless poor young Asians practicing fanatically for the privilege of a career performing Scarlatti and Rachmaninoff torpedoes the image of classical music as the bastion of wealthy white elites. When the 12-year-old Lang Lang competed for the first time with Europeans, he worried that their heritage would give them an interpretive advantage. “It’s your native music as well,” his father reminded him. “It belongs to anyone who loves it.”

Music records the evolution of the human soul. To hear how the elegance of the baroque developed into the grandeur of the classical style, which in turn gave way to the languid sensuality and unbridled passion of Romanticism, is to trace how variously human beings have expressed longing, desire, triumph, and sorrow over the centuries.

Not everyone will hear that changing sensibility; some may find the soul’s echo elsewhere. But the present-day abundance of classical music – of newly rediscovered works, consummate performances, thousands of recordings, and legions of fans – is a testament to its deep roots in human feeling. And it is a cause for celebration that so many people still feel drawn into its web of lethal beauty, in a world so far from the one that gave it birth.

Appendix: The Early-Music Quarrel

By the mid-twentieth century, nearly all performers respected the letter of the score and dedicated themselves to realizing its spirit as well. But to the early-music advocates, the establishment musicians seriously misunderstood that spirit, at least regarding the pre-Classical repertoire.

Over the course of the twentieth century, the baroque composers – above all, Bach and Handel – had been taking on more and more weight and waddling ever more ponderously, as mainstream conductors assimilated them to late-Romantic performance styles. Early-eighteenth-century works sounded suspiciously Wagnerian – with long legato lines and a smooth, creamy sound, performed by ensembles many magnitudes larger than anything ever marshaled during the baroque or classical eras. Conductor Ivan Fischer recently recalled a Leopold Stokowski performance of Bach, after which musicians left the stage to pare down for Bruckner, the epitome of late-Romantic gigantism. While massive ensembles may have magnified the spiritual force of the music for some listeners, the orchestral inflation at the very least obscured the intricate contrapuntal writing for different instrumental voices. With a chorus of 200, no one is going to hear the flutes delicately doubling the sopranos’ line in a Bach oratorio.

In rejecting this supersized sound, the early-music acolytes (whose first modern wave included Gustav Leonhardt, Frans Brüggen, Nikolas Harnoncourt, Ton Koopman, and Christopher Hogwood) embraced a fallen historical consciousness, compared with the prelapsarian innocence of mainstream musicians. (The authenticity movement had late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century antecedents, but those early experiments never achieved critical mass.) Where the great titans of traditional twentieth-century performance – conductors such as Wilhelm Fürtwangler and Otto Klemperer – assumed a continuity between the past and the present that guaranteed the fidelity of their interpretations, the early-music advocates saw discontinuity. The essence of the music of the past was no longer intuitively available to us but required historical research to recover, they believed. A gulf separated Bach’s world from ours; we could no longer assume that modern performing traditions expressed his intentions.

The early-music movement quickly attained commercial success and just as quickly provoked a backlash, primarily from musicians who objected to the implication that their performances were inauthentic. Some objections were aesthetic: these old instruments sound weak and thin, critics said; stronger models have superseded them for good reason. We need a revival of period strings as much as we need a revival of period dentistry, one wag observed. In a 1990 interview, violinist Pinchas Zuckerman called historical performance “asinine STUFF… a complete and absolute farce. Nobody wants to hear that stuff.”

Other objections were normative. “Musical archaism may be a symptom of a disintegrating civilization,” musicologist Donald Grout wrote at the start of the modern period-instrument movement. A composer of early music, if he came back to life today, would be astonished by our interest in how music was performed in his own times, Grout asserted. “Have we no living tradition of music, that we must be seeking to revive a dead one?” the composer would ask.

The most interesting challenges to the historical-performance movement, however, have been philosophical. Historically accurate performance is unattainable, critics like Richard Taruskin of the University of California at Berkeley charged. There are too many stylistic unknowns, too many variables regarding tempo and phrasing, to think that treatises on technique or illustrations of musicians playing an instrument can lead to the movement’s Holy Grail: the way a piece sounded at its creation. Further, the very idea of an authentic performance is incoherent, the skeptics said: Which performance of a work should we view as authentic? Its premiere? But what if that performance – or every subsequent one during a composer’s lifetime – failed to realize the composer’s conception because of inadequate rehearsals or mediocre musicians, as Berlioz so frequently experienced?

