EDITOR’S NOTE: This is an edited transcription of the lecture delivered by Léon Krier at our inaugural The Future of the Symphony Conference in September 2014. The video of this lecture can be viewed here.

Many of our doings and sayings are really motivated by fear. René Girard, who is well known in this country, has differentiated very clearly desires – metaphysical desires, desires which are directly motivated by bodies, and desires which imitate other desires but which are not felt, which are not considered to be of strict necessity. We still do not quite understand what motivates this desire – that the desire of desire can be stronger than the desire itself. For instance, Girard identifies anorexia as not a physical but a mental debility in which somebody desires something that he does not understand and that can destroy him. And fashion is really that phenomenon which explains or realizes the extraordinary dominance nowadays of metaphysical desire. How otherwise to explain the fact that, for about eighty years now, many gifted musicians refuse to write music, but write a kind of anti-music which instead of giving pleasure gives pain?

How can one explain that despite the failure of modern architecture – which was very visible already from the start – such a flawed theory, demonstrated by extremely bad results in both the urban sense and the architectural/technological sense, came to be repeated so many times around the world and then became the dominant system, not only in our cities but above all in our education system, forbidding any reference to traditional architecture or urbanism except as something which is no longer allowed? I studied for two terms at Stuttgart University, and when I understood that what was being taught there was going to destroy any idea that had motivated me to study architecture, I gave up.

I had the extraordinary chance to have been born in a very beautiful environment, and I found the pleasure I had known in that formidable environment again this morning, very briefly at six o’clock, when I got up in my room here in the hotel. This is not a romantic vision of Caspar David Friedrich, but it’s actually the main square on Charles Street. It is this experience, this personal experience, that has marked anybody who is really interested in traditional architecture or traditional music. Most people are marked by this extraordinary experience, and I think the most important distinction which we have to make is that traditional architecture and traditional music are not historical phenomena, but transcendent phenomena. They are like language, or like mathematics, or like anything good: they are really atemporal goods – good beyond their time.

I try to educate my students to make a fundamental distinction – not to use the term historical architecture, but to distinguish traditional architecture and modernist architecture by a technological difference. In fact, traditional architecture is defined by technology, and therefore is atemporal. It is not linked just to the past, but is that experience of humans building at their scale because there is no other possibility. Obviously the use of fossil fuel energies has created the extraordinary possibility to ignore human capacities, to ignore climate, to ignore soil, and build virtually the same kind of buildings everywhere, independent of climate and of geography.

I grew up in Luxembourg City, which was virtually intact despite the Second World War that passed over and destroyed the northern part of the country. But I was educated in the small town of Echternach which had been completely destroyed by the Brunstad Offensif. Most of the American artillery was sitting on one side and they would bombard the Germans on the other by artillery, and on the way, they destroyed the city. This is considered by most people as an historic city but is in fact a reinvention of the 1940s and 1950s. I grew up in these building sites and it was an extraordinary experience which has lasted for a lifetime. I have pursued this kind of environment all my life. And I realize, now that I am 68, that all my theories and writings have been about how to make such an environment – not only to preserve it, but to create it ex novo.

I spend my summers in Mallorca practicing music, and also under this porch I have been writing a book which is called Corbusier After Le Corbusier. In it I am reforming, correcting, and translating Corbusier’s ideas into traditional architecture. For a musician it would be extremely interesting (and I think there are people actually attempting) to take Pierrot Lunaire and write out the ideas – because there are ideas in Pierrot Lunaire as well as interesting forms and expressions – but to translate it in a mode of Mahler or of Mozart, or of anyone who wrote music which you can listen to the second time without getting bored.

Because what those great musicians have done is virtually invented a world from scratch, building on an enormous edifice of sounds, to create something which is entirely new, in the same way that architecture was invented two thousand, three thousand years ago – many, many centuries and millennia ago. Musical architecture, in that sense of symphonic monumentality and extraordinary spatial dimension, is something relatively new. It is such a glorious experience that you cannot imagine that it will go for a thousand years. There won’t be ten thousand Brahmses or Mozarts writing two thousand five hundred symphonies.

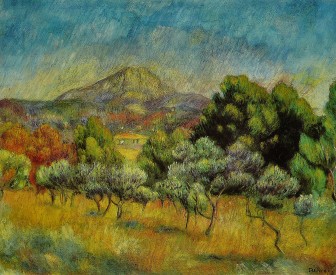

On the other hand, I think that, because they have discovered this world, once we have studied it and, with our sensibilities and the enormous talent which is born every day, met this world, that it will become our own. And then one can probably write a fifth or sixth Brahms symphony which will be as good as the first or second. I think it can be so because there really are new worlds. Discovering one is like moving into a painting – imagine a great landscape of Claude Lorrain and painting it the other way around. It’s virtually an invention of landscape but you can move in it. It’s actually what film does: from one image you create a world. The one world is concentrated in a single image.

I grew up as a modernist, of course, in revolt against my parents. My mother was a musician. I drove them mad with Schoenberg and Webern and so on. My mother always said of Stravinsky’s music, “What is this horse burial? Why do you play this?” And of course, my first building designs were extreme acts of provocation and protest. It’s really when I did my first project for the town where I had been educated, Echternach, that I realized Corbusier could no longer be my master – because plowing any of these enormous buildings which I had been drawing into such a town would mean utter destruction. It is only when I started doing these kinds of projects that I felt the necessity to really relearn a craft that is no longer taught.

Now, it took me twenty years to build the theory which is now being practiced as New Urbanism. It was truly an act of rediscovery – uncovering what had been done for thousands of years before. But what we do not do today is understand the motivating force of modernism. We really don’t understand what modernism is. Well, there are ways of approaching the problem or explaining it by metaphor and by allegory. Modernism in architecture – and music – is very much like the artificial invention of a language, like Esperanto. Esperanto was used by tradesmen and by a very small number of people. But imagine that a very powerful political group took over not just a province or a country, or even a continent, but over the world and imposed Esperanto as a single language, forbidding all other languages and declaring them as purely historical – no longer valid, no longer legitimate for use today. That is what has happened to architecture and even to music.

