What a treat it is for a group of amateur string players, busy in their everyday lives, to spend a week in a far-off place and inundate themselves in practice and education concerning a single piece of music and its composer – the sort of exercise usually reserved for professionals.

Beethoven wrote his E-flat Major Quartet (Op. 74), known as the “Harp,†in 1809, just after he finished the Sixth Symphony and at about the same time that he wrote the Emperor Piano Concerto. String quartets were considered, together with piano concertos and symphonies, to be the peak of musical creativity, and Beethoven was already in the highest strata of quartet composers. He had broken out of the Haydn-Mozart mold, after finishing the last of the six Op. 18s, with his three Op. 59s. The next, Op. 74, was viewed as even more avant-garde than the 59s, and while he was busily putting on the finishing touches, the French were shelling Vienna, and soon afterwards Napoleon occupied the city. Beethoven thought that a good thing.

Those were just a few of the things about Beethoven and his tenth quartet discussed in a week-long amateur symposium and sort of master class that I attended in January in Krakow, Poland. Between time spent learning the history and structure of the work, we spent many hours in coaching sessions with exquisite musicians. What do amateurs – all fairly serious ones, but also people who make their living outside of the music world – glean from such a week, inundated in the particulars of one piece of music and its composer?

First is appreciation for the vast amount of thought and work that it takes to produce such a piece – to compose it, to play it competently, and to listen to it played the way Beethoven very probably had in mind when he wrote it. Second is to learn about how the composer conceived of the piece, to the extent that anybody knows, and the sequence of events in Beethoven’s life that led to that point in his 39th year when he composed it. And third is, rather than to play a work the way most amateurs do, to really understand the piece and its structure in light of what Beethoven was trying to convey.

The organizers of the event and its coaches were members of the Manhattan String Quartet, all highly professional and accomplished musicians, and all people who were not only fun and interesting to spend a week with but who also performed the quartet for us in a wonderful 18th century palace. Jan Swafford, author of Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (which I read on the plane on the way to Poland), was with us for much of the week as was David Clampitt, professor in the music department at Ohio State; their lectures added a great dimension to the week.

Why Poland – where Beethoven never set foot?

Krakow is the cultural and intellectual center of Poland, considered to be the most important city, historically, in Central Europe. It remains an unspoiled medieval treasure, home to Poland’s largest and most prestigious university, great museums, a stunning castle high on a hill above the old city, and a medieval cathedral where Bishop Karol Józef Wojtyła presided before he was named Pope John Paul II in 1978. The Germans seized Krakow in 1939 as they roared through Poland on their way to Russia and made it their headquarters while they occupied Poland until the end of World War II. As the Allies started bombing Berlin in 1940, German scholars determined that it would be wise to move valuable treasures – paintings, sculptures, manuscripts, old books, and so on – out of Berlin to a place where they would be far from the fires that ultimately consumed most of the city. So they crated up tons of these treasures and moved them to, among other places, churches in small towns in Poland where they would be safe. At the end of the war, as Poland sunk into the Communist East Bloc and the Poles realized that the Communist leaders would likely pilfer the manuscripts if they were found, they moved over 500 wooden crates to the Jagiellonian University library in Krakow, where they remained secretly hidden for nearly fifty years.

When they were finally made public the Germans demanded that they be returned. No way, said the Poles. You brought them here and they are now ours to keep. So there they stayed.

Musicologists were astounded to find the original manuscripts of Beethoven’s Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Symphonies, and several of his quartets along with Mozart’s Magic Flute, the Marriage of Figaro, and Cosi fan tutti, several symphonies and works by Bach, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, Schubert, and others.

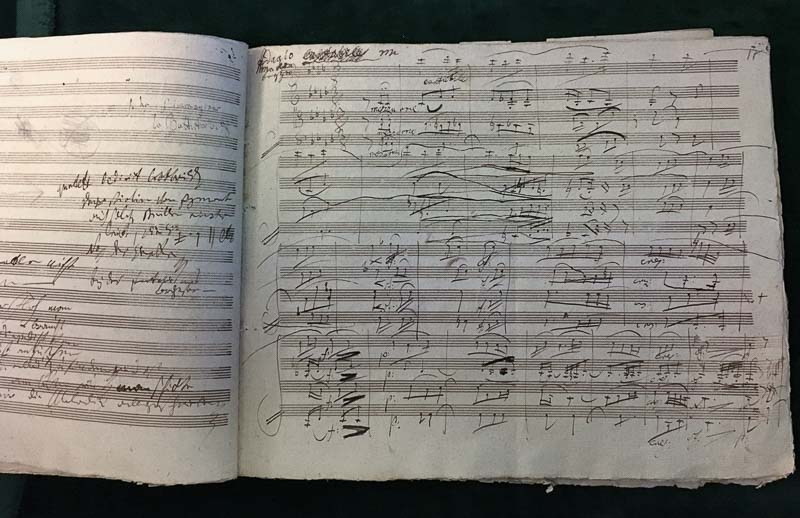

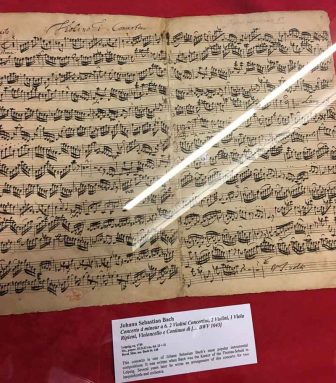

There was also the manuscript for Beethoven’s “Harp†Quartet, which we examined (very closely), astounded that the scribbles that originated the piece could actually be this beautiful quartet, and at the evidence that Beethoven agonized over his creations – particularly as the manuscript was juxtaposed with one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s most famous pieces, which looked like it was whipped off in an hour or so.

Krakow is a long way away (and below zero in January) but what a treat it was, and what an education.