The naysayers pointed out that the context of musical performance has changed so radically from the pre-Romantic era that we cannot hope to re-create its original meaning. For most of European history, music belonged to social ritual, whether it accompanied worship, paid homage to a king, or provided background for a feast. A large concert hall filled with silent listeners, focused intently on an ensemble of well-fed professionals still in possession of most of their teeth, has no counterpart in early-music history. Early-music proponents, the detractors added, are highly selective in their use of historical evidence. No one today conducts the operas of Jean-Baptiste Lully, for example, by pounding a staff on the floor, as conductors did in the court of Louis XIV to try to keep time in an ensemble of less-than-perfectly trained musicians.

Taruskin launched the intended coup de grâce. The predominant early-music style has nothing to do with historical evidence, he charged, and everything to do with the modernist aesthetic. The style’s fleet rhythms and transparent textures are a reaction against the excesses of subjectivity and expression characteristic of Romanticism; the shaky historical arguments on its behalf are just after-the-fact window dressing.

Several of the arguments against the period-instrument movement had bite. They reflect the skepticism regarding the possibility of knowing the past that dominates today’s universities and that gets used (improperly) to justify junking the study of history, philology, and literary tradition. The proponents of period performance heard and considered these sophisticated objections. Then something wonderful happened. They responded, in essence: “Yeah, whatever.” They tweaked their rhetoric, junked the term “authenticity” and anything else that sounded too authoritarian – and went right on doing what they had been doing all along. That is because their hunger for the past – for discovering how the musicians at the Esterházy palace interpreted crescendi or how much vibrato a cellist performing Bach’s cello suites in the 1720s would have used – was so great that no amount of hermeneutical skepticism could extinguish it.

The influential restorer of French baroque opera, conductor William Christie, exemplifying this attitude, lamented in 1997 how little we know about the hand gestures used in ballets and operas in pre-Revolutionary France. Gestural art is “a field that is painful for me right now,” he told Bernard Sherman in Inside Early Music. Christie’s pain is precious. It comes from an instinct in short supply in the rest of the culture: the belief that the past contains lost worlds of expression that would enrich us if we could just recover them. The desire to learn how a shepherdess in a Rameau opera may have inclined her hand to Cupid is an attribute of an enlightened humanity. (Unfortunately, Christie has since abandoned the project of re-creating baroque opera stagings and choreography, leaving the Boston Early Music Festival and Opera Lafayette as the sole ensembles committed to courtly theatrical sensibility as well as musical practice.)

An early informal truce between modern-instrument ensembles and the historicists has long since broken down. According to this unwritten understanding, the historicists would claim the pre-1800 repertoire, while leaving nineteenth-century works to the modern symphony orchestra. It was not long, however, before the proponents of historical “authenticity” marched all the way into the twentieth century, blithely piling one historical anachronism onto another, as if to confirm Taruskin’s skepticism regarding the evidentiary basis for their work. Period-instrument groups such as the Philharmonia Baroque and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique use the evocative Waldhorn in Brahms’s works, for example, even though Brahms himself could not persuade his contemporary brass players to give up their spiffy new valved horn for that difficult ancient instrument. In addition to adopting “historical” practices that didn’t exist, the historicists ignore widespread nineteenth-century performance traditions that did exist. There has been no movement to revive “preluding,” for example, in which a pianist improvised chords and arpeggios before breaking into the actual published score of a work, because such behavior would too forcefully violate contemporary concert norms. Nor has the habit of teleologically updating scores been adopted. This paradox points to the conceptual meltdown point of the authenticity movement, where it becomes clear that the most unhistorical practice in the history of music is the concern for authenticity.

Such conundrums do not subtract from the enormous contribution that the early-music movement has made to our experience of music. Traditional orchestras, especially in Europe, have subtly changed their sound and approach to the standard repertoire in response to the competition. Sadly, we will never know whether the period-instrument movement has come close to past performance style (though Taruskin is wrong that historical materials cannot provide meaningful guidance). But the effort to recover our musical past remains a noble one.