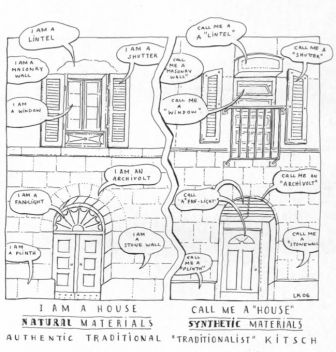

In architecture it can be explained very simply in a material way. Because of the introduction and use of fossil fuel energies and the fabrication of new building materials, like steel-reinforced concrete or plastics or plate glass – all of which we need enormous amounts of energies to produce – we can achieve building performances which before were not possible with traditional, natural materials. Yet there is no specificity to these new materials. Most people think that concrete or steel or the industrial production of nails created new architecture. In fact, it is not architecture that they created, because the forms which are possible with concrete are independent of the material and there is nothing you can’t cast – a classical arch in concrete as well as a square hole. There is nothing authentically modern to have square forms with concrete, or completely free forms. There is no form for these materials because they can be shaped in any way. You can cast the buildings, put them upside down, and they will be fine for a while. There’s no real authenticity with so-called modern materials.

And because there is very little experience, there is of course no language. There is no language comparable to the language of traditional architecture, which is extremely complex and which is very specific to regions or altitudes formed by different cultures and climates. I think if one used synthetic materials for a thousand years it is absolutely certain that human intelligence and senses and sensibilities will create a language to be the equivalent of traditional architecture, but it will take many centuries. We have not even started. That is why these buildings, which have been produced lately, are so completely out of control. They are just the size that some financial will or political will – or some kind of will independent of traditional scales – allows us to build. Now, when you consider that in the future fossil fuels will become extremely expensive, very scarce, and probably very difficult to use, suddenly we can see that the future of modernist architecture is very limited, and therefore also of modernist art.

The question is “What is modernism?” It is the excess of modernity. It is trying to be more modern than being modern. We are all modern – we cannot help being modern. Just by being here we are modern. So it is not a quality to be modern. We are modern whether we like it or not. It is a question of fate, not of choice. Whereas modernism is definitely something to do with an ideological scheme.

And this started much earlier than synthetic materials. It has to do with the development of Europe, with the political development and also the military expansion – this extraordinary will to expand beyond the limits of Europe and to absorb other cultures. Architectural language had been troubled for at least 250 or 300 years – well before modernism started. Modernism can actually be explained as a reaction against the trouble in the language.

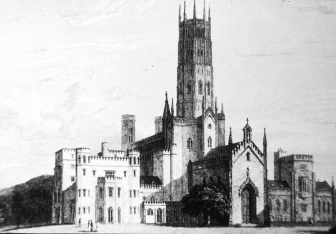

We began to see strange confusions. For instance, we find a building that looks like an abbey or a monastery – some religious building. In fact it is not an abbey. It is a house for a very rich man designed by a very talented architect. It pretends to be a monastery, but it is a house.

Or consider a building designed by the very talented architect Persius, who was a student of Schinkel; and though it looks like a mosque, it is not. It is a pumping station for the fountains of Pottsdam, built in the 1840s. This was the strange trouble in the language: why would one create buildings which would no longer represent what they historically mean?

You had then extremes like a simple block of flats in Geneva where you have the whole history and all the styles of the world you can imagine just unfolded for such a lowly purpose. And that leads to protest. It is so extreme and completely absurd, that there is no more language; there is just noise, messages that are meaningless, and it leads to protest and refusal.

Twenty years later, in 1914, a very talented architect in Denmark, Ivar Bentsen, foreshadowed the Bauhaus in two competitions for the opera in Copenhagen. The square was all the same architecture. You can only distinguish the opera house by a kind of tower which is dressed like it was an actual building. Modernism in that sense can be seen as a protest against Victorian excess, against this enormous outbreak of eclecticism.

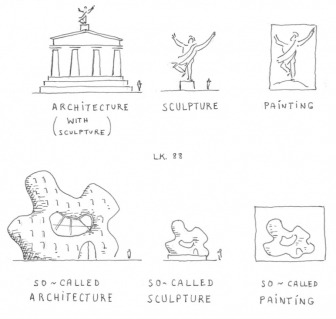

The protest led to other more important movements, producing buildings like the one Mies van der Rohe built it at the Illinois Institute of Technology. What is it? It is not a warehouse; it is a church. I think the cross has been replaced by a searchlight, which is very interesting.

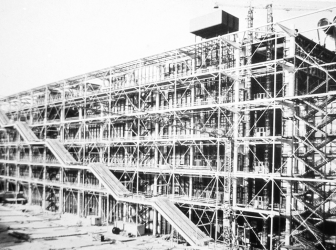

Then, of course, there is the Pompidou Center in Paris. Now the question is, if you build pumping houses which look like mosques, houses which look like monasteries, culture palaces which look like some oil refinery or some building having to do with industry, or a church which looks like a warehouse, what should monasteries look like? What should warehouses look like? What should industrial buildings look like, in order that there is no confusion? It’s very difficult to understand. These buildings, these reactions against Victorian excess, are considered to be more rational than Victoriana. In fact, they have very little to do with reason. The Pompidou Center was planned not only to have the walls move, but also the floors were meant to move up and down. That is why the structure was carried outside as were the stairs – so that everything could move because movement was meant to be progressive.

That is really where we are. How has progress – this idea of progress – come to dominate something which in fact should give stability? Historically, the stability of structure has never prohibited mobility of use. Throughout history we have buildings change use and change meanings; market buildings become churches and so on. There is a very long history of change of use, despite the solidity and immobility of the immobile. Immobilier in French and immobiliare in Italian refer to the fact that buildings are immobile. They do not move because they are not cranes or instruments. Now, why such a stupid ideology? That such an excessive set of ideas should become dominant is still difficult to explain.

At the same time the Beaubourg was built, Christian Langlois built an extension for the Senate building in Paris and Spreckelsen built his arch of La Défense. They are both modern architecture produced by the same regime. But of course the French state would never see itself symbolized by the building of Monsieur Langlois.

But whatever happened in the Beaubourg could be done in any kind of building. You didn’t need the mobility. Actually the mobility never happened: they built solid masonry walls inside, in order to have a proper museum. The floors never moved. You can perform that feat on oil derricks or boring platforms on the high seas because, though they are extremely expensive, they bring in inconceivable amounts of money. But, as we know, culture does not make direct income.

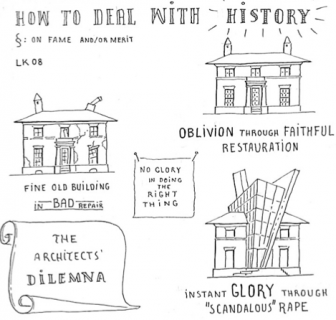

All this happened in architecture at an extremely large scale, destroying historic cities of incredible value. If a painter would take a painting of Gozzoli, a beautiful wall painting in San Gimignano, and would start to restore it in this manner – saying, “I don’t believe in historic restoration; I want to express myself, so we will restore Gozzoli!” – there would be world scandal. How can such an idiotic idea to destroy a really important work of art be funded? That is exactly what is happening not only to our cities but to our landscapes.

They are guided, and now disciplined and actually ordered, by two charters: the Charter of Athens and the Charter of Venice. And these cannot be reformed. I tried to understand this set of ideas – like the Charter of Venice, this completely absurd set of ideas – that says if you restore an historical building you must not imitate history. You have to differentiate anything you do by material, by color, by proportion, by character – in fact, you must violate the historic building. Otherwise it is not modern. That’s what the Charter of Venice says. The Charter of Athens stated long ago that cities should not be reconstructed as cities, but be divided, deconstructed in extremely large zones of single use – housing one way, culture another, education – all separate, and linked by public or private transport. They are unsustainable ideas, and yet they dominate the world.

And not only do they dominate the world, but they dominate particularly bureaucracy. And bureaucracy does not think. By its nature it cannot reflect critically on what it does. It must apply what it is told to do by law and by regulations which it is supposed to administer. And that is where the thing becomes extremely toxic, because when we now try to build traditional towns or traditional buildings we are faced with a bureaucracy that not only does not understand us but opposes us.

I became interested in an important project in the center of Moderna. The officer of restoration refused the project. We went to the minister in Rome and he sat down with us. He said, “Professor, can you tell us why you put peaked roofs on your buildings?” We were sitting in a room above Rome; we could see thousands of peaked roofs from where we sat.

I said, “I’m sorry. It is either peaked like this or inverted like that. You think there is a flat roof, but there is no flat roof. Have you ever looked at a flat roof? It is always leaning one way or the other because the water has to be carried away.”

“I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” he said, and we went on. But that is the mentality, because bureaucracy is not supposed to think.

A year later I had another project for the EUR district in Rome – a district built partially under Mussolini – and I was to restore the main square with a huge parking area going under the buildings. When the project was presented, everybody liked it. But the head of public monuments refused it, saying, “You cannot do imitative architecture. Mimetic architecture you cannot do.”

I responded, “But Signora, can you tell us what is non-mimetic architecture?”

“We are not supposed to engage in theoretical discourse.”

Again I said, “But Madame, we are imitative beings. Everything in nature is imitative, mimetic. Flowers imitate flowers, humans imitate humans, everything is imitative and repetitive.”

“We must not engage in theory,” and she stopped the project. It was never built. This is now the system which dominates our towns and cities, and it cannot be reformed. It will die its own death by the exhaustion of fossil fuels, or by simply becoming too expensive.

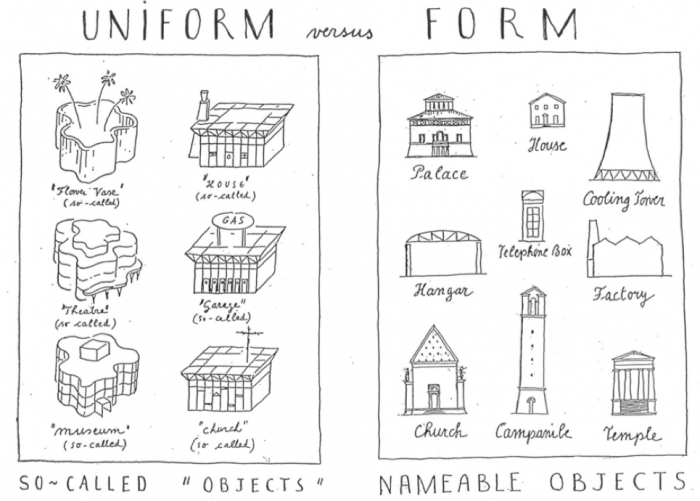

Traditional architecture is technology before any style. It is technology and typology of building solid buildings, responding to purposes of individuals or of communities, of small or large groups, and it is the accumulation of these experiences which creates the tradition. It is a technique to resolve the building in a pleasant, practical, and lasting way. Innovations happen when they are necessary. In the Middle Ages you do not invent hangars for airplanes. There are no airplanes. But when airplanes appear, there are suddenly hangars for airplanes. That is when innovation happens typologically. Most architects are educated nowadays to be inventive, to create typologies. They present a building and they say, “This is my typology.” Completely insane – a building is not a typology. No one can invent a typology just because he or she likes it. We are in a situation, really, of regression, not of advancement. The fear of backwardness, of not being “in tune”, not being “cool”, is I think paralleled by the fear of age. Why don’t people want to age anymore?

So they buy a beautiful, old house in a beautiful village and then they paint it red, flatten the roof, or make windows which don’t fit. It’s the idea of being different, but different from what? That is always the question. Because the fact is that we are all individuals. Whatever we do is individual. Whether we write, we sing, we walk, we stand, we cook, everything we do is marked by individuality. So there should not be any fear of not being individual. We cannot help being individual any more than we can help being modern. We are individual and we are modern. It is not something about which we should bother. Anyone playing the trumpet will play different from the one next to him, because the shape of his lips or his lungs is very different from that of the other, despite their being similar. This obsession with being individual, of developing individual expression, is nonsensical. And you can only develop individual expression within disciplines which are already shaped and which have been practiced.

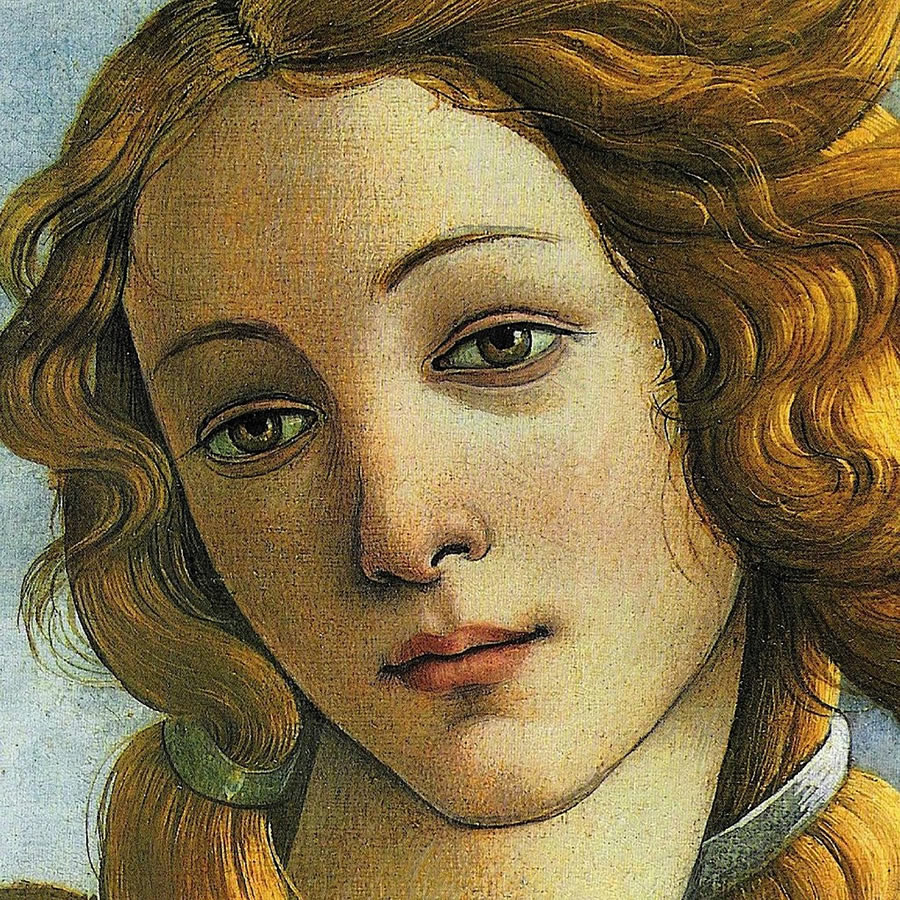

The thing now with modernist art that has dominated for so long is that we have no more art. Most museums of modern art for me could be closed down without any interest. My test is always this: if you take a piece of so-called modern art and you put it next to the dumpsters and rubbish in the courtyard and it is taken away, it’s not art – because anyone with any sensitivity or any intelligence will recognize a work of art. It has something more about it than just rubbish.

This is where I come to the parallel of music and architecture. Building a very large complex is symphonic work. If you build a large complex over twenty or thirty years – like building a town – you need some discipline which is going to ensure that there will be harmony of parts despite the contrarianism of the users who are going to inhabit it. You need some simple discipline, which can be understood and shared by a large number of people. That is what traditional architecture was about; and that is why we have these incredible treasures of traditional architecture still surviving, despite the will to deform or to destroy them or to wipe them out.

I am practicing this for the Prince of Wales in Poundbury, England and it has now several phases complete. We have built about 45 percent of it. It’s going better and better. It started with enormous difficulties, because the builders were not able to pursue such complex tasks. But now they have been trained and we have architects who have been well trained; and the buildings which come now after twenty years of work and practice are really extraordinary.

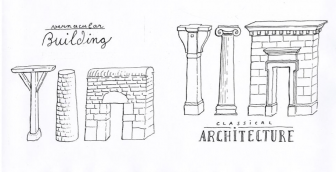

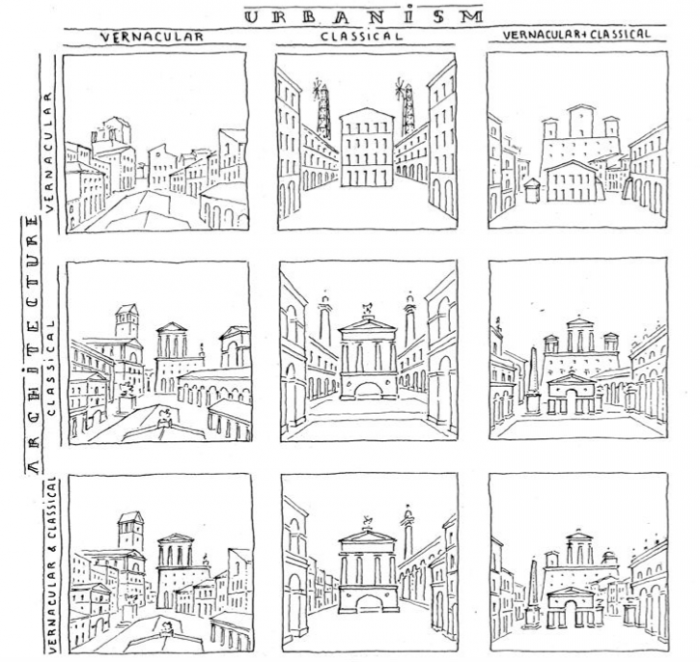

What is distinguishing about traditional architecture – and I think you will find a similarity in music and its universal differentiations – is the very great distinction between vernacular building and classical architecture. In all cultures which have practiced architecture in a systematic way, you have this distinction of vernacular building: very simple buildings which are just walls and pillars and roofs, representing a language of construction which does speak of nothing else but construction. A door is a door, a window is a window, a tile is a tile. There is no message beyond its own being, whereas classical architecture is something more. It is really an artistic translation of building beyond elements of construction into a language that transcends the pure utility of the simple nature of an opening or closure or embrasure or a covering. In Belgium for fifty years now we have given a prize which distinguishes between vernacular and classical architecture – because they are achievements which are of a very different nature, even though they are complementary. You can understand this clearly when you see it in a picture from Venice. Anyone can see which buildings are more important than the others because they are marked by a more elaborate language.

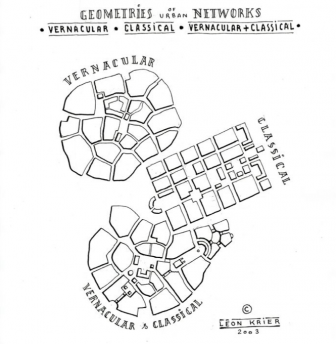

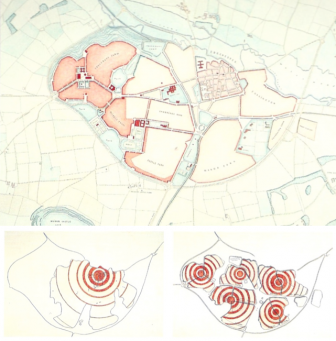

I introduce the differentiation of vernacular and classical in town planning because when people see a street that is not straight, not a gridiron design, they say, “Oh, it’s medieval.” It’s not medieval. Geometry in nature is always meandering. There is no straight line in nature. It’s an invention of the geometry of Euclid. There is no straight line and there is no square angle in nature. There is nothing regular or completely self-identical. It’s all similar, but still all slightly different. To have the correct terminology is very important if you reconstruct, because it’s not self-evident. It has to be so clear that people can easily accept it. Between the gridiron plan and more natural geometry there is enormous consequence for the experience and the use of towns.

The gridiron plan became the dominant technique of building towns in the Indies, in South and Central America, and also in North America where it was used almost exclusively – except in villages lost somewhere in the hills of West Virginia, let’s say. But once you conceptualize these two ideas, you can use them, because they are also intellectual models. You can use them to very powerful effect not only to espouse the land – vernacular geometry is much easier to conform to the land – but also to create very great tensions between the straight and the meandering, between the flow and the node. It is this mixture of geometries which is, I think, most satisfying when you experience towns. There is no better demonstration of this dynamic than Venice: the Grand Canal and so on. Even though most buildings are very regular, they often occupy positions that are very irregular when you look from the air. And that irregularity allows adaptation to the geographic and climatic conditions much more easily than does the gridiron plan.

In this differentiation between vernacular and classical, the classical is reserved for very important buildings, which are for the whole community or for the whole town or for the whole nation, creating a hierarchy of expression and locations – in contrast with the more simple, more laconic nature of the vernacular. For instance, in this form of vernacular geometry, you can have very modest architecture without being boring. It’s always very interesting. Whereas when you have Euclidean geometries and gridiron plans, you must have much better, more ambitious architecture in order for it all to be bearable. Nothing is more boring than barracks architecture. So it’s the mixture of these two geometries and the correct placing of the hierarchy of buildings going from private or individual to public and more common-use which are the tools we use to order a great town. I applied it even to Washington DC: flooding the Tiber Creek creates a big lake, and Americans do not have to go to Venice on their honeymoon – they can come to Washington.

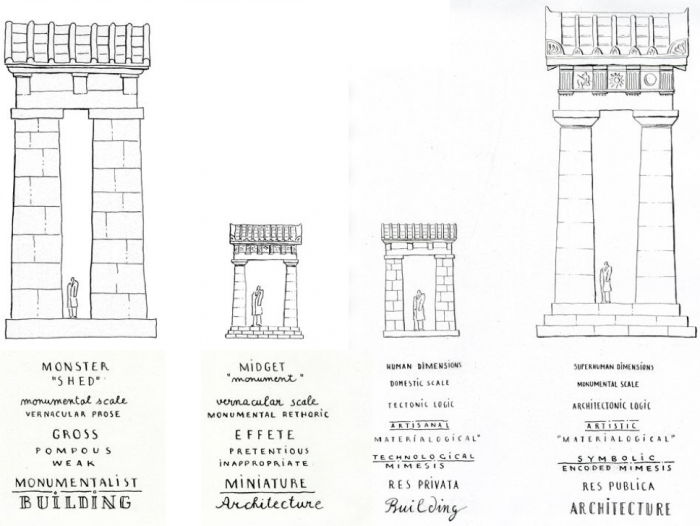

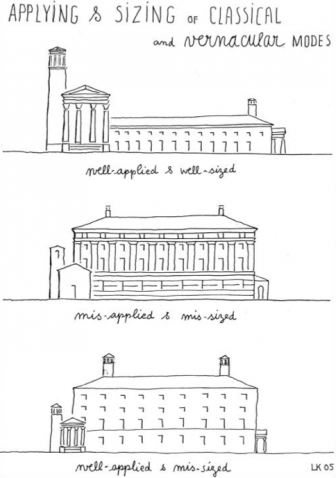

In architecture, it is a well-accepted idea that vernacular is pure technology of building. But it is not pure technology in an abstract sense; it is human technology impregnated by the size and the strength and the capacities of the human body, just as musical instruments are designed for the human hand or for the mouth or for the ear. It is the translation of this simple, purely technical performance into an art form that is what we call classical architecture. And you have it in all different cultures which have developed architecture. But in modernism this distinction doesn’t happen: there is no distinction between concert hall architecture and house architecture. It’s just that one is big and one is small. The Villa Savoir, a charming building of Le Corbusier which measures twenty by twenty-two meters, becomes the Royal Festival Hall in London, which measures fifty by seventy meters. Same number of elements, same architecture. Yet it’s by enlarging size that you change also meaning in nature. Galileo wrote pages on the fact that you cannot design a horse that is a hundred meters tall: it will collapse under the laws of gravity. It is this appropriateness of size, scale, and character which I think marks and limits architecture and gives it shape.

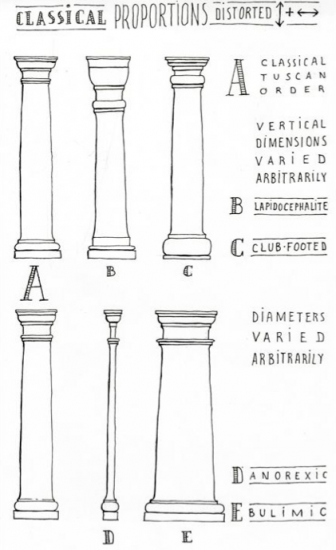

I was struck by the tuning of a piano or a violin. You first overstretch the cord or string, and then release it until it comes to the right vibration, until the tone is harmonized. I do this with my students. They have to take precise measurements of a column, or a vase or a car, and then they have to manipulate those measurements in order to understand why something is classical and to understand that that is a live value, a living designation.

For instance, you take a classical column – Tuscan, the most simple Doric kind – then you vary diameters. Keep the same number of elements, the same moldings, but make it much narrower or much wider, arbitrarily. The result can be called the anorexic or the bulimic column. Or change the vertical proportions. By making slight changes you can powerfully change the column’s character. It goes from elegant to heavy, from martial to enchanting. Or use the same elements but misplace them; it becomes a-tectonic. The logic of form and construction is disrupted if you do not assemble it in the correct way.

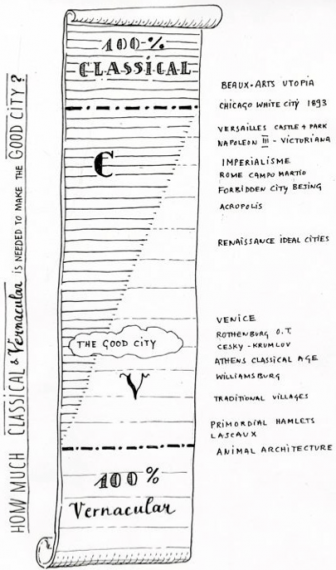

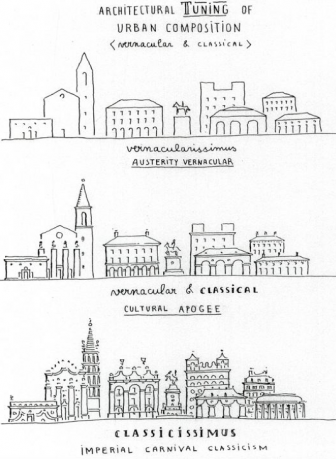

If the vernacular and the classical languages are such a very strong reality of the historic and the transcendental experiences of architecture, is it the same with music? You cannot have an allegretto that lasts for twenty-five hours. You would go crazy. These variations of tone, of rhythm, of timbre, of quality are limited, but it is actually their contrast which creates music. So how much classicism do you need to be a happy person? That’s really the question. How much classicism do you need to build a beautiful town. It doesn’t need to be all classical. You need a very large dose of vernacular. You cannot have cream every day.

A kind of ideal of classicism was performed by Burnham and his colleagues for the White City in Chicago. It was an extraordinary creation, but it was not a model of how the world could be. It was an ideal, Worlds Fair kind of world.

Another extreme of classicism would be the Beaux Arts utopia, where everything is beautiful – even the toilet seat is decorated with pearls. But it’s unsustainable in a psychological and an aesthetic sense.

And at the opposite end of the spectrum you have animal architecture, which is without any meaning beyond its own self. It’s just a pile of material that performs a certain utility. It has also its own beauty, because whatever we do over a long period of time we can only stand it and it can only survive if we cultivate beauty. Even the most solid building cannot survive for very long if it is too ugly. It just becomes unbearable. It will be blown up and destroyed. So it’s beauty which gives a building a quality that is absolutely necessary for its survival. But I think it’s the mixture of these two qualities of classicism and vernacular which gives a town or a landscape its lasting quality. In Venice, or in Williamsburg, for instance, you will find this kind of mixture of classical and vernacular.

Today, following the categorical confusion which modernism brought about and which was largely unconscious, there is no intelligent theory of modernism. We read Le Corbusier – and I love Le Corbusier, despite his problems – because he was a great writer and poet, but his work is childish. There is no serious theory there, no rational theory of how to build the world. It’s unsustainable.

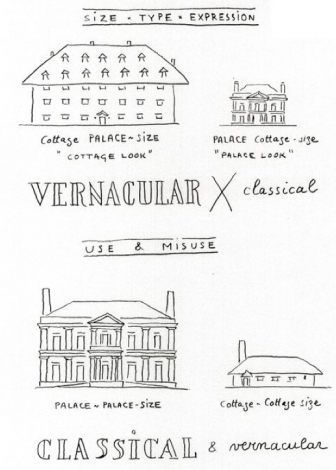

This now being the predominant set of ideas, often the industry continues anyway with the traditional models of vernacular and classical, but when they do they always get it wrong in scale or expression or size. There is a reason why very large common buildings need to be more elaborate than houses: because when you have a simple barn blown up a hundred times it becomes extremely brutal in shape. You need something more to make it not only symbolically more important but also more readable. Classical architecture is that set of forms which allows greatest readability of elements at a distance, imparts permanence, and also creates symbolic value and beauty at a scale which would not be inherent in common building forms.

Today we are faced with strange vernacular temples, hotels that imitate cottage but are the size of an aircraft carrier. Or we have little palaces – cottage size, but obviously ridiculous in scale. When you have relatively small settlements – and let’s put this in the context of music, as in the simple song with the single voice – it can go on for, say, four minutes. But if you have a single voice carrying on for twenty-five hours, you’ll get bored. To orchestrate five hours like Wagner does, you need a lot of art and it needs to be very well modulated to be bearable. I lived in a small village where there was no architecture for sixteen years. There were just three columns inside the church – just enough to have walls, openings, some tiles on the roof, and divided window panes. But art is not missing when this is placed in a beautiful landscape. The landscape takes care of the art. But in large cities you need a much richer language. In the nineteenth-century, this led to the proliferation of imperial carnival classicism – crazy buildings which become such an extraordinary performance. The education required to achieve this performance becomes tyrannical and leads to complete rejection. The Beaux Arts movement trained people until 1958, and then it was finished because, even though it was collegial education, it was also very tyrannical. The same tyranny has descended upon scientists and engineering students – it’s extremely gruesome. Doctors have to study for ten years – absolutely horrendous – day and night. Why this revolt did not happen in medical education or engineering is a mystery to me. Why just in architecture?

The best formula is this mixture of classicism and modernism, where just a few public buildings have a bit more than vernacular. And that can make very charming environments. We understand it by contrast. A building four hundred meters high topped by a statue of Lenin nearly a hundred meters high is public imperialism. The private is reduced to nothingness. On the other hand, we have private imperialism. Think of Fifth Avenue and, of course, St. Patrick’s Cathedral. It is quite a nice building, but it’s utterly meaningless among the giants of Fifth Avenue. It is completely humiliated in that setting. The properly structured, classical city is much more balanced.

I limit general building fabric to a very simple theory. Despite the fact that we have motorized vehicles, and even if we have unlimited fossil fuel, no problems with technology, and equipment galore, we should still practice traditional architecture and planning because they are imbued with a humane and aesthetic scale, which is really important.

And I identify nine ways of ordering towns and placing buildings. By arranging architecture on one side and urbanism on the other, you have between them nine modes, or combinations, by which to do it. There is a lot of choice, depending on the landscape and so on. What is perfectly unbearable as a generalized proposition is the combination of classical geometry and vernacular architecture. We generally call it “barracks architecture” and it is perfectly unacceptable. It’s fine for barracks and factories, but not for common habitat. So you have these two possibilities of geometry in combination; and then what is an absolute necessity is to have, within towns and within walkable distance, mixed used and mixed scale, which naturally leads also to mixed architecture.

But mixed use is not an absolute guarantee of a fine city, because you can create a single building containing all uses – and this was Corbusier’s idea: to have a landliner where you have the church and the factory, the public offices and the art gallery, and the housing and everything all in one building. But that is not a city; it’s a building. Buildings are not cities and cities should not be buildings. A large city is not a large house.

You have another deviation when you have uniform volumes, independent of use – where the businesses, the houses, the public offices, the temple, and the library are all contained within the same uniform volumes, controlled by a cornice line and disciplined so they become completely uniform. That’s equally nonsensical. Then you have “anything goes” mixed use. Even though mixed use is a necessity, it’s not a sufficient condition for a meaningful town.

Now, the distribution of vernacular and classical: if our home is the size of a monastery, the housing is a monumental mosque and the church is a tiny, little, dog house. You can call that well-applied but mis-sized architecture and vernacular. You can also misapply classical architecture to the utilitarian building and the church becomes just a naked box. By analyzing small or large buildings according to these principles, you are able to value whether a building is correctly structured, correctly scaled, or semantically – in the sense of meaning – correct. Only once you have a correct composition can you have a beautiful building. Otherwise it is just illusion, confusion, and deconstruction.

I think that the most important book written about energy was Kunstler’s book, The Long Emergency. And I think it is absolutely necessary to read that book. What it teaches us is that the oil peak is not going to be a symmetrical figure. It rise will rise to its peak and then there will be abrupt, very brutal change – in which we already find ourselves – leading to extreme wars and extreme violence, perpetrated to maintain our dominance in that field and in order to run our pack of instruments and maintain our mode of life. Curiously and interestingly, this peak corresponds to the nadir of the traditional arch, which used to dominate.

Modernism was very interesting when it was an experimental art, when just a few rich clients would build their interesting houses. It has become absolutely lethal as a scheme for mass building – a toxic investment. And it’s going to disappear with the increased cost of energy. It’s the fossil fuel economy that really has changed our mode of managing the air, time, energy, and land, and it is going to change. We have to prepare for that because otherwise it will erupt over our heads.

What dominated traditional architecture was climate and soil, and these conditions created very different architecture between regions. For instance, the architecture of the Basque hillsides and that of the Landes region, which is just twenty kilometers away, are very, very different. Meanwhile, the architecture of the Basque hillsides is virtually the same as that in the Himalayan Mountains because they have similar climatic conditions. It is really climate and altitude which have a very strong influence on the shape and style of buildings, historically and traditionally.

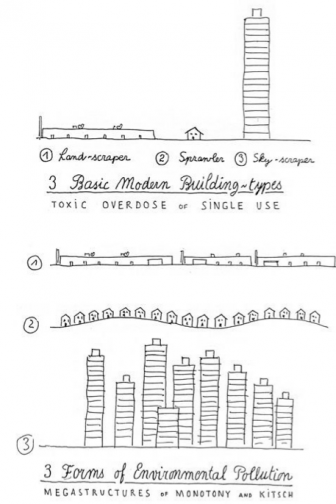

When you have a lot of fossil fuel energy you can build the same building in any climate and any altitude, but it will have no permanence because the energy it will take to maintain these buildings will be too expensive. There is only one model to counter the hubris of scale we now achieve, this excess of verticality or horizontality – and they are related problems: suburbanism piled high or suburbanism spread thin. Three dominant building types – the skyscraper, the sprawler, and the landscraper – always occur in excessively large, single-use zones.

Such zones reach beyond the limits of human scale, following the Charter of Athens which we might also apply to gastronomic intake in something like this way: instead of twenty-one varied meals each week, we have all the liquids on Monday, all the meats on Tuesday, all the fats on Wednesday, pasta on Thursday, Friday (for Catholics) fish, all the alcoholic drinks on Saturday, and the baked goods on Sunday. Then after one week the individual is dead. This is what we have been applying to cities. Housing is not the same as houses. To misunderstand that leads to the deconstruction of settlement. It’s inhuman because it has nothing to do with human settlement. And it’s not sustainable.

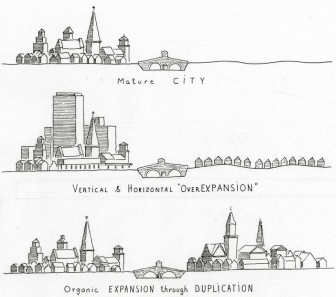

This incredible, extraordinary repetition represents the deconstruction of the landscape of human beings. We must reconstruct our overgrown cities because exceeding their proper size, as overgrowing the specific size of a cell, is disease – is cancer. This is what is happening to cities. It is as if families grew, instead of by multiplying the number of individuals, by growing the bodies of the parents until they far exceed their natural size; and this is what has happened to cities that have over-expanded, sprawled horizontally or sprawled vertically.

It is the excess, the cul-de-sac reality, which creates planned congestion. Enormous skyscrapers are vertical cul-de-sacs, which congest the network on which they sit. Why there are not more opponents of skyscrapers I do not understand, because they are completely unreasonable. Imagine skyscrapers developing not just for a generation but for 500 years. Let’s say we have no limit to fossil fuel. It would be absolutely unbearable, except living on top, to be in such a compound. It is idiotic, a completely silly idea, and it’s toxic investment. It’s destroying the future of humankind.

This extraordinary jump of scale, which you have independent of ideology, could be represented as Medieval economy, Renaissance economy, and the economy of the nineteenth century. Most utilitarian states already have enormous lots – lots taken just for housing that would be the size of three traditional towns. These enormous lots are often given to a single architect with a single function, which leads necessarily to boring architecture, and boring architecture is unbearable. So architects invent interesting forms to make the boring program more lively, and hence there are things sticking out and leaning over – this silly ballade, which is no music, it’s terrible boredom and meaningless.

Even if we had no limits to energies we should still go back to traditional plotting – in Poundbury, after all, we have the Prince of Wales as a single large landowner, but we have lots which are very different sizes, allowing very different forms of use and therefore also of architecture. Poundbury developed as polycentric instead of having a polynuclear nature. If you have enormous concentrations, this also leads to extraordinarily and extremely rigid social stratification. It is social zoning. For instance, in Colombia you have zones according to income – something like nine categories of income. You cannot buy a house if you are from one class in a zone of a different class. But it is differentiation of scale – great variety of scale, mixed scales, mixed use, mixed architecture – that leads to a rich and varied traditional architecture environment.

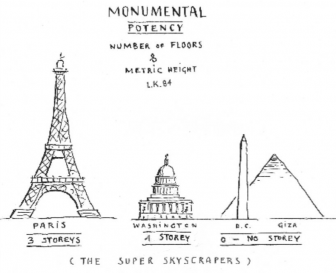

The buildings at Poundbury are now as good as any historic buildings in England. We limit our heights not metrically but by numbers. I think that a good scale for towns is three floors: what you can walk every day ten times without getting bored. Anything higher is a stress. I lived in Madrid on the eighth floor, walking up it twice every day in order to keep in shape – but it’s hell walking eight floors. So imagine even the slightest irregularity in the use of energy; when electricity is no longer assured high buildings will become extremely difficult to use.

But this limitation to three stories is no limitation to height. We are not against high buildings per se. The Eiffel Tower is a three-story skyscraper. The Capitol in Washington is a one-story skyscraper. The Washington Memorial is 150 meters high; it has no story. So you can build very high, symbolically powerful buildings, without having many stories.

Going back to small scale operations, we only use small builders, with a maximum of twenty employees. In that way you bring back and you encourage small scale, local craftsmen – those who can actually live where they work. And this redevelopment of crafts allows you to use forms which you are not able to use – a richness and an authenticity of elements which you are not able to use – with large forms of industrial building.

The project in Guatemala called Cayala is now having a lot of success. It took eight years to get it off the ground, but we had very good architects who are our main partners there and who were trained at Notre Dame University in Indiana. We now have this new generation of talent that has been properly trained. In music, you are lucky because you still have the old craft of playing instruments the proper way being taught. In architecture, we don’t have that. We have one school in the United State which teaches the craft of designing traditional buildings, and unfortunately often the industry is not able to follow. But every one of these sites is a teaching instrument.

Many architects think that imitating traditional forms is not creative, but nobody can reinvent the roof or the window. It is a complex in itself. You don’t need to reinvent the window. It has been invented. All these reinventions are just noise. The problem we have to deal with is that the industry is often reproducing traditional models, but their replacements are all fake and therefore one of the toxic results – maybe the most important toxic result of modernism is that traditional architecture has become a product of scandalous inauthenticity. The market actually buys the worst kitsch. People get fake houses. They spend their life’s earnings to get a fake house, which after twenty years is just rotting, as you well know. So every building site is reeducation of the industry.

Conservation: I know architects who have spent their lives restoring beautiful, historic buildings. They never get a prize; there is no glory. There is now one prize in this country, the Driehaus Prize, which finally recognizes the quality of people who do the right thing. You can get the world star by doing something like this – I drew this long ago and now it’s built: the army museum in Dresden looks like that. There’s no word for it but idiotic, because there’s no value in it.

Now people are so illiterate that they cannot distinguish architecture anymore. When a good restoration is done properly, they think it’s historic but not inventive. But to do a proper restoration now is an unbelievable effort of invention, conviction, education, and persistence – over months and years – to get it right. Otherwise it’s just full of mistakes.

Consider the Euro bank notes: I counted on the seven or eight bank notes eighteen mistakes of architecture. Imagine that many mistakes in some official government document. The perpetrator would be locked up. But the people who drew these, they are are scot free. It’s comical.

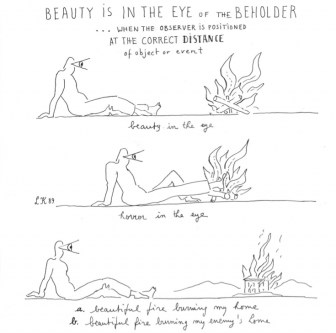

Beauty, it is said, is in the eye of the beholder. True, but the eye has to be in a certain position, otherwise beauty cannot be in it. A man can admire the beauty of a fire, but if his feet are in it, his eye will be filled with horror. To him there is no more beauty in the fire. Everything in nature, including whatever we do, is beautiful. Even the worst sound is beautiful if we have the right distance from it. Conversely, you can play the loveliest music you want, but if you are a kilometer away from it, it’s meaningless – it’s just noise in the distance. The distance, the height, and the relationship to the beholder need to be correct. That is where modernism fails on all scales. And that is what we are trying to rectify.